Roots in the Garden of California’s Bohemia Will Be Celebrated Sunday

If walls really could talk, the hand-built stone castle just off the Avenue 43 exit in Highland Park of the Pasadena Freeway would be the mother lode of California bohemian history.

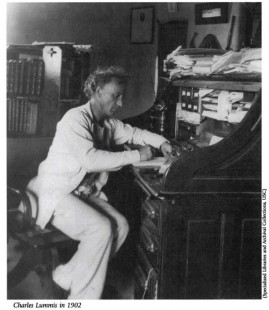

Charles Fletcher Lummis, L.A.’s “renaissance man” from the turn of the last century, began building El Alisal in 1897. Later, he liked to throw soirees on Saturday nights there among the sycamores on the Arroyo Seco. That is the memory people will try to recreate at El Alisal and along the arroyo when artists, poets, musicians and dancers celebrate “Charles Lummis Day” on Sunday, June 5.

Although Lummis wrote many books and articles in a variety of fields from archeology to librarianship, he was always more of a catalyst, helping provide a richer intellectual life to a town that might otherwise be thought of as a cultural desert.

A pompous man, Lummis was given over to elaborate costumes. Underneath his corduroys he wore a great wide red sash in the old Californio style, sandals or moccasins, a sombrero or else a leather-banded cowboy Stetson, a red cravat, Navajo jewelry and almost always the big, pompous gold medal the King of Spain had granted him for his work in glamorizing the Spanish presence in old California. He was, some have said, an elaborate poseur. But as a poseur, he was the genuine article.

El Alisal is an unusual structure of huge wood beams – rail ties from the Santa Fe and thick hand-crafted doors (the front door weighs a ton). Lummis built one of the grand doors to the dining room by modeling it on a Velasquez painting of an old Spanish caste. The house has 14-inch-thick, rock and concrete walls.

Would Lummis qualify as a bohemian? Many, if not most, of the bohemians had some sort of intellectual commitment to socialism; most likely Lummis did not. After all, he worked for Gen. Harrison Gray Otis, the publisher of the Los Angeles Times and one of the most notorious Robber Barons of the era. Still, Lummis’s love of the pastoral side of life, his love of literature, of arts and ideas would put him in good bohemian company.

In 1906, the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 drove Ina Coolbrith from that city. She had been the librarian in Oakland, just across the bay from San Francisco. Lummis was at that point the city’s first librarian. He asked her to join his staff, but she declined.

Coolbrith had the distinction not only of having been close to Mark Twain and Bret Harte in her youth – in fact, she was involved in a love triangle with them – but having also been written about as the most fondly portrayed librarian in history in Jack London’s autobiographical Martin Eden.

London gave her credit for having introduced him, a child of the slums, to the exalted world of books and ideas. The 1906 fire was a particular tragedy in Coolbrith’s life – it destroyed a just-completed manuscript she had written on San Francisco’s bohemian scene, dwelling in particular on Twain and Harte in the 1860s, and the flourishing of the San Francisco bohemia in the early years of the city.

A lot of what I learned about Lummis, who died in 1927, came from visiting Dudley Gordon. Gordon retired as professor emeritus at Los Angeles City College in 1963 and died 19 years later. Gordon was smitten with Lummis as a boy growing up back east. He arrived in Los Angeles just a few months after Lummis died

I asked Gordon to show me the corduroy coat he was famous for wearing when giving lectures on Lummis. It was Lummis’s coat – given to Gordon by a Lummis daughter-in-law in the forties. Gordon donned the suit, and we went on talking.

Gordon probably knew more about the old man than Lummis himself. Gordon admitted that he felt some identity coming from Lummis when he donned the coat. He casually observed that he knew for a fact that Lummis wasn’t as big as he said he was, for the suit fit him perfectly, and Dudley Gordon by his own reckoning was five feet, four inches tall. An admirer in Spain, where Lummis had a larger readership than in his own country, had sent the corduroy material to Lummis. It’s a unique, wide-wale, heavyweight, olive green corduroy. Gordon’s book about Lummis is entitled, appropriately enough, Crusader in Corduroy.

Gordon pointed out that some of Jack London’s earliest short stories were published by Lummis in his magazine originally called Land of Sunshine and then renamed Out West, which he edited for 14 years beginning in 1894.

Lummis was also the reason that many of the California missions were saved, including the venerable San Fernando Mission built in 1779. Lummis took a great many photographs of the Southwest – some of the most evocative are those of the San Fernando Mission, in ruins when he first photographed it. It was a once great structure looking forlorn and abandoned, crumbling into oblivion. He used the photographs in his campaign to save the remains of the mission. He was also instrumental in the recreation of Olvera Street near the site of the original pueblo in downtown Los Angeles.

Out West was his power base. President Theodore Roosevelt said it was the only magazine that he took time to read. Roosevelt no doubt was more attracted by the conservationist message of the magazine than by its bohemian aspects.

Lummis would chase London whenever he was in town, figuring that because he was the first editor to publish him, London owed him. In 1905, Lummis asked London for help in forming a Los Angeles chapter of the American Institute of Archaeology, which was carrying on preservation work – photographing the remnants of Indian and Spanish civilization in the Southwest and recording old Californio-period songs on Edison wax cylinders. London declined, not from a “lack of interest in your cause, but because of too great interest in my own Cause, which is the Socialist Revolution. Believe me,” London wrote, “this takes all my time, to the exclusion of other and minor interests.” To which Lummis countered. “We can hardly compare the relative importance of causes; but the work of the Southwest Society has this peculiarity; unless this work is done right away, it can never be done.”

London replied: “You and I are both fighters, and single-purposed fighters, too. So I am sure you will understand my position. If I have ten dollars a year to spare, I’d as soon put it into my fight than your fight. Besides, you can get capitalists to contribute to your fight, but I’m damned if we can get capitalists to contribute to my fight. I’m willing to give my countenance to your fight, but not my time or money.”

Most bohemians had revolutionary sentiments, but others like Lummis or Ambrose Bierce were essentially conservative. Whatever their politics, bohemians shared a love of travel, especially travel by foot.

Lummis had already done his share of wandering when he arrived in town.

In his trek across the continent from Cincinnati to Los Angeles, he says he fought off badmen and wild animals, and even setting his own arm after breaking it. These adventures and more are told in A Tramp Across the Continent . Dudley Gordon dismissed the notion Lummis had made up the adventures he told in that book. Gordon said there was too much hard evidence behind Lummis’ tale.

Lummis continued his adventures even after he settled in the pueblo. At 30, after suffering a stroke, he went to recover by living with the Indians in the pueblos on the Rio Grande, then he was off to archaeological digs in Peru and Bolivia. Perhaps his most amazing archaeological achievement, besides founding the Southwest Museum which is visible from the kitchen window at El Alisal, was to photograph the Penitentes – the strange, neo-Catholic crucifixion cults in the outback of New Mexico, who had rarely been observed.

There is perhaps something else that California bohemians share inordinately – a love for nature. Gordon pointed out that when he spoke before at a Sierra Club meeting, he was surprised that they were surprised that Lummis had been a close friend of John Muir, the great hero of the Sierra Club movement.

One of Lummis’ most telling romantic entanglements was toward the end of both of their lives in the early ’20s.

Coolbrith. to her great chagrin, was one of Mormon leader Joseph Smith’s many nieces. Smith had founded San Bernardino as a second Salt Lake City in the 1880s, but Coolbrith had arrived by covered wagon in Los Angeles nearly three decades before.

The town in which Coolbrith arrived had hardly five thousand souls of whom maybe a hundred were gringos. She attended the first class in the pueblo’s first public schoolhouse at Second and Spring streets in the eighteen fifties. She was not only the belle of the town during those years – she was its leading literary light – and the Los Angeles Star published her verse regularly and claimed she had an international reputation because one of the San Francisco papers had published her.

Among other activities she had led a grand march at a dance on the arm of California’s last Mexican governor, Don Pio Pico. She was much sought out by the young men, finally marrying a successful young businessman, the owner of the Salamander Iron Works, who also was a part-time minstrel trouper. The husband was dashing and romantic and insanely jealous. Once he arrived home from a show in San Francisco, bursting in on his wife and her mother and calling Ina a whore. He accused her of having affairs with just about everyone in the pueblo, which probably was a bit of an exaggeration. The husband found the kitchen knife and scissors that Ina and her mother had hidden. Dragging Ina toward him, he threatened to kill her, but nothing worse happened that day.

The next day, he returned with a six-shooter. Luckily for Ina and her mother, a gentleman passed by, telling the husband that “this was behavior unbecoming.” Even after soldiers arrived, the husband went on shouting extreme accusations. Finally, he took a wild shot at her but was stopped by a bullet from Ina’s stepfather, who had been standing nearby. The shot found its mark, for the husband’s hand had to be amputated.

Affected by messy divorce proceedings, and possibly the death of a baby, as well as devastating rains in December of 1861, Ina decided to leave Los Angeles.

But in her last years, she sought out Lummis. There are pictures of the two and obviously they are both deeply involved in a nostalgic, romantic mood, the most committed of lovers, bound together by the tides of history.

This occurred in 1925, shortly before they both died. Coolbrith offhandedly asked Lummis to write her a Spanish love story. This he did. She sent Lummis a birthday poem in 1923. Two years later, both met for what they knew would probably be their last time together. He sang Spanish songs to her, their eyes sparkled, and she rushed from the room crying.

*

Lionel Rolfe is the author of “Literary L.A.,” available on Amazon’s Kindlestore, where the subject of Lummis and many other things are fully considered. A documentary about Rolfe, his book and many other things is due for release in 2012. Visit

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Literary-LA/115509071864686?sk=wall .