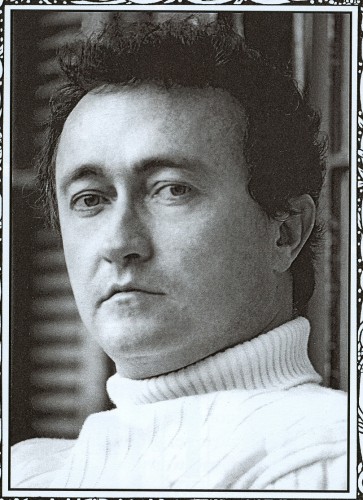

Our Friend Curtis Harrington

A Young Curtis

By Jon Zelazny

Curtis Harrington was born in Los Angeles in 1926. He made short films as a teenager, graduated from USC, and began his Hollywood career in the 1950’s. By the end of the decade, he was directing: independent films, studio pictures, made-for-TV movies, and episodic TV. He completed his last short film in 2002, and died in 2007 at the age of 80.

I knew Curtis well in his final years, as did writer-producer Dennis Bartok, the former head programmer of L.A.’s famed American Cinematheque.

DENNIS: I think the most interesting aspect of Curtis’s career is that he was really the only filmmaker to successfully transition from the avant-garde scene of the late 1940’s to directing Hollywood feature films. And when you see how distinctive his movies are, you wish he could’ve made more… but when you consider that none of them ever did much at the box office, it’s really a miracle he got to make as many as he did. I don’t remember when I first met him, because he was an ever-present fixture at American Cinematheque screenings. The only film of his I knew at that point was WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH HELEN? (1971).

Written by Henry Farrell, best known for WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE? (1962), HELEN is another psychodrama about two older women sharing a house in Hollywood. Debbie Reynolds plays a flaky dance instructor; Shelley Winters is a frumpy religious nut slowly losing her grip.

I saw it on TV when I was growing up, and it really freaked me out. The bizarre relationship between Reynolds and Winters, and the scenes of all those stage mothers trying to mold their little girls into the next Shirley Temple. I think it’s one of the great, skewed, deranged portraits of the underbelly of the movie industry.

JON: Curtis always regarded it as his best feature.

DENNIS: And it’s got Agnes Moorehead as that Aimee Semple McPherson-inspired evangelist. Curtis loved the history of Los Angeles, and all the great periphery characters here. He never saw the real Sister Aimee preach, but his parents went to her temple in Echo Park once, and he remembered them describing how every pew had a clothesline strung up over it at about eye level. They couldn’t figure it out… until Sister Aimee exhorted from the pulpit, “I don’t want to hear the clink of coins, just the rustle of dollar bills!” You were supposed to clothespin your offering to the line, and the ushers would reel it in. Curtis just cackled in delight when he told that story.

JON: A vivid childhood memory he shared with me was after we saw Robert Towne’s ASK THE DUST (2006), which depicted the 1933 Long Beach earthquake. Curtis was only seven or eight at the time, but he very clearly recalled being in the kitchen with his mother when everything started shaking. They lived just off Santa Monica Boulevard, across from what was then the back of the Fox lot; now the Century City mall.

DENNIS: Another detail from that time—which he thought should be revived—was “crying rooms” at movie theaters, where mothers could take their babies and watch the movie. I wrote down what he said about the Los Angeles Theater downtown: “My parents would drop me off there when they went to the movies. I must have been about three or four. They had a sandbox in the downstairs playroom, and a slide for the children.” Maybe that’s where his love affair with the movies began; as a little boy seeing that movie theater as a palace of wonders.

After HELEN, I think his most successful film from end to end is NIGHT TIDE (1961), which is about as close to a perfect first feature as you can get. It has the poetry and the beautiful, yearning energy of youth.

In his first starring role, Dennis Hopper plays a good-hearted Navy sailor who falls for a girl who works as a mermaid in a sideshow attraction… who slowly draws him into the beguiling web of her mysterious past.

Jean-Pierre Melville once described BOB LE FLAMBEUR as “a love letter to a Paris that no longer exists,” and I think NIGHT TIDE captures that kind of nostalgia for the old Venice-Santa Monica beach culture. I love the wonderful, slightly overexposed black and white photography; it has a very French New Wave look. I think NIGHT TIDE and HELEN were very personal evocations of what Curtis remembered from his youth.

JON: NIGHT TIDE was the first one I saw. Curtis presented it one night at the County Museum in 2000. I’d just written a screenplay that included a character based on the L.A. occultist Marjorie Cameron… whom Curtis knew, and cast in NIGHT TIDE. So I introduced myself afterwards, we chatted about Cameron, and he said, “Well, you must come to tea some time!” So I went to his house maybe a week later and he indeed served a very proper English tea in the library. It was like stepping into a Vincent Price movie.

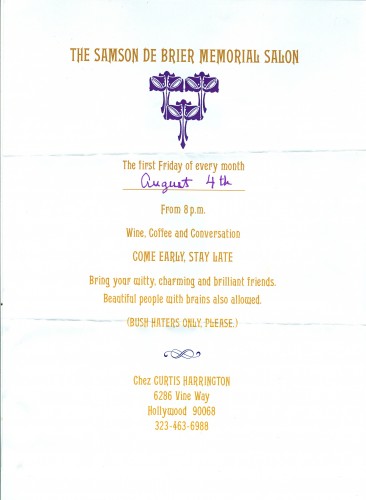

DENNIS: That house was such an expression of who he was, I wish it could have been preserved as a museum… of his soul, and his artistic sensibilities. All that great bric-a-brac: props from his movies, fin de siecle and Beaux-Arts painting and statues. Ibex skulls… 18th century prints of vampire bats… his Phrenology head… the trompe l’oiel molding around the ceilings… and that gorgeous mirror when you walked in. That whole supernatural aesthetic was very reminiscent of directors like Mario Bava and Georges Franju and James Whale. And I think all the parties Curtis hosted there were as close as I’ve ever been to a genuine bohemian salon. You read about these great social scenes, like Paris in the 1920’s, and at Curtis’s house you really did meet all sorts of wonderfully crazy people.

JON: I always had nice talks with film preservationist Robert Gitt and film scholar Tony Slide… but yeah, there were some kooks. I think Curtis—like Andy Warhol—just loved to surround himself with interesting people. One time we brought my nice, Lutheran in-laws from Florida, and they politely listened to people talk about shooting heroin and having sex with aliens.

DENNIS: I always enjoyed seeing cinematographer Gary Graver and his wife Jillian; Gary shot Orson Welles’ final films. The critic David Del Valle… horror queen Barbara Steele… and there was always some artist or writer just in from New York who Curtis would be introducing around.

JON: Anyway, after that first tea, he and I would get together for lunch or dinner and a movie every couple months. And I started seeing more and more of his work. I think my favorite of his early shorts is FRAGMENT OF SEEKING (1946).

Curtis wrote, directed, and starred in this sixteen-minute surrealistic dream story set in and around his USC dormitory. The film was hailed as a major avant-garde achievement.

I usually find it embarrassing to sit through student films, but I was amazed at what a natural director he was; the camerawork and editing already has this ineffable grace and rhythm to it.

DENNIS: The quality I most admire in almost all of his movies is the poetry. They’re all tremendously lyrical.

JON: Remember the sequence where Curtis is charging down that series of hallways in pursuit of the mysterious figure, and every time he rounds a corner, he just misses the specter disappearing around the next corner? I asked him if that was a nod to Buster Keaton’s similar sequence in THE NAVIGATOR (1924), and he thought that was hilarious. He said no one had ever compared him to Buster Keaton before.

He also showed me THE WORMWOOD STAR (1955) at his house. That was his seven-minute study of Cameron and her paintings.

DENNIS: I think we screened it at the Cinematheque once. It’s in color, right?

JON: Yeah, he shot it on Kodachrome. And Cameron’s presence, her voice of doom…

Did you ever discuss the occult with him? My impression is that unlike his old friend Kenneth Anger, who genuinely subscribes to those beliefs, Curtis was always more the curious outsider looking in. I think he was fascinated by other people’s belief in black magic; particularly if they also lived lives of “artistic” decadence, like Aleister Crowley, or Cameron’s first husband, Jack Parsons.

DENNIS: I know Curtis, Cameron, and Anger were all part of that fifties Hollywood experimental underground crowd. Dennis Hopper, Anais Nin… all those people who were in Anger’s INAUGURATION OF THE PLEASURE DOME (1953). Even Curtis’s friend Jack Larson—who played squeaky-clean Jimmy Olsen in Superman on TV—did some experimental films for Warhol in the early sixties. I don’t know how long Curtis remained in touch with Anger. They were close in the forties and fifties, but I know at some point they had a huge falling out.

JON: Anger finally put a curse on him. Curtis showed me the final poison-pen letter Kenneth wrote him. It’s hard to believe the two of them ever stood on the same philosophical ground: Anger is a dark, venomous person who clearly revels in the implicit cruelty of the Crowley system of thought.

DENNIS: You were at Curtis’s funeral, right? One of the most appalling things I’ve ever seen was how Anger hijacked that service. From videotaping Curtis in his casket, getting ejected, then somehow worming his way back in, sitting in the front pew, and continually interjecting all these obnoxious rambling anecdotes during Jack Larson’s eulogy. If Curtis had actually been there somehow, he would have strangled that asshole!

JON: Larson was amazing; he didn’t let any of it throw him. Just calmly rolled with it. “That’s true, Kenneth.” “Thank you for reminding us of that, Kenneth.”

DENNIS: Anger even threw in a “promo” for his own funeral: “I’m dying of cancer! I intend to be buried here one year from today… and it’s going to be by invitation only!”

JON: Which sadly did not come to pass; he’s still out there. I imagine Cameron must have been an equally wretched human being. How could Curtis have spent so much time with her?

DENNIS: Well, every film he made was about some kind of strange obsession… obsession with obsession, obsession with death. Images of decay, and things falling into ruin: houses in ruin, hearts in ruin. I think Curtis lived in a kind of glorious ruin; his own house always had that faintly sweet scent of decay.

JON: Which is ironic, because you never met a sunnier, more charming gentleman in your life. I was always fascinated that here was this intellectual with impeccable artistic taste… yet the stories he felt most drawn to were almost exclusively in the realm of psychological horror and the macabre.

DENNIS: It’s true. He made horror films for an art house audience… who are generally not interested in horror films.

JON: And horror movie producers are typically not the most genteel people. In The American Cinema, Andrew Sarris said Curtis needed a producer like Val Lewton; someone who really connected with that “elegant” horror ideal.

DENNIS: Though I doubt Curtis aspired to be known exclusively for horror. Like most directors, I think he wanted to make successful studio movies so he could go on and tell the more eclectic stories that interested him.

JON: At least horror opened the Hollywood door for him. Studios like scary movies; there’s always a genuine need here for storytellers with the ability to shake people up… like Curtis did with GAMES (1968).

His first studio feature is a mystery about a young “decadent chic” couple (James Caan and Katherine Ross) that find they’re in over their heads when a mysterious, witch-like woman moves in with them.

DENNIS: GAMES is a really good film. Curtis wanted Marlene Dietrich to play Lisa, but Lew Wasserman at Universal said, “Nobody gives a shit about her anymore.” So they got Simone Signoret, who was coming off an Oscar, and I think Curtis was happy with her, but he really had his heart set on Dietrich. I think he at least got to meet her at some point, in Las Vegas.

JON: He went to see her cabaret act, and they hung out for a few hours after the show. I think he regarded that as one of the great nights of his life; she was certainly part of his lifelong fascination with the films of Josef von Sternberg… whom Curtis referred to as his “directorial soulmate.” I always liked that expression.

DENNIS: Curtis wrote one of the first monographs on Sternberg, which was published in the UK in the fifties. And I remember him telling me about seeing a nitrate print of a Sternberg film called THE CASE OF LENA SMITH (1929).

JON: That’s a Sternberg? I’ve never heard of it.

DENNIS: It’s a lost film… except for Curtis’s memory of it. That’s why talking with him was always amazing, because somewhere inside him those flickering images of long ago were still there. He really was a repository of all the great films he’d seen, and the stories that went with them. He was this living connection to a vanished Hollywood.

JON: Especially all the great directors he befriended. Just off the top of my head, there was Sternberg, James Whale, Fritz Lang, and Rouben Mamoulian. Hitchcock, Welles, Kubrick. Alexander Mackendrick, Michael Powell, Lindsay Anderson. And of the living greats, there was Polanski and Jonathan Demme and Bill Condon. He said David Lynch was his favorite living filmmaker, but I don’t think they ever met.

DENNIS: I believe Curtis was personally responsible for saving one of James Whale’s greatest films, THE OLD DARK HOUSE (1932). It was long considered a lost film as well, but Curtis managed to track down one last surviving lavender-tinted print…

JON: …which he found in the vault at Universal. And then he convinced James Card of The Eastman House in Rochester, NY, to mount a complete restoration.

DENNIS: Anybody who loves Whale’s FRANKENSTEIN and THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN needs to see THE OLD DARK HOUSE, because it’s really one of the great American films of the 1930’s. It’s probably my favorite Whale just because it’s so unique and unexpected; everything about it is strange and unsettling.

JON: A Whale film Curtis turned me on to was REMEMBER LAST NIGHT? (1935) It’s ostensibly a comic romp about a group of young socialites partying all night and their compounding mishaps, but there’s a palpable sense of social critique to it. You can feel Whale’s working class judgment of these spoiled, shallow people.

DENNIS: I’ll have to check it out. I don’t know the full extent of the relationship between Whale and Curtis, but Curtis did tell me that when he was doing the starving artist routine in Paris in the early fifties—and literally flat broke—he somehow connected with Whale, who wound up giving him a pretty significant chunk of money. It was enough for Curtis to pay his rent and buy food, and he was always tremendously grateful for that.

JON: Now I could never turn Curtis on to anything in return, because he’d seen everything, but I’d often mention this or that Anthony Mann film, and he’d scoff, “Anthony Mann!” …like you couldn’t imagine a bigger hack. So one day I lent him a tape of THE FURIES (1950), and he called me a few days later to say how much he loved it… and he never sneered at Mann again! I think that was my only contribution to his body of knowledge.

DENNIS: I don’t think a day went by when he wasn’t at a screening somewhere, whether it was the Cinematheque, or the DGA, UCLA, the Academy, the BAFTA screenings. He kept up with all the new movies, and he loved foreign films.

JON: The only time I turned down an invitation was when he wanted to see BASIC INSTINCT 2 (2006). He said, “Oh, I heard Sharon Stone is just wonderful in it!”

Speaking of batty old dames, did you see THE KILLING KIND (1974)?

DENNIS: It’s excellent. I put it in the category of PSYCHO (1960) and PEEPING TOM (1960); these character studies of creepy serial killers. John Savage is really good in it.

JON: What’s strange is how the relationship with his mother veers into the upper reaches of melodrama. It’s a natural looking film, with this operatic relationship at the heart of it.

DENNIS: I think Ann Sothern’s over-the-top character was as much of interest to Curtis as the suspense elements. He was a tremendously gifted and sympathetic director of actresses, particularly great divas of a certain age and a certain style.

JON: He told me his favorite part of directing prime time soaps like Dynasty and The Colbys during the eighties was when he got to cast actors from Hollywood’s golden age.

DENNIS: I’d like to see some of his TV episodes. They probably aren’t anything special… but I’m sure they paid well, and helped his pension.

JON: He described that phase as the end of the line in his career. That he started in features, but once he accepted his first made-for-TV movie, that was how the Industry then saw him: as a made-for-TV director. Then when he started directing TV shows, he went down another category. He regarded it as a humiliating downward trajectory.

DENNIS: I think that happened to a lot of directors from the fifties, sixties, and seventies. My friend Budd Boetticher was the same way: he directed some really good TV—including the pilot for Maverick—but he would scowl and almost go into a rage if you asked him about it. Andre de Toth, same thing. Those guys would take TV jobs when they were hurting, but they were always hoping to somehow land another feature.

JON: I asked Curtis what his worst career setback was, and he told this long, convoluted story about how he was originally supposed to direct THE OMEN (1976), but through some politics at William Morris, he lost it. He was almost in tears when he told that story. I’m sure he would have made THE OMEN at least as capably as Richard Donner; that script was director-proof… and Donner went from the bush leagues to the big time. Can you imagine how a blockbuster like that would have changed the rest of Curtis’s life?

DENNIS: He would have made at least several more studio features.

JON: I wonder… I mean, his films always looked great, and he cast interesting people and got good performances, but the biggest problem is usually the stories. The dramatic structure is weak, or they lack drive, or the motivations aren’t well thought out.

HELEN, for instance, opens with those two young Leopold and Loeb-type murderers being sent to prison, then the story shifts to their two disgraced mothers trying to make a fresh start in Hollywood. Which is an intriguing opening… except I kept wondering for the whole picture when it was going to come back to those sons. I asked Curtis if he and the writer had thought about doing that opening differently, or even cutting the prologue altogether… and Curtis’s eyes started to glaze over. I thought I’d insulted him, but as I got to know him better, and the more we talked movies, I realized he simply wasn’t interested in dissecting plots or character motivation… which surprised me because he spent his early Hollywood career in script development for producer Jerry Wald at Columbia. He worked with a lot of big writers on major films.

I think NIGHT TIDE and GAMES are two of his best films partially because both scripts were pretty heavily patterned on previous classics: NIGHT TIDE is more or less a remake of CAT PEOPLE (1942), and GAMES is essentially DIABOLIQUE (1945). I think Curtis needed an established story to work off of; it freed him up to focus his energy on the visuals and the performances.

He sort of hit this nail on the head for me the night I took him to meet German director Uli Edel, who was introducing his remake of THE RING OF THE NIEBELUNGS (2004) at the Goethe Institute. Some well-educated Germans in the audience were asking about the adaptation from the original Icelandic sagas, and Uli was going into great detail about his reasons for the various changes. Curtis finally whispered to me, “Why does he get so involved in all that? I don’t care about the story… just the style!”

When did you first see USHER (2002)?

DENNIS: I think we had the world premiere at the Cinematheque. That was a very personal film for him.

Edgar Allen Poe was Curtis’s favorite writer, and he made two short films based on “The Fall of the House of Usher,” completing the first while he was in high school. Sixty years later, he wrote, produced, directed, and starred in a new forty-minute version.

It’s not really a film that’s going to scare anybody, but it’s dark and poetic, and extremely disturbing—particularly when Curtis first appears in drag as Madeline Usher. It’s everything he wanted it to be, I think. He shot most of it right at his house.

I really liked his script THE MAN IN THE CROWD, the short film he was trying to get made when he passed away. It was an amalgamation of three or four different Poe stories.

JON: I read it too. I thought it was better than USHER: less stagy, more cinematic.

DENNIS: But he was in a tough spot there: an hour-long experimental narrative? The only people who are going to put up the money for something like that are you or your friends and family. So he approached a number of his longtime friends—all very well off people, apparently—and asked for donations, and almost all of them turned him down. He was very frustrated and disappointed by that.

One time he asked me to sit in on a meeting with some possible backers. I went and listened to these two guys, and when they left, I had to tell him I thought it was bullshit. They didn’t know anything about Curtis, or his work, and I didn’t think he’d ever get a penny out of them. Which sadly turned out to be the case.

JON: I guess his plan was that if he got MAN IN THE CROWD made, he could pair it with USHER, and hopefully find a DVD company to put them both out on one disc.

DENNIS: Which I thought was a good idea. I also suggested he put some of his early short films on it as well. None of those have ever been commercially released.

JON: Did you know his friend Oneshin Aiken made a film of MAN IN THE CROWD?

DENNIS: I’ve seen it. It’s good… though I don’t think it’s what Curtis would have done. It’s more of an homage to Curtis. The movie I made a couple years ago, TRAPPED ASHES (2006), was also inspired by Curtis. The first draft of the script was all set at a party at his house. Curtis was sort of this Joel Grey-CABARET ringmaster and host for the evening, and a quartet of supernatural stories is told by various guests… and at the end, Curtis pulls out a grimoire—a book of magic—from his bookshelf, peers into the dark space where the book was and cries, “I see things! I see wonderful things!” Then he’s sucked in and disappears with that great cackling laugh he had.

JON: Wow. Did all that make it in?

DENNIS: Unfortunately, no. It’s still an omnibus film, but I never quite figured out how to make that party idea work, so the framing story became a tram tour of a Hollywood studio backlot. The tour guide is played by the late Henry Gibson… as a kind of Curtis figure, but more sinister.

JON: Is it on DVD?

DENNIS: Yeah, Lions Gate picked it up. I always hoped Curtis could have directed a segment, but the investors didn’t go for it. We got some great directors—Ken Russell, Monte Hellman, Joe Dante—but I like to think Curtis’s spirit sort of hovers over the whole thing.

The last time I saw him was a few months before he died. We had a long, leisurely lunch at Café Med on Sunset Boulevard. He didn’t look too good towards the end of his life: dark splotches all over his face, hair going in every direction, clothes rumpled and stained… he was like the ruins of the Roman Forum, overgrown with weeds! And there we were, surrounded by all these young, beautiful Hollywood hard bodies, but what did it matter? The conversation just roamed all over movie history, and then at one point he fell silent, and finally lamented, “I have no great love. I have no one I share my life with. My work is all I have to live for.”

JON: Did he ever have anyone? I was always curious about his personal life, but didn’t broach the subject because he never did.

DENNIS: No, in all the years I knew him, he never referred to any significant other.

JON: That must have made his last years particularly difficult. Maybe a week before he died, he told me one of his friends was going to hire a housekeeper for him, and I was so relieved to hear it. He had various boarders who helped and didn’t help him over the years, but he really should have had someone with him full time.

DENNIS: I think Los Angeles has really lost something with his passing. He was this wonderful, rare, gem-like part of the fabric of the city.

JON: Looking back, all I can think is how fortunate I was that he considered me worthy of welcome into his orbit those last few years.

DENNIS: I feel the same way. There was such a tremendous generosity of spirit about him, and once you were a friend of his, you were a friend for life. And we can tell stories about him, and show pictures of his house, but unless you were there, and got to be in his presence…

Every time I drive past the turn-off at Argyle and Franklin now, part of me wants to turn the wheel, head on up Vine, knock on the door, and see if Curtis is home.