West Adams Oil Blues

Leslie Evans, in consultation with Michael Salman

My neighborhood is the West Adams section of Los Angeles, just south and west of Downtown. Its miles of historic, century-old Craftsman homes, interspersed with sixties-vintage apartments, house a mixture of recent Latino immigrants, older African Americans, and a minority of whites and Asians. We’ve been in the newspapers a lot recently in disputes with two oil companies over three of their urban drill sites. At one of them, run by the Allenco Energy company, children have been getting sick. Nosebleeds, respiratory problems, headaches, and nausea have been chronic, leading finally to protest meetings, one attended by some two hundred residents, intervention by the federal Environmental Protection Agency and the County Health Department, and a lawsuit by the Los Angeles City Attorney.

At the other two sites, owned by Freeport-McMoRan Oil and Gas, concerns began over ill-kept property, or fears that plans for new drilling would generate noise and pollution. As news reports of the health problems at Allenco spread, neighbors near the Freeport sites heard about a gas leak at one of the well sites and a few accounts of people who may have been sickened by fumes in the past. One public meeting drew more than 300 residents. City officials responded by temporarily closing the Allenco site entirely, while at the Freeport sites routine pumping continues but scheduled new drilling has been put on hold.

What’s Wrong With Today’s Journalism?

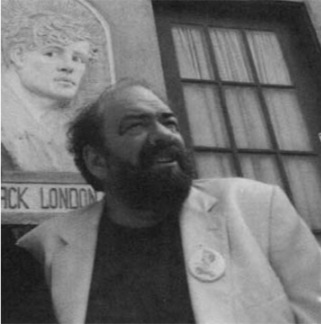

Lionel in front of a bas relief of Jack London, in earlier times when journalism was a hell of a lot better. Photo copyright Phil Stern.

By LIONEL ROLFE

Now that the Los Angeles Times is being orphaned by its corporate overlords, it caused me to think long and hard about this terrible business I’ve been in now for upwards of 50 years.

First there was the personal shock. On many occasions back in the good old days, I used to prowl the long hallways of the Times’ building because I was doing a lot of writing there. And even today I enter into the hallowed halls of the giant building on First and Spring streets and all around me I see the devastation of a war against the newspaper. Its amazing how the same hallways feel so different in different eras. Things have been on a downward spiral ever since the Chandler family sold the paper to the Chicago in 2000.

Back in the ’60s, the cityroom reeked with a sense of confidence. True, even back then oldtimers were uncomfortable because publisher Otis Chandler had allowed his mother “Buffy” to remodel the city room so it looked like an insurance company’s executive offices. No longer could you throw your cigarette butts on the ground and grind them into the floor with your soles and heels. The carpeting was corporate luxurious, and ashtrays and private places to hide your hooch were conspicuous by their absence. Read more

“Amigos” By Irma M. Olmedo

By IRMA M OLMEDO

There were three, three of them, three of them chasing me, and even though the cobbled stoned street was filled with people talking and laughing, no one seemed to notice or try to stop them. I sped down the garbage-strewn sidewalk, across the street with its cracked, uneven pavement, around a bend. The three mangy dogs raced close behind me. I quickened my pace, crossed the next street, evading the flashing cars that honked their horns as I darted in front, dodged between the uneven hedges beside a mustard yellow wooden house and an abandoned car, its rusted fender dangling from the frame, fled to the back yard thick with overgrown grass and weeds. The three dogs continued the rapid chase, speeding right behind me, faster and faster, just a few feet away now, nipping at my exposed ankles. I should have worn my tenis rather than my old open-toed chanclas this morning so I could outrun them and get away. Straight ahead I dropped my grocery bags in the weeds and trying to catch my breath, I grabbed a low tree branch full of tamarindo, pulled myself up just in time to escape the gray skeletal mutt closest to me. But the branch gave way. Now I was falling, falling, falling, the dogs barking wildly below, their sharp teeth exposed, their eyes flaming against the bright sunshine. Suddenly I felt a tug at my arm, someone was shaking me. “Maria, Maria, wake up, wake up, you’re having a nightmare,” Cheito, my husband, whispered reassuringly. My heart was racing, I was sweating, exhausted, out of breath. Again, the nightmare of the dogs.

The nightmare of the dogs had been an ongoing terror in my adult life. The chase was always the essence of the nightmare, though the mangy dogs, in swift pursuit, never caught me. I couldn’t recall any incident that might have triggered this fear that followed me from early childhood. If I saw a dog crouching on the narrow sidewalk in the cobbled stoned streets of Old San Juan, I would quickly cross to the other side, even if the dog were on a leash. The dog’s size was irrelevant to the magnitude of my fear. Large or small, it was all the same to me. And if a dog looked directly at me, I would avert my gaze. I knew they smelled my fear and were emboldened by it. Why would they bark only at me and not at others who passed them by?

It didn’t help that the dogs in my barrio were often left to fend for themselves. People had been hungry during the war, but dogs were famished. Barrio families didn’t have leftovers. Meat and even bones were scarce. Starving dogs were angry dogs, running in packs and scavenging for whatever they could find. Scavengers were not selective.

The war ended but people in my barrio remained poor. Many of my neighbors considered leaving Puerto Rico to look for jobs. “Mira, en Nueba Yol hay trabajo.” they said. “There’s work in New York!” “No hay que hablar inglés para trabajar en las fábricas.” “You don’t have to speak English to work in the factories.” “No necesitas experiencia.” “Puedes ganar hasta un peso la hora.” “Forty dollars a week.” I heard these words up and down the streets of my barrio and in the local bodegas.

Forty pesos a week. Mucho dinero! Cheito earned only 17 a week working at the local print shop, muy poquito for a man with three children. Every payday after he played the lotería to try his luck, the money was even less. No wonder he ended up in the barra drinking rum and trying to cheer up before coming home to face me. “What’s an hombre supposed to do if he has bad luck? Surely, I could understand that! Didn’t I always say I’d had some luck in marrying him?” Only from my inflection could he guess what kind of luck I meant.

My sister, Goyita was convinced that I would be better off in Nueba Yol. “Remember that even as a widow, I made the trip myself 5 years ago and got a factoría job sewing brassieres,” she reminded me. “I managed to make enough pesos to bring my three children six months later. I even met a good man and got married. Now we’re all living comfortably in Los Proyectos. We got a 3 bedroom clean apartment without rats and roaches and with a toilet and bath inside. Why, if you come with Don Cheito he would get a job and a clean proyecto apartment, maybe even in the same building in Losaida.” That was what Puerto Ricans later called the Lower East Side of NY.

So she and I began to scheme about how I could make the move with my family. “I could pay for your plane ticket, Maria, ” Goyita offered. “ And Cheito’s sister can pay for his. You can live with me until Cheito finds a job and an apartment. Sooner or later, all of you will live pretty well. All you need to do in Nueba Yol is get a job, maybe two, and work very hard.”

So this is how I became acquainted with dogs in Nueba Yol. Those dogs were different from the mangy strays crouching on the corners of my Old San Juan barrio looking for a handout or chasing me in my nightmares. Nueba Yol dogs led the good life, strutting down the streets on a leash with a rhinestone collar, wearing a crocheted wool coat in winter to keep warm. Imagine that! People really made coats for dogs! No wonder there were so many factoría jobs in Nueba Yol if even dogs had to have coats. And no wonder Nueba Yol dogs behaved so well — they rarely barked at passersby. They weren’t hungry, so why make a fuss?

Nueba Yol was filled with surprises. Even shopping at the huge, brightly lit supermercado nearby was an adventure. My children loved those stores where people filled carts with their groceries. Products were displayed looking so fresh and attractive that I wanted to buy a little of everything. And, oh, the choices! Even if you just wanted to buy oatmeal, what my family usually ate for breakfast, there were many different kinds to pick from: instant or regular, with or without sugar, with cinnamon or pieces of dried apple, in big boxes or individual packets. The bread aisle was also a wonder. There were breads in all colors and shapes, white, brown, black, round or long, sliced or whole, sweet or sour, mixed with nuts or raisins. In my Puerto Rico barrio I could buy either pan de agua or pan dulce, both of which I loved, but you had to eat them in one or two days because they would quickly get stale. American breads would last for weeks, packaged in nicely decorated sealed wrappers, sometimes with pictures of healthy-looking athletes. Unfortunately, the supermercado didn’t have many boricua foods. For that you had to go to La Marqueta under the Williamsburg Bridge, where you could buy plátanos, spices for the sofrito to season my Puerto Rican beans and other things like really good Goya rice and Bustelo coffee for surviving those frigid New York winters.

What I couldn’t understand was why Americanos ate dogs or cats. A large aisle in the supermercado had cans with pictures of dogs or cats. In Puerto Rico even hungry people never ate dogs or cats. Dogs and cats could be pets but if they were abandoned strays, no one would even want to go near them. But here in Nueba Yol I heard people order hot dogs on the street. They looked like sausages and must have been made out of dog meat or why call them hot dogs? The men at the pushcarts would put a sausage in a long roll of white bread, add onions, some green stuff, ketchup and mustard and sell the hot dog to hungry customers who were always in a hurry. Those hot dogs were especially popular with Americano kids who bought them from the carts rather than eat the lunches served in the school cafeteria. I couldn’t understand why so many Americanos loved hot dogs. I also found it strange to see so many well-dressed Americanos filling up their grocery carts with cans with the pretty smiling dogs or cats on the labels. How cruel to put pictures of happy animals on the cans and boxes! Americanos son locos, that’s for sure. They had crazy ways of doing things. But who knows? Maybe that meat was nutritious. Americanos were much fatter than Puertorriqueños and always looked hearty and well fed. Look at how tall the teenagers got! Few Puertorriqueño kids got to be that tall and husky. It had to be the Americano food, including the cans with the pictures of the cats and dogs.

I hesitated to buy any of that meat for quite a few months. Sure, I was adjusting to the winter weather, to having to wear a coat, hat, gloves and boots whenever I went out in the frigid cold and snow. I was also learning English, important words like pliz, Sank you, esqiuz mi, I sorry, bery nice, mucho money. But eating cats and dogs was going to take more time to get used to. Maybe one day I would buy a can with a pretty dog on it and make a sofrito for it like I did with pig when I cooked it for Christmas in the campo where I grew up. I would mix it with a little onion, salt, garlic, pepper, olive oil, oregano, cilantro, and tomato sauce. That should make it taste pretty good, maybe almost like pork. I’d have to experiment first before feeding it to my family. Fortunately, Don Cheito was not a fussy eater. He was learning to eat what Americanos liked ever since he started working at the factoría. Maybe it didn’t matter to him if it was Puerto Rican pig or Nueba Yol dog as long as it was well seasoned and served with rice and beans, topped off with a strong cup of café con leche.

Maybe Americano dogs taste different from Puertorriqueño dogs, I reasoned. That must be why Americanos like the meat so much. Everyone in the familia joked about how doña Luisa treated her dog Baby, pampering him and feeding him the best food in the house. Doña Luisa never married but had always wanted children. Instead she got a cute little fluffy white puppy to keep her company and fill her empty childless household. Doña Luisa rarely left her 2nd floor tenement apartment on 116th Street in El Barrio because she didn’t want to leave Baby alone. Whenever there was a family party, a taxi would pick her and Baby up and take them home. Baby was too delicate to suffer the cold and snow, even with the coat she had knitted for him with the fur collar. “Baby eats just like a baby”, she’d say. She even got a machine to grind vegetables and meat real soft so Baby wouldn’t have to chew too hard and his tummy could digest the food well. Doña Luisa prided meself on how Americana she was becoming from having lived for so many years in Nueba Yol. I thought she was as loca as Americanos. Luisa had been in Nueba Yol too long to remember what dogs were really like.

One Friday night about six months after my arrival in Nueba Yol, I finally decided to experiment with the supermercado cans of dog meat. I prepared my sofrito first, mixing up 5 cloves of garlic, one chopped medium onion, 6 peppercorns, and some other herbs that I bought at the marqueta, cilantro, recaito, achiote for color. I chopped it all together, using my moltero to grind up the garlic, peppercorns and spices into a moist paste. I mixed everything in olive oil and sauteed it with tomato sauce in my big black caldero, adding 2 oregano leaves for additional flavor. Instead of salt, I decided to use olives and capers, which were already salty. As I cooked the sofrito, the criollo smell filled the entire second floor apartment, even seeping out into the hallway all the way to the broken elevator.

I had selected a medium sized can with a cute, smiling, brown dog on the label after watching which cans Americano shoppers liked best. I was pleased that it wasn’t too expensive since I always watched my food budget carefully. Don Cheito’s measly salary didn’t allow for luxuries and buying foods that Americanos liked was not a purchase I could defend to him.

Would the meat look like chicken, beef, or pork? What might it smell like? I opened the can with great anticipation. To my disappointment, the color was unremarkable. The smell was unpleasant and the brown mushy meat didn’t look at all appealing, but I could fix that with my sofrito. I might even add a little pique, the spicy picante salsa I made for special occasions.

For Cheito, dinnertime was the best hour of the day. His short, stocky frame and rotund belly attested to his love of a good meal. The aroma of the sofrito made him look forward to one of my specialties. One thing he knew for sure, I was a terrific cook. He especially liked my fricase de pollo, which I always seasoned to perfection, he’d say. The roast pork and arroz con gandules I cooked for Christmas were not bad either. And when I got together with my sisters Goyita and Milady to prepare pasteles and alcapurrias, stuffing them with pork, garbanzos and raisins, he fell in love all over again. “All a man really needs for a happy and fulfilled life is a wife who can prepare a good spread!” he’d often assert to his co-workers. “Maria is rarely adventuresome with her cooking, sticking faithfully to the traditional foods that she had prepared and eaten in her barrio. But that’s fine with me. I can even be satisfied with a hefty serving of plain rice and beans as long as the seasoning is just right. And Maria certainly knows how to prepare sofrito. “

Taking a cold beer out of the refrigerator, Don Cheito sat down, anticipating a new treat. He took a large mouthful of this new dish. He chewed a little and swallowed. He took another hefty mouthful, chewed it more slowly and swallowed it, a puzzled look on his face. He could taste my sofrito with the garlic, onions, and spices he loved. But, what, exactly, was that texture? It wasn’t chicken, pork, or steak. He had eaten rabbit and goat stew but this dish wasn’t that either. He was also fond of cuchifritos, made from various parts of the pig and sold in local cuchifrito stands on Delancey Street. He especially liked tripitas, “sweetbreads” his American coworkers called it, as they glanced suspiciously at it when he brought it to the factoria for lunch. “What a strange name for food for poor people,” he’d say. Though his co-workers politely turned him down when he offered them a taste, he was proud of the great variety of dishes that his fellow boricuas cooked from all parts of the pig. “Those Americanos sure don’t know what they were missing. Most of their dishes are rather bland and uninspired.”

This new dish that I had prepared looked a little like spaghetti sauce, but seemed to have a different texture than the ground beef I usually used. The whole family had learned to enjoy spaghetti and his coworkers often were impressed with how much better my spaghetti tasted than the kind their own wives made with the bottled Ragu sauce from the supermercado. I always added my own sofrito to the sauce, giving it a rather unique taste. After chewing the 3rd spoonful of this new dish, Don Cheito stopped. “Maria, what is this? What kind of food are you giving me? I don’t think you ever made anything like this before.”

“Ay, amor it’s only some food that los Americanos like to eat. I saw them buying cans of it at the supermercado and I thought you might want to try something different.”

“Americano food? Cans from the supermercado? What are you talking about? Let me see the can.”

“Here it is. See the picture of the cute brown dog on the label. Every week I saw Americanos buy these cans in the supermercado, so I figured I’d fix some up with the sofrito.”

“Ay, Dios mio Maria” he groaned after reading the label. “This is not dog meat. This is meat for dogs! Maria, people don’t eat it. Americanos buy it to feed their dogs!”

“What do you mean that los Americanos feed it to their dogs? Special meat for dogs? You mean Americano dogs don’t eat the leftovers like Puertorriqueño dogs? You mean people buy special foods in the supermercado for dogs? What about cats? I also saw cans with pretty kittens on the labels. You mean to tell me that all those cans are special food for cats too?”

I gritted me teeth, shook my head, and with a look of disgust dumped the meal in the trash. “What a waste of time, money, and sofrito!” I said aloud. “Los Americanos sure are locos if they have special foods for their pets! I’ll never become an Americana with their weird ways. Imagine, selling special foods in the supermercados for cats and dogs! I’ll have to tell Goyita and Milady about this so they don’t make the same mistake.”

Luckily, I had also made rice and beans. I fried two ripe plátanos and used the extra sofrito for bacalao, the dried codfish that I always kept handy for emergencies. Cheito and the kids wouldn’t go hungry.

Eventually the dog food dinner became a big family joke that got better and more elaborate each time it was retold. I even learned to laugh about it. It was one of many anecdotes in a long line of events, some humorous and others unpleasant, that were expanded in the retelling, events that Cheito and I experienced as we learned to become Americanos.

Becoming Americanos came to an end when Cheito and I decided to return to Puerto Rico in 1970. Puertorriqueños in the Lower East Side and the New York Barrio had been saving their pesos to return to their viejo San Juan. The economic boom of the late 1960s became an incentive for Goyita who led the return for my family: “Mira, Maria, you should see the beautiful casitas that are being built in Levittown; they’re made out of cement, not wood, so they can withstand the hurricanes. They have green lawns in front and gardens in back for growing tomates, beans, mangos, bananas, lemons, whatever you wanted to grow there. If you return to Puerto Rico, Cheito can set up a printing press next to his casita and now that he knows ingles he can print all kinds of documents, even bilingual ones.”

So we returned and moved to Levittown and Cheito built his print shop in the marquesina, the carport attached to the house. No need for a carport since he had no car and had never learned to drive in Nueba Yol. Like many Neuyorricans, he had taken the F train back and forth to work every day for years. Since Levittown was a new community, he anticipated getting all kinds of print jobs as people opened up businesses in their carports. I discovered a clientele for my Puerto Rican specialties and homemade sofrito. Younger women had full time jobs and little time to make traditional meals from scratch so I would sell my homemade specialties.

Much had changed in Puerto Rico in the two decades since we’d left and Levittown was the place for change. On the main street two blocks from our house was a huge, air-conditioned supermercado just like the ones in Nueba Yol, with aisles lined with many choices of coffees, breads, beans, and other products. Meats were packaged in sturdy cartons or sealed in cellophane with prices and weights marked clearly on attractive labels. The best part, however, was not only did these supermercados have Americano products, but Puertorriqueño ones as well. They even had cans with pretty dogs and cats on them! Of course, unlike in Nueba Yol, the animal aisle was tiny. Los Puertorriqueños were becoming just like Americanos, but not quite. Their dogs still ate rice and beans, pork, and other leftovers from their owner’s tables. And I vowed I would certainly not make the same mistake I had made in Nueba Yol. I would not buy one of those cans and cook it, not even with good sofrito!

Many home owners in Levittown were also from Nueba Yol. Like in Nueba Yol, they spoke Spanglish, español and ingles. They were the puertorriqueños who had made it and were coming back home, some bringing dogs and cats with them. Backyards had casitas with signs sporting names like “Grande,” “Pepe,” “Negro,” “Macho” or “Superdog”. The bigger houses with huge fences had signs proclaiming “Cuidado Perro!” “Beware of Dog!” for the watch dogs that wealthy people kept as security against burglars.

“Mira, these Levittown homeowners quickly figured out that big dogs are good guard dogs for their property” Cheito would say. “In Nueba Yol, we were never burglarized. Everyone knew that only poor people lived in the proyectos and what could be stolen from the poor? But Levittown is different. It’s wealthier than Cataño, that barrio next door of people with little money who had never left Puerto Rico.” Neighbors often recounted stories about Cataño burglars breaking into Levittown houses to steal televisions, record players, whatever they could carry.

I had stopped having nightmares about dogs for a long time. I rarely saw loose hungry dogs barking at people in the streets as most were confined to their back yards. Occasionally a mangy stray wandered the outskirts of Levittown, sometimes around the beach where family outings were popular during hot summer weekends. People cooked their roast pork, their pasteles and alcapurrias, their arroz con gandules, and topped off the feast with coconuts knocked down from the palm trees. The leftovers from the criollo banquets, piled up in overflowing trashcans, were enough food for dogs to feast on.

In the fall, however, the number of strays in Levittown grew. People thought that the dogs were coming from the beaches. The neighbors would say “It’s the people from Cataño who are to blame; since they’re unable to control the strays, they truck them to Levittown. They know Levittown is better able to feed hungry dogs.” I knew that Levittown had good town services, including dogcatchers; if residents got too annoyed with the dogs, they would get rid of them. Cataño had never had dogcatchers. They had bigger prey to catch, drug pushers, burglars, and gang bangers, for example. Dogs were not part of that agenda.

Near the end of December, Cheito and I were expecting our daughter, Mima and her husband Bob for the Christmas holidays. Mima had moved to Wisconsin after marrying a gringo professor who loved to swim and snorkel. Trips to Puerto Rico were a special treat, especially around Christmas when Wisconsin winters made them long for sand and surf. I looked forward to preparing the special holiday dishes that Mima loved and Bob was learning to appreciate. Cheito would be sure to share the story of my dog food meal, a story that he always spiced up the same way I had spiced up the meat with my sofrito.

Mima always thought coming home was great since I would cook her favorite foods. Cheito and I would regale them with neighborhood gossip and political controversies. Mima and Bob enjoyed listening to Cheito’s outrage at the neighbor’s politics: “Can you believe that fool favors Statehood for Puerto Rico? Everyone in his right mind knows that the Commonwealth is the best future for the island.” I would forcefully challenge his arguments. “Puerto Rico needs to be independent,” I’d proclaim. “My years in Nueba Yol taught me that los Americanos are locos. We Puertorriqueños can never be Americanos!“

For several evenings, Cheito and I furtively put the dinner leftovers into a Ziploc bag and stored it in the refrigerator. I didn’t want Mima raising questions as to why I was saving leftovers. I preferred to have her think that this was our way of recycling since leftovers in outdoor trash cans in the heat would stink, overpowering the sweet smell of the lilacs that lined the front of the patio. One cool but humid evening, Mima went out to sit on the patio to enjoy the pleasant breeze after sundown and hear the singing of the coquis. The flowery bushes exuded a sweet smell in the mild evening air. The street was rather quiet. Most families were indoors watching television or preparing for the big feasts of Nochebuena, Christmas Eve. Cheito came out with me close behind. We couldn’t pretend anymore. Standing erect just behind the patio gate and cupping his hand to his mouth, Cheito shouted, “Amigooos, Amigooos!” All of a sudden a pack of dogs appeared by the patio, barking and wagging their tails. I handed Cheito the plastic bag with the leftovers. He carefully distributed the scraps in plastic bowls and set them before the dogs, who greedily attacked every scrap of the feast. Cheito watched and smiled.

Then, he strolled back to the patio with a sheepish look on his face. “I don’t know what I’m going to do with Maria”, he complained. “I tell her that if she’s so afraid of dogs we shouldn’t feed them because they’ll just keep returning. At first it was only one or two strays. Now all the dogs in the neighborhood spread the word about where to get a good banquet. Maria, I can’t figure you out,” he shouted to me, with an amused grin on his face.

“Ay, nena” I whispered to Mima. “Did you ever look into the eyes of a hungry child? Well, the eyes of a hungry dog have the exact same expression. Ay bendito! I feel sorry for those poor orphan dogs that no one cares about or cares for. Now that we have enough food to have leftovers, what else do I want with it? Why should the leftovers be wasted and dumped in the trash when I can share them? I don’t have to go to the supermercado to buy fancy food for these dogs. These amigos puertorriqueños eat exactly what we eat. They even like my sofrito!”

Exit From Eden: Excerpt From A Novel In Progress By Mary Reinholz

Mary Reinholz, from 1970 when she lived in Laurel Canyon. Photo by Don Strachan

CHAPTER ONE

Fanned by the Santa Ana winds, the September brush fires started a couple of weeks before I blew out of Los Angeles on a cross country road trip heading East, far away from the sprawling star-studded eden of my youth.

Twice I drove up to fire lines of the Malibu hills in my little MG convertible, top up, radio blaring Jim Morrison’s “Baby, light my fire,” watching dead trees explode in the darkness. I was 25, a California girl reporter who once went to convent schools about to head into the unknown. Fire on the mountains inspired the thrill seeker in me, the would-be anarchist who had decided it was time to burn my bridges, trash the past and live on the edge.

Back in my Laurel Canyon cottage, I felt my hair was on fire, maybe because my spent love affair with a pacifist writer made me want more than what he could deliver. I longed for him, the smiling activist I called Orange Man, but it was like clutching at air.

“The East is red!” I began murmuring when the fires jumped over the freeways and into the hills and rolled towards Malibu like a river of flame. I had this vision of an Eastern Utopia in Vermont where I might meet a hearty hippie farmer, live in a beautiful farm house, make babies, books and revolution. Nothing happened that way, but Orange Man’s decision to leave me and live on the beach was the catalyst for my decision to get the hell out of L.A.

He had advised me to my dump little hillside nest, on which I had an option to buy like a good bourgeois babe, warning, “It’s best to travel light without a house on your back.” Bad advice, but it seemed perfectly reasonable at the time.

After all, reason did not rule in that waning summer of 1970, one year after the Manson murders one canyon west of mine and two years after the assassination of Bobby Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel.

”You want to redeem this horrible experience you had with Orange Man by hitting the road,” mused my costume designer friend Tina Missouri, who had worked on the set of “Bonnie and Clyde.” She lived up the block from me on Lookout Mountain Road in a house she claimed had a bedroom fashioned from wine barrels. ”You want to take your chances. But you might miss it here. Of course, you won’t miss the phonies here and the temperamental assholes of the silver screen.”

“I had an offer to room with a feminist filmmaker who lives with two lesbians in this great house in the Hollywood Hills,” I told her. ”I considered it, because I’m really lonely now and it would help sharing the rent. But Jesus, I don’t want to wind up a lesbian.” Read more

Sometimes It Was Fun

By PAMELA ADAMS HIRST

My poor parents; they were both so weak, so damaged. The war damaged Daddy and Daddy damaged Mama. I’m a baby boomer. When my sister was born, four years after me, the violence began. Today they would call it post traumatic stress syndrome. But back then they called it shell shocked.

Sometimes it was fun hiding from Daddy. I remember once when Mama said we were going to hide, said we were going to spend the night up in the attic. We made pallets on the floor. It was fun, just like when we went visiting out in the country to see my cousins Patsy and Gill at the horse farm.

It was like camping. Not that we knew what camping was. But we had an old oil lamp left over from the blizzard the winter my sister was born. Mama brought the bucket up from under the kitchen sink and the toilet paper, too.

And besides, up in the attic it was cheerful; we played cards and I Spy while the shadows danced around on the raw planks like fairies. When we went to bed we all curled up together like spoons.

Late that night we heard my father come in the kitchen door. We stayed really quiet. He spent a lot of time down there running water in the sink. He never once called out our names. Read more

Lionel’s Memories From A Menuhin Past

This is a picture of my mother, Yaltah Menuhin, a bit before she produced me, her greatest opus. (Just kidding, honest. Kidding on the dime, isn’t that what they call it?) Anyway, Larry Young of Ventura, whose family was close with mine, found this and sent it to me. Below is another picture he sent me of my uncle Yehudi with his first wife Nola and daughter Zamira.

Honey Sees From the Sky Descends an Angel

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

Old people comprised most of the audience when I saw Saving Mr. Banks. They sat through the film without moving their white heads and stayed to the end of the subtitles. They were entranced. They could have read the Mary Poppins series, which began in 1934, as children. They could have read the books to their children. Everyone knows Walt Disney. His Steamboat Willy came out in 1928. Each of the old people in the audience grew up with Disney animations and with Walt on television. Disneyland in Anaheim is 58 years old. I was one of the children who went to it soon after it opened.

There were no parking structures but asphalt lots. Women wore high heels, and they got stuck in the asphalt. Real leeches floated in big clear glass containers set on the counter of the Main Street pharmacy.

Both the P.L. Travers book series and Walt Disney affected the way a lot of people saw the world when they were children. The time we spent as children seems like a very long time. The beginning of summer vacation seems like the beginning of forever with adventures still unaccomplished ahead like a vista without a horizon. The older we get, the faster life goes by, and so childhood seems to us to have been a longer period than it was, and what happens in childhood is important. Read more