Honey walks in Black Diamond Regional Park

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste.)

The East Bay’s relentless march of urban sprawl — the vast numbers of identical houses with similar lawns now decorated with fake orangey spider webs and fake tombstones, without stores or schools within walking distance, everything a drive somewhere, stoked by the freeway system, financed by taxpayers to enrich developers, climate destroying — is startlingly interrupted by its parks.

The suburban tracts gather at one end up against Mount Diablo State Park.

For years, I took my grandson about a mile or two into the park always explaining the nastiness that happens if he were to touch poison oak. When I was a freshman at university, I sat in poison oak in Tilden Park. I spent three days in the university hospital. I once walked through poison oak cut back by a homeowner so that only its bare branches were exposed. I looked as if I had changed my ethnic identity: I looked like an obese person of Chinese descent four hours after cutting myself on a branch. I teach poison oak identification to all children I come across. Total strangers. It doesn’t matter. They have to learn that and what to do when a rattlesnake rattles at you and what to do when a skunk lifts its hind legs in your direction or your dog’s direction. Usually, it’s in your dog’s direction. Dogs can do the same stupid thing thousands of times without tiring of it.

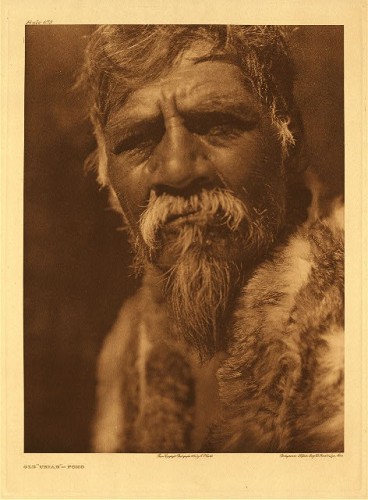

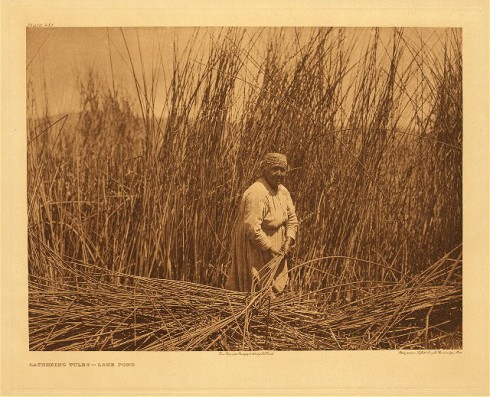

You can see Mount Diablo from most places in the Bay area. The early Spanish occupiers called it Cerro Alto de los Bolbones (High Point of the Volvon). The Volvon were one of the Bay Miwok people. The Spanish sent these Indians to the San Jose and San Francisco missions, although enough remained of them into the early twentieth century to be captured in photographs in volume 14 of Edward S. Curtis’s Indians of North America.

Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis's 'The North American Indian': the Photographic Images, 2001. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/curthome.html

Salvio Pachecho’s rancho took its name from the mountain, and the rancho extended all the way to the San Francisco Bay. One small street in downtown Concord is called Pacheco. Another is called Salvio.

Ethan and I found a 1865 cemetery at the end of a cul de sac that Pacheco donated to the Americans Vandals knocked down many of the monuments, but one remains with the name Pacheco. Now indistinguishable from all the other tracts, the adjacent houses have very quiet neighbors. Most of them died 100 years ago, although a Clayton descendant is buried there. He died in 1980. His grandfather Joel Clayton built the town of Clayton, which is where miners in the coalmines came to visit the brothel, drink whiskey, and have a hot bath. The Atchinson stage coach brought people up from Concord, which had been Salvio Pacheco’s town called Todos Los Santos.

Not too long ago, the residents of the cemetery, if they rise from their graves, say, at Halloween, looked down at miles and miles of wheat land. H. H. Bancroft, who donated the Bancroft library, had vacation property not far away. Argonauts bought up land and created orchards, many of them nut orchards, but they also grew plums, pears and peaches.

August 31st was a blue moon night, so we joined a Sierra Club-Greenbelt Alliance hike at dusk and gently examined tiny frogs in a dried pond. We waited for a male tarantula to emerge from its burrow for mating season. He will be about ten years old and will live about a year and a half more. If he finds a receptive female, he deposits his semen and moves swiftly away. Males sometimes become meals for the female. I didn’t see any tarantula. We waited a long time. I don’t know that I wanted to see one, anyway.

I drove up to the summit a week ago. From the top, you can see Clayton, Concord, the yellow hills of the Black Diamond Regional Park, Antioch, Pittsburgh, and long sloping terraces of land covered in wild wheat – the European kind, brought in the dung of imported animals, which extinguished the native grasses and replaced them. The range of mountains extends to the Alta Monte Pass in the south. To see all of this – 360 degrees of this — is like what it must be like to be in a science fiction film of life on another planet because there are no habitations for miles. If it were not for the cell towers with the suction cup things on the side, the land would look very like how it looked when it emerged from the sea.

This Saturday, I drove out to Antioch and joined a different Sierra Club group to climb in the hills of the Black Diamond Regional Park. These undulating hills are the backdrop to everything in Concord. They look soft and tawny like camels. It’s only the ubiquitous wild wheat brought to California in the dung of domesticated animals. The trees include the Coulter pine, the California Buckeye, oaks, and madrone. These are all wonderful trees. The Coulter pine slants and has enormous cones. The bark of the madrone can be smooth as if sculpted, and its bark is the color of hennaed hair and sometimes the trees arch naturally to form a tunnel. The oaks are sometimes majestic, huge, with muscular trunks and branches. The Buckeye seeds are poisonous unless they are cooked so the Indians didn’t often eat them unless they had nothing else. Many tribes mashed them and threw them into quiet pools to stupefy the fish. The Pomo people used the seeds to make a poultice for snakebite. In early spring this tree looks like it’s decorated with candles but it has no leaves left by August.

Gold brought Americans – and others – to California, but the state (1850) needed energy. A lot of the energy that the Bay area in the 1860s up to about 1900 came from the Black Diamond mines. Five towns grew up around the mines: Nortonville, Somersville, Stewartsville, West Hartley and Judsonville. The towns are gone. Park management returned a few structures that had been moved into Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, California is a few miles away.) to the hills – a big barn, a few houses that look like the houses in the film How Green is My Family, about Welsh coalminers, except the movie was shot in the mountains about Malibu.

Some of the mines are open. At the bottom levels, methane gas rises. The first miners brought canaries in cages to alert them to the methane. Coal mines always contain methane. It is explosive.

The miners who died, the babies that died, the children who lived to be a year old, those who lived into their sixties, they remain in the Rose Cemetery, but the towns are gone. The earth mostly healed.

Sarah Norton was the midwife for the coal towns and Clayton. Clayton is now an upscale community but then it was where miners went for whores, whiskey and a hot bath. On October 1879, she sped in her horse and buggy across the hills to reach a woman in Clayton about to give birth. The horse bolted and they went over the side of a cliff. The story is her apparition appears. She is the “White Witch” of Nortonville, a woman who scorned the church.

A guest of the leader sat on the wall of her grave and sang two old Welsh songs for us. The wind picked up.