George Bernard Shaw: Can His Reputation Survive His Dark Side?

By Leslie Evans

It is with a certain sadness that I come to write this. George Bernard Shaw, through his plays, was one of my early heroes. I knew only the good of him then. More recently I have come to learn things, about his political views, that I could have known then but did not, and knowing, would have seen him differently. Learning them prompts me to want to know more about his contradictory character, to decide anew what we should think of him.

It is with a certain sadness that I come to write this. George Bernard Shaw, through his plays, was one of my early heroes. I knew only the good of him then. More recently I have come to learn things, about his political views, that I could have known then but did not, and knowing, would have seen him differently. Learning them prompts me to want to know more about his contradictory character, to decide anew what we should think of him.

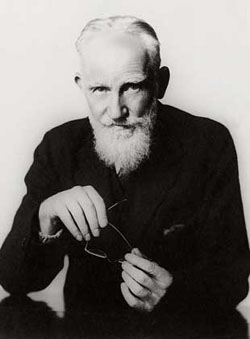

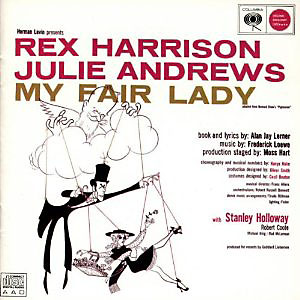

That kindly old gentleman pulling the strings attached to Henry Higgins and Eliza Doolittle on the cover of the vinyl album of My Fair Lady died in 1950 at the Methuselan age of ninety-four. Though remembered principally for his many plays, for which he won the Nobel Prize in 1925, Bernard Shaw (he hated George and didn’t use it) was also an indefatigable essayist and public speaker. An early leader of the originally tiny Fabian Society, he was a lifelong socialist, but that narrow catechism could not contain his ebullient eclecticism. Shaw was not a Marxist but a Nietzschean, not an atheist but a believer in Bergsonian vitalism.

Always an iconoclast, Shaw’s opinions, though generally on the left, ranged all over the map, were usually intended to shock, generally had a comic edge, and managed to infuriate almost everyone at some time. Unhappily, at an age when most of his contemporaries were dying off or in their dotage, beginning in his early seventies, and to the dismay of his friends on both the left and right, he lost faith in parliamentary democracy and lauded the famous dictators of the 1930s as leaders who could “get things done.” Today the American right wing has discovered Shaw’s more disreputable mouthings and found them to be a convenient club with which to beat today’s liberals and the left. The reasoning is usually along the lines of those marvelous syllogisms so beloved by the Glenn Becks of the world: Shaw liked Mussolini, Shaw was a Fabian Socialist, Fabian Socialists are similar to liberals, therefore liberals like Mussolini, Mussolini was a fascist, Hilary Clinton and Barack Obama are liberals, therefore Hilary Clinton and Barack Obama are fascists. If you think I exaggerate, take a look at National Review editor Jonah Goldberg’s book Liberal Fascism, which was #1 on the New York Times best seller list.

Always an iconoclast, Shaw’s opinions, though generally on the left, ranged all over the map, were usually intended to shock, generally had a comic edge, and managed to infuriate almost everyone at some time. Unhappily, at an age when most of his contemporaries were dying off or in their dotage, beginning in his early seventies, and to the dismay of his friends on both the left and right, he lost faith in parliamentary democracy and lauded the famous dictators of the 1930s as leaders who could “get things done.” Today the American right wing has discovered Shaw’s more disreputable mouthings and found them to be a convenient club with which to beat today’s liberals and the left. The reasoning is usually along the lines of those marvelous syllogisms so beloved by the Glenn Becks of the world: Shaw liked Mussolini, Shaw was a Fabian Socialist, Fabian Socialists are similar to liberals, therefore liberals like Mussolini, Mussolini was a fascist, Hilary Clinton and Barack Obama are liberals, therefore Hilary Clinton and Barack Obama are fascists. If you think I exaggerate, take a look at National Review editor Jonah Goldberg’s book Liberal Fascism, which was #1 on the New York Times best seller list.

Glenn Beck has an Internet post entitled Who Are the Fabian Socialists? that opens with an accurate if disturbing quote in which Shaw intones, “if you’re not producing as much as you consume or perhaps a little more, then, clearly, we cannot use the organizations of our society for the purpose of keeping you alive, because your life does not benefit us and it can’t be of very much use to yourself.”

Beck, in his usual manner, judders in an ever widening spiral of accusation, from Shaw’s distasteful declaration, to all Fabian socialists, and from there to all progressives, a category to which Shaw did not even belong, and then to Hilary Clinton, who was three years old when Shaw died, in the kind of broad-brush indictment that Jon Stewart loves to mock:

“The progressives and the Fabian socialists want to deny or distance themselves, all the while Hillary Clinton says I’m an early more than, early 20th century American progressive. That’s who George Bernard Shaw was hanging out with and they had the same elitist kind of ideas. It is where it is where the idea of eugenics, breed the perfect race, breed a better voter. So, here’s the Fabian socialists, their plan. These are just their these are just their goals and, again, there’s no Star Chamber here. These are all stated.”

This incoherent babble, whose meaning is just barely discernible, is from Beck’s own personal website. It runs from guilt by association to guilt without any association.

One liberal website was so eager to dissociate from Shaw to escape Beck’s rant they disparaged Shaw as a “eugenics-supporting lunatic,” hastily adding that “He was also an avowed socialist, which, despite Beck’s insistence to the contrary, is not the same as a progressive,” seeming to imply that eugenics-supporting lunatics are more likely to turn up among socialists than among prim progressives.

Glenn Beck may not be the best example, as he is in somewhat bad odor even among conservatives as himself a lunatic. Shaw’s excommunication, however, is fairly broad on the right. His entry on Conservapedia, the right-wing alternative to Wikipedia, provides two brief sentences listing without further elaboration the titles of five of his plays, followed by a long page devoted to Shaw’s endorsement of eugenics and his late-life praise of dictators.

If you want the worst, up front, from an unbiased source, we have Stanley Weintraub’s “GBS and the Despots” in the August 22, 2011, Times Literary Supplement. Weintraub is a distinguished Shaw scholar, and editor of Bernard Shaw: The Diaries 1885–1897.

In 1927 Shaw published in the London Daily News a letter titled “Bernard Shaw on Mussolini: A Defence.” He came under sharp attack for this by both socialists and liberals, but persisted in his admiration of Mussolini throughout the 1930s. While sharply condemning Hitler’s anti-Semitism, he spoke positively about the Nazis for renouncing the Versailles Treaty, which Shaw had opposed, and for their supposed economic reforms, writing in 1935, “The Nazi movement is in many respects one which has my warmest sympathy.” As late as 1944, deep into World War II, when he was strongly supporting the British war effort against Germany, he still in print had something positive to say about Hitler’s Mein Kampf. He claimed that he was a National Socialist before Hitler was.

He was well-disposed toward Oswald Mosley, Britain’s home-grown fascist demagogue, declaring Mosley “the only striking personality in British politics.” He turned against the German Nazis and Italian fascists during World War II, but never wavered from his adulation for the Soviet Union, first under Lenin, and then, undiminished, under Stalin.

As it happens, George Orwell in his 1946 pamphlet James Burnham and the Managerial Revolution does shed light on the Glenn Beckish claim that Shaw’s dual embrace of communism and fascism was broadly typical of Fabians or other sorts of socialists:

“English writers who consider Communism and Fascism to be the same thing invariably hold that both are monstrous evils which must be fought to the death; on the other hand, any Englishman who believes Communism and Fascism to be opposites will feel that he ought to side with one or the other. The only exception I am able to think of is Bernard Shaw, who, for some years at any rate, declared Communism and Fascism to be much the same thing, and was in favour of both of them.”

Shaw also made extreme and indefensible statements about euthanasia. Glenn Beck doesn’t even quote the worst, such as a 1933 suggestion that chemists develop a “humane” poison gas for the extermination of those he regarded as social parasites, those who refuse to work and insist that society support them (including the idle rich as well as the deliberately idle poor).

Reactionary columnist Jonah Goldberg in his risible book Liberal Fascism, a 467 page tome written apparently because some lefty called him a fascist, and amounting to a “Nyah, nyah, you’re the fascist!”, spills four or five pages of vitriol on “liberal heroes” who “shared Shaw’s enthusiasm” for eugenics. What is dishonest about all this stuff is not the quotes from leftists but the claim that eugenics was widely supported by leftists and the omission of all those on the right who were eager, and very well-funded, champions of eugenics – for some, poison gas and all.

The problem with the right-wing use of Shaw to pillory moderate socialists and nonsocialist liberal progressives is not only that very few of the latter held such views, but that this kind of cherry picking is ahistorical. It doesn’t seek to understand how such now unacceptable opinions gained currency, or who held them and why. It is what Pascal Bruckner calls the sin of anachronism, which he contrasts to real history, which “forbids us to judge preceding centuries from the point of view of the present.” Sympathy for Italian fascism, and even German Nazism, was widespread after the bloody debacle of World War I and the Great Depression, and far more so on the right than on the left, Shaw being an outlier here.

The very idea that there is such a thing as social change dates mainly from the Industrial Revolution, when it became obvious in daily life. Much of philosophy, social theorizing, and political organizing since has aimed to figure out to what degree we can have effective input into our own future, to guide the unfolding changes rather than simply submit to them. Many paths forward have been embraced only to prove disastrous later. Communism and fascism are the textbook examples. Darwin showed that there was biological change as well as political and economic change. Eugenics was an attempt to take charge of human evolution, which was ultimately found to be far more difficult and to involve a far greater potential for evil than its first advocates imagined.

Eugenics was generally thought of as a harmless way to take an active part in improving the “race.” One of its main projects was simply to legalize and popularize birth control. That gave it a “progressive” tinge. But it was quickly harnessed to Social Darwinism and began to be invoked to bar immigration of Asians and other “undesirables,” which was more popular on the right, along with some trade unions. It expanded in the United States to bar marriage or reproduction by those deemed mentally unfit, a category that began with the retarded and the mentally ill, and which expanded to swallow up many poor black women. These atrocious policies were widely enacted into American law through the lobbying of major foundations, which were generally more conservative than liberal.

Eugenics was supported by some leftists and liberals, such as H. G. Wells, John Maynard Keynes, Margaret Sanger, Sidney Webb, Virginia Woolf, progressive Republican Theodore Roosevelt, and Stanford University President David Starr Jordan. But similar advocacy was widespread on the right and center, where eugenics champions included, in Great Britain and Ireland, Conservative Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, Winston Churchill, W. B. Yeats, T. S. Eliot, D. H. Lawrence, and Julian Huxley; in the United States, Alexander Graham Bell, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, John Harvey Kellogg (founder of the breakfast cereal company), and Clarence Gamble (heir to the Proctor and Gamble fortune). The main difference is that the Irish and Britons mainly talked about eugenics while the American corporate foundations poured large amounts of money into its implementation. In the U.S., thirty states adopted involuntary sterilization laws used to forcibly neuter 64,000 people between 1907 and 1963.

This was promoted by wealthy organizations such as the Rockefeller, Ford, and Carnegie foundations. The Rockefeller Institute prominently employed the pro-Nazi French biologist Alexis Carrel, who wrote:

“Those who have murdered, robbed while armed with automatic pistol or machine gun, kidnapped children, despoiled the poor of their savings, misled the public in important matters, should be humanely and economically disposed of in small euthanasic institutions supplied with proper gasses. A similar treatment could be advantageously applied to the insane, guilty of criminal acts.” Notice how the criteria becomes more and more sweeping as the list grows, from murderers to armed robbers to mere swindlers and then to people who spread false information, and finally the mentally ill who step over some legal line.

The most prominent organizer of the eugenics movement in the United States was the apolitical zoologist and geneticist Charles B. Davenport (1866-1944), who headed the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, which was funded by the Carnegie Institute. Davenport’s eugenics creed included the proviso, “I believe in such a selection of immigrants as shall not tend to adulterate our national germ plasm with socially unfit traits.”

Notably the Conservapedia does not mention the association with eugenics of any of the conservatives. It does recount the state laws requiring sterilization of the “unfit,” but sanitizes its account by referring to the whole movement as “radical” and omitting all but the Carnegie foundation and Davenport from its summary.

Exterminationist ideas of the sort Shaw voiced in the 1930s were then, as they still are today, more common than we like to recognize, and not particularly linked to eugenics. In the early twentieth century colonialism and empire were more often the springboard. On the left it was H. G. Wells, not Shaw, who talked about exterminating “inferior” races. On the right, novelist D. H. Lawrence said such things. The British conservative author George Chatterton Hill in his 1907 Heredity and Selection in Sociology wrote that “Nothing can be more unscientific, nothing shows a deeper ignorance of the elementary laws of social evolution, than the absurd agitations, peculiar to the British race, against the elimination of inferior races.” The British “race,” he said, “by reason of its genius for expansion, must necessarily eliminate the inferior races which stand in its way. Every superior race in history has done the same, and was obliged to do it.”

American diplomat and international lawyer Henry C. Morris in his History of Colonization (1900) insisted that if the native population of a colony could not be induced to produce a profit for the colonialists, “the natives must then be exterminated or reduced to such numbers as to be readily controlled.” The Illinois Institute of Technology

Chicago-Kent College of Law to this day sponsors the Henry C. Morris Lecture in International and Comparative Law.

It is not clear even that Shaw’s few comments about euthanizing the congenitally antisocial and those who refuse to work were connected to his support for eugenics. He doesn’t say that the antisocial are biologically inferior, which would be the eugenics argument. The quotations usually circulated or cited here are a fairly close paraphrase of Saint Paul’s Second Epistle to the Thessalonians, 1:10: “For even when we were with you, this we commanded you, that if any would not work, neither should he

eat.” Shaw most likely picked the idea up from Lenin’s State and Revolution, where it appears as “He who does not work shall not eat.” The saint and the revolutionary don’t spell out that the culprits will die, but generally not eating has that result. Yet, Shaw gives the premise a cruel activist twist that goes beyond his sources.

Of course, today loose exterminationist talk has, from overuse, lost much of its shock value. Its proponents only have to avoid the trigger word “poison gas.” Right-wing radio talk host Michael Savage, with an audience of eight to ten million for his nationally syndicated show, The Savage Nation, in a July 21, 2006, broadcast on Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad ‘s pending appearance at the United Nations urged, “I don’t know why we don’t use a bunker-buster bomb when he comes to the U.N. and just

take him out with everyone in there.”

Shaw’s accuser, Glenn Beck, when asked about Iran, was superlative in his bloodlust: “I say we nuke the bastards. . . . In fact, it doesn’t have to be Iran, it can be everywhere, anyplace that disagrees with me.” (Premiere Radio Networks, The Glenn Beck Program, May 11, 2006).

Shaw is useful to the right as one of the extremely few well-known socialists who also said some positive things about fascism. He fits into the current bizarre campaign to rewrite history and fob off fascism as a left-wing movement. This is in part merely a cynical attempt to unload on the opposition the crimes of one’s own ancestors. But in part it is sheer ignorance of history. Many of today’s Tea Party enthusiasts, when judging some snippet they read or hear about the past, decide who was left and who was right by

consulting their own private convictions and seeing if they match. They seem blithely innocent of any notion of the history of ideas and take as a given that their own recently acquired small-government panacea has always been the hallmark of conservative thought.

Liberals from the eighteenth through the early twentieth century were champions of capitalism, political democracy, free elections, human rights, and religious tolerance. Conservatives were supporters of the absolute monarchies, established religions, aristocracy, and strict social hierarchy. Obviously there have been shifts since, and there were always individual thinkers who broke the pattern, but conservatives through the end of World War II were more likely to be in favor of strong central governments than

liberals, except on the issue of social welfare measures such as the New Deal, which flowed from their disdain for the lower classes, not from their fear of big government. As recently as Reagan and Bush junior we have had conservative presidents who claimed they favored small government while greatly expanding federal power and costs.

It was the conservative parties and politicians that were the allies of Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco during their rise to power, and in Italy and Spain for the duration of fascist rule, not the liberal or left parties. The left has its own sins, in widespread illusions in Soviet Russia and the Lenin and Stalin dictatorships, but there is no grounds to foist on it

responsibility for its adversaries’ portion as well. In any case, many on the left and most liberals were opponents of Soviet communism.

The right-wing blogosphere, Glenn Beck, and the Conservapedia have a simple approach to someone like Bernard Shaw, apart from their attempt to use him to smear today’s liberals: brand him as irremediably wicked and excommunicate him from polite society. The difficulty is that many significant figures in our history have these kinds of dark sides to them, and the typology is far from following any clear left-right cleavage.

The problem with deciding what we should think of Bernard Shaw is the problem of historical context. Judged by the standards of our own day, many of the outspoken figures of our past have inexcusable blemishes. Yet to cast them all out would leave us without a history or a culture. Churchill admired Mussolini, approved of colonialism, opposed Indian independence till the end, and was a staunch eugenicist. Kipling was an anti-Semite. Yeats supported the Blueshirts, the Irish fascist organization. Brecht, Langston

Hughes, Charlie Chaplin, Dashiell Hammet, and Frida Kahlo were Stalinists, and far from the only ones. Henry Ford promoted the anti-Semitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Mahatma Gandhi supported white apartheid in South Africa. Chaucer, Martin Luther, William Shakespeare, Immanuel Kant, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Karl Marx, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (the founder of French socialism), H. L. Mencken, Mark Twain, Joseph Kennedy (father of JFK), G. K. Chesterton, and T. S. Eliot all said some pretty awful things about Jews. Abraham Lincoln, despite the Emancipation Proclamation, was a racist. Even Jesus, when approached by a Canaanite woman asking him to heal her daughter, first refuses, saying “I am not sent but unto the lost sheep of the house of Israel,” and calls the non-Jews “dogs.” (Matthew,

15:22-26)

Everyone must make their own judgment on whether a political or literary figure of the past was so inexcusably far from an acceptable moral standard as to write them out of the historical canon. I am not prepared to give up Yeats or Kipling, Churchill or Gandhi. I am not so forgiving of Henry Ford, the profascist poet Ezra Pound, or Brecht. I still listen to Wagner, but cannot silence the small voice recalling that Nietzsche broke with him over Wagner’s anti-Semitism, or that his music was played over the loudspeakers at Auschwitz.

If all I knew about Bernard Shaw was what I read on Conservapedia there would be no reason to refrain from burning his books, or at least encouraging libraries to discard them. But that is not how it was. In a certain sense I grew up with Shaw’s plays. Somewhere I had seen the 1938 film of Pygmalion with Wendy Hiller and Leslie Howard, for whom I was named. My family were Republicans, but my mother (who after I left home became a liberal Democrat) was an avid follower of television drama, and Shaw was

frequently on the bill in the fifties. Particularly memorable was a production of The Devil’s Disciple in November 1955, when I was thirteen. Shaw’s only play set in America, at the time of the American Revolution, it starred Ralph Bellamy, one of my favorite actors, as Pastor Anderson, and Maurice Evans as the clever and heretical Dick Dudgeon. Thought to be a useless wastrel, Dudgeon acts with matchless heroism when, while visiting the minister’s home, he is mistaken for Pastor Anderson by General Burgoyne’s soldiers, who have come to arrest Anderson to be executed as a hostage. Dudgeon lets himself be mistaken for the pastor to save the other’s life.

The following spring there was Caesar and Cleopatra, with lots of clever dialogue between Cedric Hardwicke and Claire Bloom. Then came My Fair Lady. My mother took my sister and me to a rare outing, the 1957 West Coast touring company of the new musical, with Brian Aherne and Anne Rogers in the roles premiered by Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews. We bought the original cast LP, which my sister and I played until we knew every song by heart.

I was innocent yet of politics and caught only a whiff of the class divisions Shaw was satirizing. And it would be decades more before I could see something in Henry Higgins of Vandeleur Lee, the charismatic singing teacher and choral conductor who shared the Shaw home when Bernard Shaw was a child, phonetics substituted for voice instruction. But my true fascination with Shaw came a year later yet, and this time it was focused directly on the playwright and his ideas.

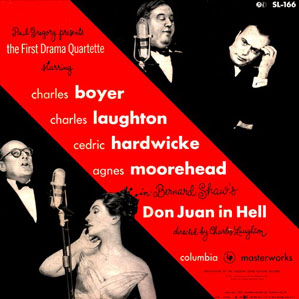

Noel Swerdlow, a high school friend with advanced views, one day took me to Wallach’s Music City in Hollywood, where he insisted that I buy the First Drama Quartet LPs of their reading of Don Juan in Hell, the lengthy dream sequence from Shaw’s 1903 play Man and Superman. The cast was beyond superb: Charles Laughton as the Devil, Charles Boyer as Don Juan, Agnes Moorehead as Donna Ana, and Sir Cedric Hardwicke as the Statue. The LPs are long gone but you can still download the MP3 version from Amazon at a minimal cost.

Noel Swerdlow, a high school friend with advanced views, one day took me to Wallach’s Music City in Hollywood, where he insisted that I buy the First Drama Quartet LPs of their reading of Don Juan in Hell, the lengthy dream sequence from Shaw’s 1903 play Man and Superman. The cast was beyond superb: Charles Laughton as the Devil, Charles Boyer as Don Juan, Agnes Moorehead as Donna Ana, and Sir Cedric Hardwicke as the Statue. The LPs are long gone but you can still download the MP3 version from Amazon at a minimal cost.

In Shaw’s rendering of the Don Juan legend the story picks up after the living statue, Donna Ana’s father, has dragged the lothario off to hell. Here Don Juan debates the Devil on the meaning of life. Hell is not a pit of fire and brimstone but a palace of hedonism. Heaven, which remains off stage during the play, is some kind of workshop where people toil selflessly to improve humanity.

The talk – and it is all talk, no action of any kind takes place, but the play in not less gripping for that – ranges over art, music, love, human cruelty and cowardice, marriage, evolution, the Life Force, and the quest for a superior mind, the superman.

The Devil champions his realm of love, art, music, and beauty against the brutality of human life on the physical earth in one vast speech that in print is a single paragraph three pages long. Here is just the beginning of it:

“And is Man any the less destroying himself for all this boasted brain of his? Have you walked up and down upon the earth lately? I have; and I have examined Man’s wonderful inventions. And I tell you that in the arts of life man invents nothing; but in the arts of death he outdoes Nature herself, and produces by chemistry and machinery all the slaughter of plague, pestilence, and famine. The peasant I tempt today eats and drinks what was eaten and drunk by the peasants of ten thousand years ago; and the house he lives in has not altered as much in a thousand centuries as the fashion of a lady’s bonnet in a score of weeks. But when he goes out to slay, he carries a marvel of mechanism that lets loose at the touch of his finger all the hidden molecular energies, and leaves the javelin, the arrow, the blowpipe of his fathers far behind. In the arts of peace Man is a bungler. I have seen his cotton factories and the like, with machinery that a greedy dog could have invented if it had wanted money instead of food. I know his clumsy typewriters and bungling locomotives and tedious bicycles: they are toys compared to the Maxim gun, the submarine torpedo boat. There is nothing in Man’s industrial machinery but his greed and sloth: his heart is in his weapons.”

Don Juan concedes that human society is often brutal but he rejects the Devil and his proteges’ escape into a ghostly world of beauty, art, and love, the aristocratic retreat into cultivated living. The Devil tries to tempt him, saying, “Here, I repeat, you have all that you sought without anything that you shrank from.”

Don Juan rejects this:

“On the contrary, here I have everything that disappointed me without anything that I have not already tried and found wanting. I tell you that as long as I can conceive of something better than myself I cannot be easy unless I am striving to bring it into existence or clearing the way for it. That is the law of my life. This is the working within

me of Life’s incessant aspiration to higher organization, wider, deeper, intenser self-consciousness, and clearer self-understanding. It was the supremacy of this purpose that reduced love for me to the mere pleasure of a moment, art for me to the mere schooling of my faculties, religion for me to a mere excuse for laziness, since it had set up a God who looked at the world and saw that it was good, against the instinct in me that looked through my eyes at the world and saw that it could be improved.”

Read that in your head in Charles Boyer’s imperious French accent and see if you are not moved!

Naturally at sixteen I was attracted to what sounded like a life dedicated to such a higher purpose. I didn’t fail to notice Shaw’s particular take on this, that the job to be done was to aid the evolution of humanity toward the creation of the superman. I had read Thus Spake Zarathustra and grasped that this was a Nietzschean idea. But Nietzsche

himself presents the search for the superman as a lonely personal spiritual and intellectual quest, not a government program in selective breeding. In any case I didn’t feel I had to take seriously the goal of a biological superman to be inspired by the idea of a life of service to humanity in some form.

We now know some very negative things and a few positive ones about the old playwright. What else would I need to know about GBS, as he styled himself, to decide if his works are worth keeping and his life worth recalling? I turned to the fat one-volume edition of Michael Holroyd’s magisterial biography.

Shaw was born on July 26, 1856, in Dublin. His father, George Carr Shaw, was an alcoholic. He married Lucinda Elizabeth “Bessie” Gurley for her money, but her father outsmarted him and put it in a trust that wouldn’t come due for many years. It was a loveless marriage. Whatever small ability the pair had to display affection was exhausted on their two daughters. None was left for their third-born, George Bernard. When young George was around six, to make ends meet they shared a house with music impresario and voice teacher George Lee, who later called himself Vandeleur Lee. Lee was captivating and the household became a platonic menage a trois, with Lucinda Shaw far closer to the music teacher than to her useless husband. This was a pattern that GBS imitated many times in his life, in passionate but usually unconsummated

love affairs with other men’s wives.

Called Sonny as a boy, he did not get on in school but was a voracious reader, steeped in Shakespeare, Homer, Sir Walter Scott, Alexandre Dumas, Shelley, and Byron. By the time he was ten he lost his belief in religion. Through Vandeleur Lee he developed a love of music.

At fifteen he took a job as an office boy in a land firm. In June 1873, when Shaw was sixteen, Vandeleur Lee left their home in Dublin and moved to London; Shaw’s mother Bessie followed. Her two daughters went with her, leaving Sonny behind with his father. The three women in London lived separately from Lee, Bessie and her younger daughter Lucy pursuing musical training with him. Missing her, as well as the music that had been so central to the household, GBS taught himself the piano, becoming a fairly accomplished classical pianist. Early in 1876 his older sister Agnes died of a wasting disease. Shaw took the occasion of her funeral to move to London, where he lived with his mother and Lucy, though as ever on remote terms.

Vandeleur Lee had not prospered in England. He hired Shaw to ghost write music criticism for a paper called The Hornet, which was the beginning of Shaw’s first career, as a music critic. Lee unexpectedly proposed marriage, to Lucy rather than to Bessie, which led both Lucy and her mother to break all ties with him. Shaw continued the association, as writer and as piano accompanist in Lee’s voice lessons.

Shaw had a striking appearance. When grown he stood six feet two, but weighed only 140 pounds, almost a stick figure. He grew a distinctive red beard to cover scars from a bout of smallpox. When he was twenty-nine he bought his first new suit, the then distinctive if faddish Jaeger woolen set, widely promoted for its purported health benefits. It included wool underwear, a tweed coat and waistcoat, and short breeches with long stockings. This became his trademark garb, more and more unfashionable as the decades passed.

The London GBS discovered was the one described by Charles Dickens, who had died at fifty-eight in 1870, only six years before Shaw’s arrival. The city’s slums were a cesspit of squalor and wretchedness whose like can be seen today only in third world countries, though they are making a comeback in the wake of the current world recession. Horror at this human misery led Shaw to hopes of reform and, after some years, to the budding socialist movement.

In the meantime he tried to break into the literary world. Between 1879 and 1883 he wrote five novels, all of them rejected by every publisher he approached. The first, Immaturity, did not see print for fifty years. The other four were eventually serialized in two socialist periodicals, between 1884 and 1888.

Following a brief stint at the telephone company, he spent the next eight years studying at the British Museum, supported by his mother, a favor he would return when he became a successful playwright. In this period he adopted vegetarianism, in part from his reading of Darwin, which led him to see animals as fellow creatures. He also abstained from alcohol, having seen his parents’ marriage ruined by his father’s drinking.

He trained as a boxer, had his first girl friend, and, in 1882, attended a lecture by the American reformer Henry George that set him on the road to political radicalism. He soon discovered Karl Marx and ploughed through Das Capital, not yet available in English, in a French translation. In September 1884 Shaw joined the Fabian Society, which had been founded earlier that year. For the next eight years, until his first performed play, Widower’s Houses, in 1892, he devoted most of his energies to the new organization.

The Fabians were opposed to forming a socialist political party. Instead they pursued a strategy of permeation, by which they meant patiently persuading influential figures and leaders of the existing Liberal and Tory parties. They advocated a range of moderate reforms that would come to be widely accepted in Europe and North America in the century that followed: a welfare state on the model of Bismarck’s Germany, women’s suffrage, slum clearance, for a national health service, a minimum wage. Of the various English socialist groups the Fabians were the least proletarian. Their views were the soul of moderation, their members thoroughly respectable, their outlook mostly local

and provincial. It would be years before they would even discuss their position on foreign policy and British colonialism.

Shaw quickly became one of the small group’s most effective platform speakers and pamphleteers. The leadership team that would cohere for the next half century was complete with the adherence of Sidney and Beatrice Webb. Shaw was the inspired propagandist, the Webbs the statisticians and careful researchers. In the thirty years before the bloody slaughter of the Great War, the Fabians were essentially the liberal wing of the great mass of Victorian believers in the inevitability of onward and upward progress. Portions of their list of reforms were often endorsed by Tory as well as Liberal politicians.

In 1900 Shaw drafted the Fabians’ first declaration on foreign policy, “Fabianism and the Empire.” It was anything but radical, viewing empires as a progressive step beyond narrow nationalism, rating the British empire as the most worthy, and endorsing the British side in the Boer War. By the late 1880s Shaw, and the Fabians with him, had rejected Marxist class struggle. Shaw envisioned the split in society as between those who worked at something for a living and those who did not. This differed from the

Marxian class theory in that it condemned only that part of the rich who lived off rents and interest, and with them those of the lower classes who chose not to work or who chose to be criminals.

The Fabians were instrumental in founding the Labour Party, also in 1900, and became the party’s brain trust for decades afterward, many British prime ministers ranked among their growing membership.

Meanwhile Shaw was establishing himself as a book reviewer and music critic, and even as an art critic. In February 1889 he became music critic for The Star under the pseudonym Corno di Bassetto, and then switched to The World, now signing himself GBS. During these years he gave a thousand unpaid lectures for the Fabians and was much sought after as a platform speaker and teacher.

During the 1880s he had several mainly platonic affairs: with Karl Marx’s youngest daughter, Eleanor, who was living with Edward Aveling and would commit suicide when Aveling married someone else; with later-famous children’s author Edith Nesbit, married to the Tory socialist Hubert Bland; and with May Morris, William Morris’s daughter. Morris, best remembered as a central figure in the Arts and Crafts movement and the Pre-Rafaelite artists, was an early socialist leader and headed the Socialist League, a more proletarian rival to the middle-class Fabians. Shaw admired Morris but counted him “a privileged eccentric and in no way an authority as to socialist policy.” Shaw’s biographer adds that this was “almost exactly in the same manner as the Labour Party was later to regard G.B.S. himself.” May, impatient with Shaw’s reticence, married, prompting Shaw to renew the attachment, on the pattern of Vandeleur Lee with his own parents. The marriage failed, but Shaw by that time typically withdrew again.

Shaw’s one seriously consummated affair was with Jane Patterson, an older woman and close friend of his mother’s. This lasted, with some interruptions, from April 1885 until the beginning of 1893. During one of the interstices he was offered a contract of terms for living together by Annie Besant, then a Fabian firebrand but later the head of Madame Blavatsky’s occult Theosophical Society. He turned her down.

A more serious affair led to a final break with Jane Patterson and helped redirect Shaw toward his ultimate vocation. In 1890 at May Morris’s home he met and fell in love with Florence Farr. She was then at the very beginning of a career that would make her a leading figure of the English and Irish stage. Shaw saw and reviewed for the press her performance in A Sicilian Idyll by John Todhunter. This event drew together several of the major strands of Victorian Irish culture. Todhunter was a close friend of Irish

poet and playwright William Butler Yeats, and a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the occult organization in which both Yeats and Farr would become prominent. Farr would be a frequent lead in plays by both Shaw and Yeats, and through her Shaw established his own links with Yeats’ Abbey Theatre in Dublin and a long personal friendship with Yeats and his patron, Lady Gregory.

Another influence on Shaw in the period was seeing Janet Achurch in 1889 in the first English production of Ibsen’s The Doll’s House, shocking in Victorian England when Nora dares to break free from her stifling marriage. Shaw saw the play five times. He was inspired by Ibsen to see the theatre as a venue for serious ideas, at odds with the drawing-room comedies and bedroom farces that were the staple of the Victorian stage. He was inspired enough to write one of his few nonfiction books, Quintessence of Ibsenism (1891).

Then, in 1892, his first play, Widowers’ Houses, opened. It ran for only two performances. Creaky though it was, it previewed much that became typical of Shavian drama. It took stock figures of Victorian theatre but inverted their characters. The young hero, Trench, falls in love with the daughter of a wealthy man. Discovering that his prospective father-in-law is a slumlord, Trench demands that his fiancee reject any money from him. The reversal is that she refuses and breaks off the engagement. It is

discovered that Trench’s trust fund is equally tainted and the lovers reunite, accepting their unscrupulous financial foundation. Add witty dialogue and many humorous turns of phrase to coat the social problem under examination and you have a Shaw production.

His biographer, Michael Holroyd, makes a pithy summary of what distinguished his subject’s work:

“Shaw’s plays were not plays. Archer [an early collaborator] had no trouble in spotting this. His friend had dispensed with plot, with character, with drama and the red corpuscles of life, to demonstrate that argument squeezed into a well-built dramatic machine was as good as any play.”

His first three plays were not financial successes. Widowers’ Houses was followed by The Philanderer, the title suggesting the content and based loosely on some of Shaw’s own adventures in other people’s marriages, and then in 1893, Mrs. Warren’s Profession, in which Vivie Warren discovers that her genteel upbringing was financed by her mother’s brothel, with undertones of possible incest, as there is doubt about which of her mother’s several lovers is her father, and her own fiance is the son of one

of the possibles.

These plays were disturbing in their day and had a hard political message not far from the surface. Shaw resolved in future to write plays more about people and their situations, with more humor and less message. He published the three early efforts together as Plays Unpleasant. Afterward he arranged book-length collections of his further plays, setting a new pattern for play publication on both sides of the Atlantic, prefacing each play or volume with a lengthy essay on the social ill motivating the sparkling dialogue.

He followed with Arms and the Man, a romantic comedy with a feminist theme set in Bulgaria during the 1885 Serbo-Bulgarian war. This was his first well-received effort. He had written it for Florence Farr, who played Raina Petkoff, the female lead. Raina rejects her Bulgarian war hero fiance Sergius Saranoff to marry a Swiss mercenary, Captain Bluntschli, who had fought on the Serbian side. Bluntschli may have been an enemy but he at least respected her while her lout of a war hero was out with other women. In later years the play ran seven times on Broadway, and between British and American productions has had casts that included Ralph Richardson, Margaret Leighton,

Laurence Olivier, Marlon Brando, Len Cariou, Kevin Kline, Raul Julia, John Malkovich, and Helena Bonham Carter.

Having lived in poverty his first forty years, financial success came only with his eighth play, The Devil’s Disciple, which in 1897, mainly in America, earned him 2,000 pounds (about $272,000 in today’s dollars). In his long life he published no less than fifty-nine plays and was the most performed and honored playwright in the English language for several generations, second only to Shakespeare. Most of these works have not survived, but a core canon have remained staples of theatre companies in many countries: Arms and the Man, Candida, The Devil’s Disciple, The Doctor’s Dilemma, Captain Brassbound’s Conversion, Caesar and Cleopatra, Man and Superman and its dream sequence Don Juan in Hell, Major Barbara, Androcles and the Lion, Pygmalion, Heartbreak House, and The Apple Cart are all still performed on stage and for television. His most popular play was his vision of Joan of Arc, Saint Joan (1923).

The Internet Movie Database lists no fewer than 175 film and television productions of Shaw plays, in multiple languages, from a 1921 silent Czech film of his early novel Cashel Byron’s Profession to a 2009 Canadian film of Caesar and Cleopatra starring Christopher Plummer. The entries cluster between 1938 and 1985, a bit heavier in the 1950s and 1960s. On television he is well represented in the Hallmark Hall of Fame and the BBC Play of the Month.

Saint Joan was filmed by Otto Preminger in 1957 with Jean Seberg in the title role, screenplay by Graham Greene. On stage Shaw’s Joan has been played by Sybil Thorndike, Katharine Cornell, Wendy Hiller, Uta Hagen, Siobhan McKenna, Joan Plowright, Genevieve Bujold, Lynn Redgrave, Amy Irving, and Judi Dench. Unexpectedly for a man of the left, Shaw did not take the expected path of glorifying the rebel Joan and casting her interrogators and executioners as consummate imperialist and ruling class villains. In his only tragedy he insisted there were to be no villains, each side acting as their beliefs told them they must.

By 1894 GBS and Florence Farr ended their affair, her occultism grating too harshly against his Fabianism. He more and more in his writings and in his life began to elevate work above love. He formed repeated intense romantic attachments to women, usually prominent actresses, but withdrew from physical sex. His compulsorily chaste lovers included Janet Achurch, Ellen Terry, and Stella Campbell, stage stars of their day. His pattern included long walks, visits to museums, and always an extensive exchange of letters, many of them at least verbally passionate.

Then in 1898 at the age of forty-two he married for the first time. His bride was Charlotte Payne-Townshend. She was Irish, rich, six months younger than he, intelligent, and with a certain inclination toward radical politics, but plain of face and figure. And, perhaps essential to their marriage, deathly afraid of childbirth. They were happily married for forty-five years. It is said that the marriage was never physically consummated. He had lived with his mother, though not on very good terms, until their wedding. He and Charlotte in 1906 bought a house in the village of Ayot St. Lawrence in Hertfordshire, just north of Greater London. They lived there for the rest of their lives. They traveled widely together until quite late in life. After a time Shaw resumed his flirtations and heavy correspondence with other women, which Charlotte tried to ignore. He seems to have abstained from sex with them as well as with his wife, with the possible exception of a young American beauty, Molly Tompkins, who pursued him, then already seventy, during several of his prolonged visits to Italy beginning in 1926.

As the nineteenth century closed, GBS continued his work with the Fabians on a reduced level. He spent six years as a local elected London official. In the British system he served in the St. Pancras Vestry as vestryman, a member of the elected parish council, changed to a borough in 1900. Here he worked effectively and amiably with moderate and conservative members of the local government.

He updated and published his nonfiction The Perfect Wagernite in 1898. A major change was taking place in his thinking. He was inspired by the Ring cycle, but unhappy that in Wagner the heroes are liberated only after death, by ascending to heaven. He needed an earthly salvation and wanted something more than ordinary politics as the sole vehicle to achieve the egalitarian future he hoped for. He began looking for an additional ally on that road. He believed he found it in his own interpretation of evolution.

It was typical of the Victorians to embrace Darwin but miss the point of what he was saying. Darwin’s natural selection made no promise as to outcomes, only stating that successive generations of organisms favor genetic variants and mutations that advantageously adapt them to their environment. Many Victorians chose instead to read “Evolution,” as a straight road to ever greater physical and mental perfection alongside the social and political perfectability they also believed in. Most of those who championed this ideological version of evolution thought of themselves as Darwinians. Some, looking for a more definite and rapid promise of improvement, professed versions of evolution that explicitly differed from Darwin. Marx and Engels rejected natural selection, with Marx instead endorsing a little-known crank geologist who claimed to be able to predict stages of steady improvement in animal species from changes in the earth’s soils. Shaw abandoned atheism and created a creed he called Creative Evolution in which the Life Force was an immanent power driving the human race toward rapid (by geological standards) improvement in mind and self-consciousness. This Life Force was a mystical biological field of some kind, whose strength was being added to the mere human efforts of social reformers such as the Fabians. Humans and other living things were said to be endowed with a self-determining essence separate from the physics and chemistry that ordinary science recognizes.

Looking back some years later, in his preface to the five Back to Methuselah plays, published in 1921, he acknowledged that he had intended the Don Juan in Hell dream sequence in Man and Superman to be the founding document of a new religion:

“Accordingly, in 1901, I took the legend of Don Juan in its Mozartian form and made it a dramatic parable of Creative Evolution. But being then at the height of my invention and comedic talent, I decorated it too brilliantly and lavishly. I surrounded it with a comedy of which it formed only one act. . . . Also I supplied the published work with an imposing framework consisting of a preface, an appendix called The Revolutionist’s Handbook, and a final display of aphoristic fireworks. The effect was so vertiginous, apparently, that nobody noticed the new religion in the centre of the intellectual whirlpool.”

GBS was never modest, but he is right that Don Juan in Hell was perhaps his most brilliant piece of writing, new religion of selective breeding of the superman at its core notwithstanding. The critic Max Beerbohm wrote of it, “In swiftness, tenseness and lucidity of dialogue no living writer can touch the hem of Mr Shaw’s garment. In Man and Superman every phrase rings and flashes.” Beerbohm became a close friend. In a letter decades later on Shaw’s ninetieth birthday he articulated what many thought:

“My admiration for his genius has during fifty years and more been marred for me by dissent from almost any view that he holds about anything.” For Beerbohm the secret of disentangling Shaw’s extremist preaching from his plays was his odd combination of seriousness and irrepressible frivolity, the comic side that invaded all his productions.

Shaw was no scientist. He appropriated the idea of Creative Evolution from the literature of his day that could offer support to his faith in a radical improvement in humanity and eliminate the evils of his own time. In part he seems to have found what he was looking for in the French philosopher Henri Bergson, whose 1907 book Creative Evolution advocated a form of vitalism in living organisms and coined the term that Shaw officially adopted in the preface to Back to Methuselah.

A more immediate influence was the novelist Samuel Butler, best remembered as the author of The Way of All Flesh and Erewhon. Butler was also a tireless adversary of Darwin, promoting his own version of evolution. Butler’s two key differences with Darwin were that Butler wanted to claim a role for some kind of innate intelligence in directing evolutionary change from within organisms, and he wanted to resurrect Lamarck’s idea of the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Shaw at one point wrote: “What damns Darwinian Natural Selection as a creed is that it takes hope out of evolution, and substitutes a paralysing fatalism which is utterly discouraging. As Butler put it, it banishes Mind from the universe.” In a 1911 debate over religion with G. K. Chesterton, who would convert to Catholicism in 1922, Shaw staked out his own ground:

“As for my own position, I am, and always have been a mystic. I believe that the universe is being driven by a force that we might call the life-force. We are all experiments in the direction of making God. What God is doing is making himself, getting from being a mere powerless will or force. This force has implanted into our minds the ideal of God. We are not very successful attempts at God so far, but . . . there never will be a God unless we make one . . . we are the instruments through which that ideal is trying to make itself a reality.” (Cited by Holyroyd.)

Inheritance of acquired characteristics was a second arrow in the quiver for hastening evolutionary change. It proposed that building up muscles through exercise or energetic use of the brain through study, or other environmental influences on an organism could be passed on to offspring. Plainly if this were so, evolutionary change would be perceptible in a generation or two instead of the eons-long process of random genetic adaptation to particular environments. Accepting Butler’s revival of discredited Lamarckism led Shaw in the 1930s to give credence to Soviet claims about the agricultural miracles of the quack plant geneticist Trofim Lysenko, later shown to be fraudulent.

The point is not so much to show that Bernard Shaw believed things that were at variance with scientific knowledge – a great many Republicans do that – but that he was a man in a hurry to see the change he had aspired to from his early youth and was trying to enlist both supposed natural and mystical forces to bring it closer. Michael Holroyd describes Shaw’s new religion as “a moral commitment to progress thorough the Will, answering the need for optimism in someone whose observation of the world was growing more Pessimistic.” This turn toward a form of forced-hope mysticism took place in Shaw before the cataclysm of World War I, in his recoil from the more ordinary evils of poverty, injustice, inequality, and inertia of the political leaders of Victorian England. (The long-lived Victoria died only in January 1901, as GBS was formulating his response to the age to which she gave her name.) Pessimism would slowly gain the upper hand after the debacle of the war. His eventual turn toward what he thought of as strong leaders was part of the same process.

* * *

GBS wrote only one thoroughly Irish play, John Bull’s Other Island, 1904, focused on the conflict between a British land developer in Ireland and a priest who opposes him. Though the premiere was ultimately moved to London from the planned Abbey Theatre opening, over disputes on length and Shaw’s negatively realistic portrayal of his native Ireland, the episode cemented a lifelong friendship with Yeats and still more so with Lady Gregory, central figures of the Irish Literary Revival.

The world war marked the end of the long nineteenth century and with it much of the Victorians’ hopes for social improvement. Shaw was particularly shaken, as he took more seriously than most of his comrades the long-standing socialist credo of internationalism, which in the climate of feverish patriotism after August 1914 left him open to charges of being pro-German. The parties of the Socialist International had pledged before the outbreak of hostilities to refuse support to their own governments in the event

of war. They overwhelmingly turned patriotic when the artillery began to fire. A few in Britain, such as Bertrand Russell, declared themselves pacifists and went to prison. Shaw on November 14 published a long supplement to the New Statesman entitled “Common Sense About the War.” It earned him immediate obloquy.

He accused Britain’s rulers of being little better than their Prussian opponents, hypocrites who had planned war with Germany since the latter’s victory over France in 1870 and now played the innocent victim of Junker militarism. The Americans would have to come in, he said. “They will have to consider how these two incorrigibly pugnacious and inveterately snobbish peoples, who have snarled at one another for forty years with bristling hair and grinning fangs, and are now rolling over with their teeth in one another’s throats, are to be tamed into trusty watch-dogs of the peace of the world.”

He was immediately shunned as a traitor. Prime Minister Asquith’s son said he should be shot. Dramatist Henry Arthur Jones declaimed that Shaw’s mother was “the hag sedition.” In America, Theodore Roosevelt called him a “blue rumped ape.”

But he was not actually against Britain’s participation in the war. Instead he proposed, quixotically, that war aims be reconfigured along democratic and socialist lines. He demanded democratic rights for the troops, trade union representation in the army, an end to secret diplomacy, and a pledge not to take drastic reprisals against Germany at the war’s end. Finally, he agreed with the government that the German invasion of France, if not Belgium, merited Britain’s entry into the war:

“It left us quite clearly in the position of the responsible policeman of the west. There was nobody else in Europe strong enough to chain the mad dog.” And: “We must have the best army in Europe.” He quietly donated 20,000 pounds to the British War Loan, about $2.8 million in today’s dollars. The acrimony over his pamphlet was a measure

of the wave of heady war fever that swept Britain in the early days of the fighting. It would take several years for him to be forgiven. Churchill in his 1937 Great Contemporaries showed that he still bore a grudge. There were a few who took Shaw’s side. Bloomsbury author Lytton Strachey, who would later win fame for his Eminent Victorians, described Shaw as “our leading patriot.” In 1917 at the invitation of Douglas Haig, commander-in-chief of the British army, Shaw spent a week at the front in France.

He wrote only a few skits during the war, but followed afterward with several of his most successful plays: Heartbreak House in 1920, the five Back to Methuselah fantasy plays on Old Testament themes in 1922, and his triumphant Saint Joan in 1923. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1925. One newspaper dubbed him “the most famous author in the world.”

In this period he and Charlotte deepened their friendship with many prominent figures who crossed the whole political spectrum: John Galsworthy, G. K. Chesterton, Lady Gregory, Arnold Bennett, James Barrie, author of Peter Pan, and composer Edward Elgar. Of course Fabians Sidney and Beatrice Webb remained among their dearest friends. They were especially close to T. E. Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia, a frequent house guest. Shaw had provided editorial help and Charlotte served as proofreader for his The

Seven Pillars of Wisdom. She and Lawrence over the thirteen years before his death exchanged six hundred letters. Shaw added regular radio talks over the BBC to his other activities.

Shaw began his drift toward the dictators in the usual left-wing way, by imagining that the Russian Revolution of October 1917 was ushering in the egalitarian utopia he had dreamed of. A decade later he thought he saw almost comparable signs of progress in Mussolini’s corporatist state. The Fabian strategy of permeation seemed to be having meagre results. Labour was in power briefly in 1924, with Ramsay MacDonald at its head. Then MacDonald headed a second Labour government from 1929 to 1931, but, disastrously for the left, continuing as Prime Minister in August 1931 in a coalition with a Conservative and Liberal majority. MacDonald, the first Labour Prime Minister, was expelled from the party. Labour would not return to power until the end of World War II.

Where, Shaw asked, was the socialism? In part his disappointment rested in the ultamatistic concept of socialism he had been carrying around in his head since the end of 1910, when he wrote that he advocated “a state of society in which the entire income of the country is divided between all the people in exactly equal shares, without regard to their industry, their character, or any other consideration except the consideration that they are living human beings . . . that is Socialism and nothing else is Socialism.”

It would be hard to find any living socialist or even communist who would endorse this proposition. But as that is what he was looking for it would help explain his attraction to forceful extremists. He joined a large swath of the population throughout Europe that had lost faith in official parliamentary parties and their governments after the bloodbath of World War I and the prolonged economic collapse of the Great Depression.

It was the age of totalitarian fantasies. The dictatorships that came to power in Russia in 1917, in Italy in 1922, and in Germany in 1933 and their many followers shared a disdain for parliamentary democracy and personal liberty. They promised a new prosperity and security through a semi-militarized mobilization of the population and giving free rein to police agencies to suppress dissent. Millions who in the past had hankered after liberty found themselves equally willing to give up their liberty to be welcomed into the powerful national fold. These movements transcended the customary governmental limits of both left and right. The Soviet revolution of 1917 won a wide

following among workers and intellectuals in the West, while radical rightists in Italy and Germany were indisputably popular on their home ground and had large numbers of sympathizers abroad. Partisans who looked only at “left” and “right” saw these two rival currents as mortal enemies. There was an argument to be made, and it would get more of a hearing after the second world war, that they were similars. Shaw took the latter view, and as he already approved the Russian version he saw no reason to withhold at

least qualified endorsement of the other two.

In 1931, as he turned seventy-five, GBS visited the Soviet Union, accompanied by Conservative MP Lady Nancy Astor, a long-time friend and militant anti-Communist whose own views leaned more toward Hitler. He was met at the train station by Karl Radek and Anatoly Lunacharsky. Radek had been Vice-Commissar for Foreign Affairs in the early days of the Russian Revolution. A former Trotskyist, he was purged, then capitulated to Stalin in 1929, and was enjoying a brief rehabilitation when he met Shaw, before Stalin had him shot in 1939. Lunacharsky had been Commissar of Enlightenment, in charge of education and the arts, in the first Soviet government. He was already in semi disgrace and would escape the purges only by dying in 1933. His works would soon be banned in the USSR.

Shaw was given a staged tour of happy workers and peasants. He believed it all, imagining it to be Fabianism triumphant. Lady Astor was unimpressed, declaring, “I think you are all terrible.” She was applauded when her translator, no doubt deliberately, misstated her remarks. Stalin gave the pair a lengthy interview in which he succeeded in charming Shaw, who managed to miss all the brutality of the Soviet system. This trip converted him to communism.

Churchill, who always had a keen eye for such things, in his Great Contemporaries mocked GBS’s Soviet excursion:

“The Russians have always been fond of circuses and travelling shows. Since they had imprisoned, shot or starved most of their best comedians, their visitors might fill for a space a noticeable void. And here was the World’s most famous intellectual Clown and Pantaloon in one, and the charming Columbine of the capitalist pantomime. . . . Arch Commissar Stalin, ‘the man of steel’, flung open the closely guarded sanctuaries of the Kremlin, and pushing aside his morning’s budget of death warrants, and lettres de cachet, received his guests with smiles of overflowing comradeship.”

For Shaw, all of this was a matter of abstract ideas, chimeras whose content bore almost no relation to the realities of life in Stalin’s Gulag or one of the fascist states. One right-wing website today calls him a murderer. That’s absurd. Probably the worst thing he did in life was to convert the Webbs to Stalinism when he returned to England, spoiling forever their reputation, which rested on their political convictions far more than his did.

Another figure who attracted Shaw for the next few years was Oswald Mosley. In November 1932 he described Mosley as “one of the few people who is writing and thinking about real things and not about figments and phrases.”

Mosley the previous month had founded the British Union of Fascists. That he still had credit anywhere on the left might seem surprising, but not if you know his trajectory over the previous fourteen years. Scion of an aristocratic family, Mosley was a decorated veteran in World War I. He was a Conservative Member of Parliament from 1918 to 1922, when he became an Independent, then joined the Labour Party, and still later the Independent Labour Party, an older group to the left of the official Labour Party. He served as a minister in Ramsay MacDonald’s 1929 Labour government. In early 1931 he formed the New Party, with a generally Keynesian program to help the unemployed

in the Depression. After a visit to Mussolini, Mosley lurched to the right and was converted to fascism. This was still before Hitler became chancellor of Germany, whose National Socialists never called themselves fascists, and there were still widespread illusions in Italian fascism on both the right and the left.

Not seeing much motion toward communism in England, Shaw now looked to fascism as the next best thing, calling it “the only visible practical alternative to Communism.” In retrospect one would have to say that Shaw was unusual, but not alone, in his day in seeing the striking similarity in methods and governmental forms of the two dictatorial systems, the hyperstatist extremes of left and right. Both professed an extreme populist rhetoric while busily eliminating all sources of opposition, especially from

the very people they claimed to champion.

Usually their partisans could see only the differences. If anything, Italian fascism, the only one then extant, was a noticeably less repressive form of government than Leninist or Stalinist Russia, which had very large partisan support among the European working class and intelligentsia. Hitler would permanently brand fascism as consummate evil, but that would become apparent outside of Germany only as World War II approached, inflated a hundred-fold with the revelations of the Holocaust later. The fever of the totalitarian virus was coursing through the blood of Western society and had not yet run its course.

Shaw did denounce Mosley’s anti-Semitism, and within a few years lost interest in him. What had briefly attracted him was the image of a charismatic leader. That seems to be mostly what he saw in Lenin, Stalin, Mussolini, and, for a while, Hitler. When challenged by Beatrice Webb as to why he should see something positive in the rightist figures, who had “no philosophy, no notion of any kind of social organization,” he replied that it was their powerful personalities. These were men who broke through the paralyzing inertia of the parliamentary systems of their day.

Even in his late years, as misanthropy crept into his view of the human race, Shaw rejected racism and misogyny. He and Charlotte made a world tour by ship in 1933, stopping in South Africa, India, China, and the United States. The next year he published The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God (and Some Lesser Tales), where he proposed that “the next great civilization will be a black civilization,” and, as Holroyd summarizes, “that future gods may be female rather than male; and that the biological solution to the race war between black and white is intermarriage.” This, as can be imagined, created a great furor, in England almost as much as in apartheid South Africa.

In a certain way Shaw in his prolonged old age used his fancifully re-imagined dictators to threaten England: if you don’t carry out serious reforms these are the kinds of leaders who will do it for you. His plays were less widely performed in the 1930s. They were more modern sounding than Oscar Wilde but nevertheless had a certain Victorian mustiness about them. Intellectuals in particular were now looking on him as a figure out of the past. Holroyd says that The Apple Cart, finished in 1929, “was to be the last of Shaw’s plays to win a regular place in the standard repertory.” He wrote fourteen plays after that. He had begun in 1921 to prepare a collected edition of his works. The first volumes appeared in 1930. When it was finally complete the ultimate edition ran to thirty-seven volumes.

Shaw’s circle of friends in his late years expanded beyond theatre people and Fabians. He was close to world heavyweight champion boxer Gene Tunney and the Catholic Prioress of Stanbrook Abbey, Dame Laurentia McLachlan. He wrote admiringly of Einstein and Churchill, the latter returning the compliment.

In his last decades much of his thought and writing delved into fantasy and surrealism. This brought him closer to W. B. Yeats, whose work had always mined that vein. At the first meeting of the Irish Academy of Letters, in September 1932, Shaw was elected president, Yeats vice president.

He and Charlotte lived quietly at Ayot. A non-Christian, he made large contributions to the local church to repair the roof and the organ. He underwrote replacing the windows in the village school. Each year he sent the headmistress a check to pay for sweets for the children at the village shop. He received endless requests for donations, for aid, for letters of support or endorsement. He responded to many of them. One poet wrote to say his clothes had been destroyed in a fire. Shaw sent him a check for 400 pounds with a note saying how much he disliked the fellow’s poetry. One street person asked for a pair of boots. Shaw had them sent, then found that the man returned them

several times to be repaired.

A German actress wrote saying she had the perfect body and wanted to have his child so it would inherit his great brain. He responded, “What if the child inherits my body and your brains?” In a bookstore he noticed a copy of one of his books with a handwritten inscription. He bought it, packed it up, and sent it to the original dedicatee with a note, “With the author’s renewed compliments.” Invited to a party by a note saying the hostess would be “At Home” on a certain date he fired back, “So will G. Bernard Shaw.”

Years before, he had inherited a building in Ireland, which he donated to the Catholic Bishop of Kildare and Leighlin to serve as a school; it became the Technical College. Leonard Woolf described him as “personally the kindest, most friendly, most charming of men.”

After Hitler became chancellor in 1933 Shaw declared the Nazis “a mentally bankrupt party” and called for an anti-German pact between Britain, France, the United States, and the Soviet Union. He described Hitler as a new Torquemada and compared his anti-Semitism as akin to a case of rabies. These are significant qualifications on the few positive things he said about the Nazis. He still counted the Nazis as in the right in abrogating the Versailles Treaty and claimed that he was the only one in England who was still polite in writing about Hitler.

Shaw was far more sensible about the second global war than the first. He refrained from denouncing British “Junkers,” and for the first months limited himself to hopes for an early negotiated settlement. At the beginning of 1940 the BBC asked him to make a broadcast on the war. The Ministry of Information vetoed his script. Harold Nicolson, then Churchill’s official Censor, rejected the speech, saying, “Shaw’s main theme is that the only thing Hitler has done wrong is to persecute the Jews. As the Minister [Duff Cooper] remarks, millions of Americans and some other people [believe] that this is the only thing he has done right.”

Shaw came out for uncompromising war against Hitler and Mussolini. Early in 1941 he told an American reporter, “[T]here is a very dangerous madman loose in Europe who must, we think, be captured and disabled. If we are right, he is as dangerous to you as to us; so we ask you to join the hunt.”

Where he had been persona non grata during World War I, his plays experienced a major revival during the second war. There were many productions in the early years and by 1944 there were nine Shaw plays running simultaneously in London. Casts in the wartime period included Robert Donat, Vivien Leigh, John Gielgud, Edith Evans, Deborah Ker, Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, Sybil Thorndike, and Margaret Leighton. Traveling companies took his plays to rural towns, munition factories, and mining outposts.

His generation was dying off, even the long-lived ones. He had served as one of the pall bearers when Thomas Hardy, fifteen years his senior, died in January 1928. The others ranked around the coffin were James Barrie, John Galsworthy, the poet Edmund Gosse, A. E. Houseman, and Rudyard Kipling. T. E. Lawrence, thirty-two years Shaw’s junior, was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1935. Beatrice Webb, one of his closest friends since the 1880s, died in April 1943. Charlotte developed osteitis deformans, a debilitating bone disease that left her hunchbacked and unable to walk unaided. She began to hallucinate. She died that September. H. G. Wells followed in August 1946, and

finally Sidney Webb in October 1947.

For his ninetieth birthday, in 1946, the newly founded Penguin paperback publisher issued the “Shaw Million,” simultaneous publication in Britain of ten of his titles in editions of 100,000 each. The lot sold out in six weeks.

In his last years he suffered from anorexia; his weight, never much, fell to 126 pounds. On September 10, 1950, GBS fell in his garden, fracturing his thigh. He died on November 2. In his will he left art works to public galleries and theatres in Britain, Ireland, and the United States.

Before submitting the question we began with for your decision I want to call two of Shaw’s contemporaries for their views, one from the left, one from the right. First, George Orwell, who lived just half as long as GBS but whose years matched precisely the second half of Shaw’s life. Orwell was also a socialist, but unlike Shaw, one who understood better than almost anyone the horrors of totalitarianism.

Orwell seems never to have written a piece devoted solely to Shaw. His comments are scattered in essays with broader themes. He admired Shaw’s plays but not his politics. On the positive side he wrote:

“It would be an absurdity to regard Shaw as a pamphleteer and nothing more. The sense of purpose with which he always writes would get him nowhere if he were not also an artist. In illustration of this I point once again to Arms and the Man. . . . Nowhere is there a false emphasis or a clumsily contrived incident; the play gives the impression of having grown as naturally as a plant. There are not even any verbal fireworks; brilliant as the dialogue is, every word of it helps the action along. (Cited by Loraine Saunders, The Unsung Artistry of George Orwell.)

Orwell made a three-fold criticism of Shaw’s politics, grouping him with other writers who shared one or another of Shaw’s attitudes. First, that as rebels such authors failed to anticipate that if they were successful in shattering the status quo the results might be much worse rather than much better. Second, that most British authors of Shaw’s vintage were extremely provincial, which led them to magnify the evils of British society while not grasping the true scope of foreign repressive regimes toward which they were too tolerant. And finally, that those writers who embraced Soviet communism – or fascism – constituted a dangerous totalitarian current that other socialists

should be wary of.

The first criticism appears in his essay “Notes on the Way” in the British weekly Time and Tide of April 6, 1940, in the dark early days of World War II:

“[T]here was a long period during which nearly every thinking man was in some sense a rebel, and usually a quite irresponsible rebel. Literature was largely the literature of revolt or of disintegration. Gibbon, Voltaire, Rousseau, Shelley, Byron, Dickens, Stendhal, Samuel Butler, Ibsen, Zola, Flaubert, Shaw, Joyce — in one way or another they are all of them destroyers, wreckers, saboteurs. For two hundred years we had sawed and sawed and sawed at the branch we were sitting on. And in the end, much more suddenly than anyone had foreseen, our efforts were rewarded, and down we came. But unfortunately there had been a little mistake. The thing at the bottom was not

a bed of roses after all, it was a cesspool full of barbed wire.”

He developed his second theme in a BBC broadcast on March 10, 1942, titled “The Rediscovery of Europe.” He posed 1914 as the dividing line between two ages. Before 1914, “The giants of that time were Thomas Hardy — who, however, had stopped writing novels some time earlier — Shaw, Wells, Kipling, Bennett, Galsworthy and, somewhat different from the others — not an Englishman, remember, but a Pole who chose to write in English — Joseph Conrad.” What strikes him about the prewar figures is their

provincialism on international issues and a naive trust in the future of middle-class reform:

“I think the basic fact about nearly all English writers of that time is their complete unawareness of anything outside the contemporary English scene. Some are better writers than others, some are politically conscious and some aren’t, but they are all alike in being untouched by any European influence.” The provincialism was not only geographical but historical as well. “To Bernard Shaw most of the past is simply a mess which ought to be swept away in the name of progress, hygiene, efficiency and what-not.”

His point is that the writers of the prewar period took for granted the middle-class life of isolated England. Their rebellion against it was a narrow one, over issues that would look small after the trenches of France. He contrasts the whole lot of them to Joyce, Eliot, Pound, Huxley, Lawrence, and Wyndham Lewis: “To begin with the notion of progress has gone by the board. They don’t any longer believe that men are getting better and better by having lower mortality rates, more effective birth control, better plumbing, more aeroplanes and faster motor cars. . . . All of them are politically reactionary, or at best are uninterested in politics. None of them cares twopence about the various hole-and-corner reforms which had seemed important to their predecessors, such as female suffrage, temperance reform, birth control or prevention of cruelty to animals.”

He contrasts this new cynicism to “the shallow Fabian progressivism of writers like Bernard Shaw.” What did it signify? “Partly that was the effect of the war of 1914-18, which succeeded in debunking both Science, Progress and civilized man. Progress had finally ended in the biggest massacre in history. Science was something that created bombing

planes and poison gas, civilized man, as it turned out, was ready to behave worse than any savage when the pinch came.”

He adds: