Iraq on Its Own Terms

Leslie Evans

The dominant American liberal narrative about Iraq is that George Bush lied to drag America into a pointless war that destroyed a stable, secular, if dictatorial, country at the cost of the lives of 4,486 U.S. military personnel and at least 120,000 Iraqis, possibly many more, costing a trillion dollars, and leaving behind a chaotic ruin riven by bloody sectarian rivalries headed into civil war. Marxists would add that the war was a predatory attempt by American imperialism to create a client state and take control of Iraq’s oil.

There is a certain amount of truth to these narratives but they are more about America than Iraq. Counting up the dead doesn’t tell you what the Iraqis in their various ethnic and religious groupings were themselves fighting for, whether they believe they were better off under Saddam Hussein or not, and tends to treat them as undifferentiated and passive pawns or victims of the United States and its coalition partners. Just maybe most of them don’t see it that way. Hate George Bush and Dick Cheney all you like. More power to you. The war was a disaster for America, and the Iraq that exists today is a far cry from the shining pro-West democracy that Bush and the neocons promised. But don’t lie to yourselves about the people of Iraq, either out of ignorance or out of hatred for the Bush administration. In any case, maybe the fact that Barack Obama was the Commander in Chief of the U.S. forces in Iraq for more than a third of the time they were there may lead you to consider that the war, ill considered or not, was not simply an attack on Iraq’s peoples. (Marxists excepted here.)

For those willing to look a little further into the past, the blood letting in Syria and Iraq is at least in part a consequence of the secret 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement during World War I, which carved out French and British mandates, later validated by the League of Nations, in which the Ottoman Empire was abolished, with France gaining administration of what is now Syria and Lebanon, the British getting Iraq, Transjordan, and Palestine. The charge against Mark Sykes and Francois Picot is that they simply drew lines on a map that grouped together peoples with radically different beliefs, building eventually explosive elements into these new states. Certainly since the region’s borders were codified in 1921 the mandate states have been the most unstable: Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine/Israel.

Yet if we go further back in assigning responsibility for the two current civil wars we will find that Sykes and Picot’s greatest sin was not a deliberate herding together of ethnic and religious groups that harbored deep mutual hostilities, but that they took whole regions of the Ottoman Empire as is, failing to undo potentially explosive proximities that were part of Ottoman policy. After the Ottoman conquest of the region four hundred years ago, the Turkic overlords locked religious and ethnic rivals cheek by jowl and, at least in Iraq, deliberately imposed minority rule over peoples who would still be oppressed and brutalized when the Americans arrived in March 2003.

The starting point for unraveling Iraqi politics is its demographics, and how they came about. Index Mundi’s 2013 estimates set the population at 31.8 million. Of this, Arabs are 75-80%, Kurds, who have their own language, 15-20% (other ethnic groups, mainly Turkoman, Assyrian, and Mandean, make up 5%). Religiously, 60-65% of the population are Shiites, 32-37% are Sunnis. But the Kurds are part of the Sunni count, and as an oppressed people under Saddam’s Sunni dictatorship, they were and remain supporters of Saddam’s overthrow by the Americans. That leaves the Arab Sunni population, the base of Saddam’s rule and of the current ISIS invasion, at something like 17%, or about 5-6 million. The nine-year American war was overwhelmingly with a militant minority of the Arab Sunnis, themselves a small part of the population – and with foreign Islamic radicals who joined their cause.

Shiism was introduced into Iraq in the 10th century by several Arab Shia empires, most important, the Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171). But Sunni Islam became dominant in the Arab lands, while Shiism was made the state religion in Persia under the Safavid dynasty (1501-1736). The differences to an outsider seem as inconsequential and arcane as those between Protestantism and Catholicism, another religious rivalry over which much real blood has been shed.

The split in Islam occurred immediately on Muhammad’s death in 632 CE. Those who became the Shia demanded that the succession as the leader of Islam should be handed down within Muhammad’s family as an inheritance determined by Allah, like kingship in the West. Their candidate as the first caliph was Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali ibn Abi Talib, married to Muhammad’s daughter Fatimah. Those who won the argument and became the Sunnis instead called a sura council and elected Abu Bakr. Ali served as the fourth caliph, but was assassinated in the fourth year of his reign, 661. After the first four, the caliphate passed into the hands of successive dynasties, which, as they did not emanate from Muhammad’s bloodline, defended the elective principle of the Sunni sect. The Shias reject the legitimacy of the Sunni line of caliphs. They represent only 10-20% of Muslims globally, but 38% in the Middle East. The only state in which Shia Islam is the state religion is Iran, the Persia of history. Arab Shiites are the majority in Iraq, but a large minority in Lebanon and, in the closely related Alawite sect, constitute the minority base of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad.

The Sunni Turkic Ottoman Empire conquered Iraq in 1533 and ruled until 1918. During those almost 400 years Ottoman policy was to use Iraq as a buffer state against its Persian adversary. As the Turks did not trust Iraqi Shias to remain loyal in face of their Persian coreligionists, the Ottomans imposed Sunni rule throughout.

The majority of Iraqis were nomadic tribesmen and nominally Sunnis. In the late eighteenth century the Ottomans forcibly compelled most of them to become sedentary agriculturists. In protest, and in part under the influence of Arab Shias at the holy sites of Najaf and Karbala, the tribesmen underwent a conversion to Shiism that expanded throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

So Shia Iraqis endured four hundred years of subordination to Sunni rule, though they were generally more docile than the similarly abused Kurds.

Kurds had a similar history but were more severely persecuted and rose in revolt repeatedly. Originally an Iranian people, there were a number of independent Kurdish kingdoms in the tenth and eleventh centuries, some surviving into the fifteenth century. The Kurds of Anatolia were conquered by Turkic invaders in the eleventh century, some rising to important positions in the regime. The best known was Saladin (1174-1193), the first sultan of Egypt and Syria and the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, the famed opponent of Richard the Lion Hearted and the Crusaders.

The Kurds became an oppressed people when the Ottoman Empire annexed Armenia and Kurdistan in 1514. There were major Kurdish uprisings in 1847 and 1880. The Kurds, loyal to their Sunni Islam, strongly opposed the secular reforms of the Young Turks in World War I. Constantinople retaliated against its inassimilable minorities with the Armenian genocide of 1915 in which 1.5 million Armenians died. The lesser known Kurdish genocide took place at the same time, with the mass deportation of 700,000 Kurds to their present location in northeast Iraq, in which some 350,000 died. There were persistent Kurdish uprisings after World War I: in 1925, 1930, and 1937-38.

The point of this history is to show that the excluded and oppressed position of Iraqi Shiites and Kurds predated British and French intervention by centuries, and the lines on the map drawn by Mark Sykes and Francois Picot did not deliberately push together hostile peoples but simply took the Ottoman provinces, or vilayets, as they then existed and apportioned them to the mandate powers. To Britain went the whole of Iraq, which was composed of the Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra vilayets. The Syrian vilayet, which was subdivided into smaller sanjaks, comprised present day Syria, Jordon, Lebanon, Palestine, and Israel, and parts of Turkey and Egypt. It ran from southern Turkey in the north to Alexandria in the south. France took Syria and Lebanon, Britain the rest, giving the greater part, Transjordan, to the Hashemite monarchy and reserving the smaller part of Palestine to fulfill its pledge in the Balfour Declaration to sponsor a national home for the Jews.

Saddam Hussein’s Secular State

Already by World War I open colonies had become unacceptable. With the Ottoman Turks fighting on the German side, Britain promoted the Arab Revolt to break the Turkish hold on the Middle East. Britain backed prominent Arab dynasties to rule in the new states that emerged. The venerable Hashemite Kingdom of the Hejaz that ruled Mecca and Medina in western Arabia provided princes: Faisal was named king of Syria, but the French expelled him, leading the British to offer him the kingship of Iraq. His brother Abdullah became king of Transjordan, which as just Jordan is ruled by the Hashemites to this day. In Iraq, Faisal’s son and successor was murdered in a July 1958 revolution that installed a military government, in turn overthrown in the Baathist coup of July 1968.

The Baath movement, later solidified in Syrian and Iraqi parties, was founded principally by Michel Aflaq in Paris after the fall of France. Looking for an anticolonial modernism, Aflaq first was attracted to Stalin’s Russia, but then found German Nazism more congenial. As Paul Berman put it, “The post-communist Aflaq took to mooning over the Arab seventh century. He imagined a return to yore through a revived appreciation of blood ties. He attached to those ideas the modern-sounding concept of socialism, thus arriving at a national-socialism. He identified the spiritual loftiness of the Arabs. He located ethnic enemies, some of whom, by odd coincidence, turned out to be the very enemies that German nationalism likewise loathed.” (The New Republic, September 14, 2012)

So Baathism began life as an antisemitic racialist and totalitarian doctrine modeled on Hitler’s Third Reich, with Arabs substituted for Germans as the master race. Where Germany revived romantic myths about Odin and the Teutonic past, the Baathists, without becoming Islamists, looked back to the seventh century time of Muhammad and the military expansion of the young Islam as their golden age.

Unlike Islam, Baathism did not advocate a worldwide caliphate but did look toward military expansion to achieve pan-Arab unity. Wherever it took power it installed a one-party state, crushed dissent, and first suppressed and then engaged in ethnic cleansing of groups that did not fit its image of the pure Arab bloodline. In Iraq that meant the Kurds, and the Iranians over the border to the east.

Shiites, at first seeing Baathism as a revolutionary anticolonial movement that might improve their position, joined the party in large numbers, while it was in opposition. As it became clear that, despite its nominal secularism the Baath leadership strongly favored the traditional minority Sunni rulers, Shiite members shrank to 6% by the time the Baath seized power in 1968. They were briefly wooed by Saddam in the 1980s after Saddam’s invasion of Iran, as he needed their willing participation for his eight-year war, and feared them going over to the Shia Iranians. But as the war ended so did any inclusiveness of Iraqi Shias.

Saddam was a central figure in the 1968 Baathist coup. As vice president under an ailing leader, power quickly gravitated into his hands and he emerged as the regime’s strong man, though he did not claim the presidency until 1979. On assuming the office he conducted a purge reminiscent of Stalin’s execution of the Old Bolsheviks who might challenge his authority. Saddam had hundreds of high ranking Baathist officials executed.

The same year the Iranian revolution overthrew the American-backed shah and established a Shiite theocracy under the Ayatollah Khomeini, proclaiming a worldwide struggle to overthrow all of the infidel governments and replace them with ones that adhered to Allah’s laws. This electrified the Arab Shiites of Iraq who for the first time in centuries threw off their acquiescence in their inferior status. Several Shiite groups demanded that Iraq abandon Baathist secularism and follow the Iranian model. At the same time, Kurdish agitation for independence was renewed. The secret police, the Mukhabarat, run by Saddam’s half-brother, retaliated with widespread torture and assassinations.

In a January 26, 2004, essay by Human Rights Watch, whose main point was to oppose the current U.S. invasion, it stated that its records showed that the Iraqi Baath Party since 1979 had murdered 250,000 of its citizens, including 100,000 Kurds. (http://www.hrw.org/news/2004/01/25/war-iraq-not-humanitarian-intervention)

Saddam, implacable toward his critics, like the Saudi kings used Iraq’s plentiful oil money to buy support and quiet dissent. He instituted universal health care and free universal education through college level. Occasionally he would stage an election to show how well loved he was. In an October 2002 vote, Saddam, with tens of thousands of photos of himself plastered on almost every wall in the country, won 100% of the votes.

Little more than a year after the Islamic Republic was proclaimed in Teheran, Saddam, fearing further Islamic radicalization of Iraq’s Shiites, invaded Khomeini’s Iran. The war would last until 1988. When Iran responded with human wave attacks, Saddam retaliated with poison gas. Kurds opened their own northern front, fighting once more for their independence and in support of Iran. They were also met with devastating poison gas. Saddam received major foreign aid as gifts or loans, and was allowed to buy weapons on a large scale.

Best known in the United States was the Iraqgate scandal that began under the Reagan administration. Run by former CIA chief, then Vice President, and later President, George H. W. Bush, it began in 1985, five years into the war. Bush, with Reagan’s approval, put into operation a secret operation to approve American loans to Iraq. They were designated for dual-use materials; that is, the loans, funneled covertly through the Atlanta branch of Italy’s largest bank, the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, were not to buy weapons but were restricted to things that could have a civilian use, such as high end computers, ambulances, helicopters, and chemicals. The chemicals included cyanide from a Florida firm that Saddam used in his poison gas attacks against the Iranians and the Kurds. The loans continued under the George H. W. Bush administration right up to Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990. The U.S. government-backed loans ran to $5 billion, of which Iraq repaid $3 billion and defaulted on the remainder. (For an excellent account see Russ W. Baker’s “Iraqgate” in the March-April 1993 Columbia Journalism Review, available online at russbaker.com.)

Much has been made of Iraqgate, often to prove that Saddam was America’s man and Washington’s instrument to try to crush the Iranian revolution. This misses the consensus among a broad range of major powers, several of which provided far more money, not as loans but as gifts, years earlier, and with no conditions on how it was spent. There were two prime considerations: first, there was a widespread fear of Islamic radicalism and its loudly proclaimed threat to promote religious revolution throughout the world. The fear was no respecter of social systems. Saddam’s biggest backers were the Soviet Union, Communist China, and capitalist France. All non-Muslim states were on edge, enough to close their eyes to the use of poison gas. Secondly, Iraq is one of the world’s largest oil producers and the major states did not want the oil to be controlled by the Iranian mullahs.

In contrast to America’s $5 billion in secret loans for marginal military uses, the Soviet Union provided $33.4 billion in gifts explicitly for weapons, France gave $9.2 billion, China $8.9 billion, and even Brazil threw in $1.1 billion. (The figures are from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (http://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/page/values.php ).

At the war’s end Iran acknowledged 300,000 dead, Iraq 240,000 (http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/iran-iraq.htm). The totals may have been much higher.

The genocidal campaign against the Kurds and smaller ethnic groups in northern Iraq paralleled the last years of the Iran-Iraq war, 1986-1988. Headed by Ali Hassan al Majid, known as Chemical Ali, 250 villages were gassed and 4,000 villages razed out of 4,600, leaving some 100,000 dead.

In sum, two totalitarian movements took root in the Middle East from the 1950s. The more widespread was jihadi Islam, based in religion. The other was Baathism, a conscious and explicit hybrid of Russian Stalinism and Hitler’s Nazism. To say that the latter is secular does not make it more acceptable than religious extremism. The word “secular” misleadingly implies that the Baathist dictatorship was no worse than many other forms of authoritarian or dictatorial regime in the Middle East and elsewhere. Not so. Stanley Payne, one of the prime authorities on fascism, wrote in his 1995 A History of Fascism – 1914-1945, “There will probably never again be a reproduction of the Third Reich, but Saddam Hussein has come closer than any other dictator since 1945.” (p. 517)

The War and After

After the fall of Saddam, the Iraq war was fought by the American-led foreign coalition, the Kurdish peshmerga armed forces, and a large majority of the Shiites against the remnants of Saddam’s fascist regime. The Baathist revanchists were joined by large numbers of foreign jihadi warriors, most notably Al Qaeda in Iraq, headed by the Jordanian militant Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was killed in 2006. This is this organization, with some additional groups, renamed Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham, that invaded Iraq in June 2014 from Syria. Normally when a minority, privileged, and oppressive ruling class is overthrown and then mounts a military assault to try to regain power this is called a counterrevolution. The Iraq situation was complicated by the foreign character of the agency that toppled the old ruling class, an American superpower that had a history of exploitive relations with underdeveloped nations. My view would be that judgment of right and wrong here depends on how the subordinated majority responded. And as George Orwell once told us, war is not a choice between good and evil. It is always a choice between greater and lesser evils.

At least the Kurds and most of the Shiites were jubilant at Saddam’s overthrow. The Americans, however, were ill prepared on what to do next. The neocons, who had persuaded the Bush-Cheney administration of the invasion as a shortcut to establishing an America friendly state in the Muslim heartland, expected that, as in the Gulf War of 1990-91, there would be a quick thrust to take Saddam down, followed by a handover to the Shiite opposition that would wrap things up and the U.S. could leave. That was unlikely in even the most optimistic scenario, as Saddam, as in any one-party fascist state, had destroyed all the organizations of civil society except for some very weak religious-based ones (the Kurds excepted). Moreover, the Shiites and Kurds were not left to themselves to build new state institutions, but were immediately confronted by the defeated Baathists, soon joined by murderous foreign jihadi militants, who instituted a campaign of car and suicide bombing and assassinations.

The Bush government and its military knew little about Iraq, had few people who could speak Arabic, and, fearing sabotage by Iraq’s overwhelmingly Sunni administrative structure, dissolved the Iraqi army and terminated the great majority of Sunni civil servants. While their concern was understandable, and retaining such people had considerable dangers, throwing them out of work provided huge numbers of angry unemployed Sunnis, resentful at both the rise of the, to them, rightfully subordinate Shiites and Kurds, intensified by hatred for the infidel foreigners who had invaded their country and made this possible.

The U.S. troops fought well and intelligently, tried to minimize civilian casualties, and had a certain level of success in helping the new government build from scratch its army and police forces. But the Coalition soldiers had little personal contact with ordinary Iraqis, lived in fortified camps and enclaves, and were sometimes killed by Iraqi security personnel they worked with who were loyal to the insurgents of the old regime.

In a country that had no experience of parliamentary democracy or large existing organizations that could rapidly establish a state structure, the new government sought to include Sunnis, many of whom were not Baathist supporters, as well as Kurds, in the new parliament and top officialdom, while holding down their numbers in the army, police, and civil service. The most recent, April 2014, parliamentary elections, for example, with a confusing number of parties and coalitions, but a large turnout of 62%, gave Maliki’s coalition 158 of 328 seats, or a plurality of 48%. All Iraqi constituencies won seats: The Shias, 170; Sunnis, 43; Kurds, 62; and the smaller ethnicities and religious denominations 24. The Shiite politicians from the first did not agree with the Kurds’ demand for extreme autonomy leading toward independence. The structures that did emerge and the orderly national elections that were held were much more promising than might have been expected.

The most authoritative Shiite religious leader, the Grand Ayatollah Ali al Sistani, was cooperative with the Americans throughout, supported the American-protected elections in 2005 and 2010, and today, after the ISIS invasion, has called on the Maliki government to include Sunnis in leading positions and seek reconciliation with the Sunni minority.

One faction among the Shiites opposed the U.S. invasion. Led by the prominent cleric Muqtada al Sadr, it formed its own militia, the Mahdi Army, within months of the American landing. The Mahdi Army attacked Coalition troops in April 2004 and continued sporadic attacks over the next two years, but had no serious clashes with the Americans after 2006. It did fight with the new national army and police, as well as organizing its own anti-Sunni death squads during the 2006-2008 civil war. Muqtada al Sadr ordered a truce with the Americans and Iraqi government in August 2007 and disbanded his army in August 2008 (though inactive, the Madhi Army retained its weapons and after the ISIS invasion has been reconstituted and sworn to defend Baghdad against the jihadi force).

In the 2010 parliamentary elections Sadr’s political party won 40 of 325 seats, and since the American withdrawal he has presented himself as a moderate.

During the war the Sunni Islamicists in particular adopted the strategy of car and suicide bombing, and death squads aimed at the Shiite civilian population with the avowed goal of exterminating the heretics. Most immediately this aimed to provoke a civil war. That war took place in 2006-2008. In reaction to the jihadi killings the Shiites formed their own militias, which retaliated in kind, reducing the Sunni population of Baghdad from 35% to 12%, as many Sunnis fled the capital.

In June 2007 during the American troop surge, the Americans began to arm Sunni tribes in their heartland of Anbar province. These tribes had been allied with Al Qaeda in Iraq and insurgent Baathist forces, but found them repressive and brutal. This winning over of significant parts of the Sunni populace was a major factor in bringing the war to a close.

The last American troops pulled out of Iraq in December 2011. They left behind a country still faced with regular bombings by the defeated Baathist fascists and by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s Al Qaeda in Iraq, which had now renamed itself ISIS. The almost daily totals of persons blown to bits in Baghdad and other cities that have littered the U.S. press over the last few years give the impression that the war was ongoing on a significant scale before ISIS invaded. While ISIS moved its center of operations to Syria during the civil war there, it retained a small force in Iraq. But the persistent bombing appears to have been organized out of Syria. Brett McGurk, special U.S. envoy for Iraq and Iran, testified before the House Foreign Affairs Committee that almost all of the 300 suicide bombings in Iraq over the previous year were carried out by foreign fighters who entered the country from Syria (Los Angeles Times, June 22, 2014).

The clearest winners of the long conflict have been the Kurds. Subject to genocidal attack under Saddam and faced with daily bombing by the Baathist regime that only President Clinton’s no-fly zone halted, from the early days after the U.S. invasion they were able to use their peshmerga army to hold the Sunni bombers and assassins at bay. They quickly became virtually independent for the first time since the Ottoman conquest in the sixteenth century. They have built a prosperous economy which has enjoyed substantial foreign investment. Even the latest upset with the invasion by ISIS seems to have been more to their advantage than not, as they were finally able to establish their control over the contested city of Kirkuk. It has been reported, but I am unable to verify if true or continuing, that when ISIS captured Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, that they executed many Shiites, but left the Kurdish sector alone.

The Kurds have resolved their long conflict with Turkey, having built an oil pipeline to the Turkish border, while the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad, which was not seriously bothering them in recent years, seems unlikely to try to recover Kirkuk. As the most oppressed of the peoples under the Baathists, this is a humanitarian victory of the first order. That it was bought at a cost that was far too high for America does not diminish its worth to the Kurds.

(By way of disclosure: I have been a partisan of the Kurds for many years. Like the native Middle Eastern Jews, who, as refugees from Muslim countries, constitute half of Israel’s population, the Kurds, despite their Muslim faith, have been a historic pariah people. Though I was not in favor of the U.S. invasion, once done what I most hoped to see was the Kurds winning their freedom.)

The Shiite majority also have ended their exclusion from power that lasted since 1533. That is also no small thing. I hope that American liberals and leftists will not let their justified hatred of George Bush and opposition to America’s rigged entry into and overcommitment in this war lead them to refuse to see that it has freed millions of people from an intolerable situation. That they face new perils today from the same forces that kept them in bondage before the war is not a reason to dismiss what they have won, even should it prove tenuous, or even if the Iraqi Shiites prove more attracted to their coreligionists in Iran than to the United States.

These unquestionable advances for Iraq’s marginalized and often slaughtered peoples do not mean that the country will function as a liberal democracy or even that it will remain a single entity. There are deep divisions among its three principal components that go back many centuries. These differences were held in check by powerful overlords, from the Ottoman caliphs to the monarchs, military regimes, and neofascist Baathists that followed. The solution to the rival aspirations and hatreds is as likely to be separation as accommodation. As Leon Wieseltier commented in a retrospective on the Iraq war issued shortly before the ISIS incursion, “When you liberate people from tyranny, or when they liberate themselves, it is the actually existing people who are liberated. They are suddenly freed for the expression of their previously suppressed identities; and those identities are often intensely tribal and religious. People are not liberalized by freedom.” (The New Republic, March 20, 2013)

The U.S. in the later years of its occupation made a serious effort to make Iraq’s armed forces more inclusive. Kenneth M. Pollack, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute’s Saban Center for Middle East Policy, in a June 14 report writes that the United States in 2006-2009 made a major effort to depoliticize Iraq’s ISF (Iraqi Security Forces). Washington “Pressed Baghdad to accept more and more Sunni and Kurdish officers and enlisted personnel into the ranks. As a result, the ISF became a far more integrated force than it had been, led by a far more apolitical and nationalistic officer corps.” In 2009-2010 Maliki largely undid these reforms, fearing that the Sunni officers were secretly in league with the Baath insurgency. Pollack writes that this made the army more narrowly sectarian but it also involved dismissing competent commanders who Maliki did not regard as personally loyal to himself and substituting loyalists of lower competence. (http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2014/06/14-iraq-military-situation-pollack)

Some Comments on America’s War Aims

I see repeated frequently the charge that the Bush administration – and Britain’s Tony Blair who seconded them on the invasion – were war criminals. One can say that the U.S. had no immediate interest in Iraq great enough to justify the invasion. That the Bush administration lied to get the invasion approved. That the war was not worth the cost in American lives and money. And that the U.S. blunder in purging Sunnis from the army and government cost many lives afterward. But the invasion was not an attack on the people of Iraq. An 80% plus majority were victims of the Baathist regime. The Kurds remain pro-American while the Shiites, though they wanted the Americans to leave after a certain point, are clearly willing to work with the United States and have requested American help in the present crisis.

Most of the killing after the 2003 invasion was by the Baathist fascists fighting on behalf of what had been a minority ruling class dictatorship, and by the Islamists who went to Iraq in large numbers, who targeted Shiite civilians as a deliberate plan by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s Al Qaeda in Iraq to provoke a Shiite counterattack that would electrify the Sunni population and propel them to join the jihadis, a strategy ISIS continues to employ today.

The U.S. war crimes chorus quieted somewhat when Obama assumed command and the country seemed to be doing reasonably well in the last period of the U.S. presence and after the U.S. withdrawal. It has loudly resumed in the wake of the ISIS invasion.

The story that the then-Republican administration just wanted to make Iraq an American neocolony and steal its oil, which would have been a war crime, is simplistic. It caricatures the political currents of the time, which can only be unhelpful in viewing clearly America’s place in the world, its options, and in weighing that administration’s goals, in order to develop an alternative foreign policy that doesn’t just say the U.S. should do nothing abroad and let other countries and forces fight it out while we watch from the sidelines. (I probably will not be able to speak here to my Marxist friends, who believe that all American interventions elsewhere are by definition motivated by criminal intentions.)

The American Right is divided into several factions. Most prominent recently are the libertarians of the Ron Paul stripe, and the much larger wing often called paleoconservatives. These last are now dominant in the Republican Party. They hew to a familiar script: opposition to immigration and social welfare measures, big government, gay marriage, abortion rights, and affirmative action, while supporting Christian fundamentalism, encouraging suspicion of science, and defending whites from the challenges of an increasingly multiethnic nation. They are generally inclusive toward racist currents and sometimes antisemitism. While always for a strong military, paleocons are traditionally isolationist, despite attracting some saber rattling characters like John McCain.

The Iraq war was the product of a third wing of the conservative movement, now very much in the shade: the neoconservatives. They had their brief moment of large-scale influence in the George W. Bush administration. Both they and Bush are now repudiated by the Republican majority as an unacceptable big government deviation from orthodoxy, as well as the party’s desire to escape responsibility for the unpopular Iraq war.

The most prominent neocon figures in the Bush administration were Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle. While the paleocons were always right-wingers, the neocons originated as liberals, many around Washington State Democratic Senator Henry Jackson. Some of their older activists and theorists had been social democrats and a few even were Trotskyists, leading to a widespread, but false, paleocon charge that neocons were a branch of Trotskyism that had substituted a world revolution for democratic capitalism for Trotsky’s hoped for world revolution for proletarian communism. (For discussions of the claim that the neocons were a form of Trotskyism see William F. King, “Neoconservatives and ‘Trotskyism,'” American Communist History, vol. 3, no. 2, 2004, and Alan Wald, “Are Trotskyites running the Pentagon?” History News Network, July 23, 2003.)

Max Shachtman (1904-1972), in the 1930s a central leader of the Socialist Workers Party, then the principal Trotskyist organization in the country, and in 1940 the founder of the Workers Party, abandoned Marxism in the 1950s and as a leader of the Social Democrats, USA, was an important figure in influencing the thinking of the neoconservatives. Another neocon with a Trotskyist background was William Kristol, briefly a Socialist Workers Party fellow traveler and then a member of the youth group of Shachtman’s Workers Party, he was later an editor of Norman Podhoretz’s Commentary, originally a Jewish journal of the anti-Stalinist Left that moved to the right in the 1970s. His son, William Kristol, also influential in neocon circles, began as a Democrat, in 1976 working for New York Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and is today editor of the neoconservative Weekly Standard. Jeanne Kirkpatrick, a Democrat who switched to the Republicans under Ronald Reagan, in her youth was a member of the Socialist Party’s Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL).

A second strand of neoconservatism emanated from the Political Science department of the University of Chicago, inspired by two scholars who taught there, Leo Strauss (1899-1973) and Albert Wohlstetter (1913-1997). Paul Wolfowitz studied under both. Strauss was the more complex, a philosopher far removed from politics. He criticized a strain of what he saw as nihilism that liberalism inherited from the Enlightenment: this was an excessive elevation of Reason as a guide to promoting human improvement through planned social engineering, at the cost of paying little attention to actual history and culture and their importance in shaping people’s identity. In its extreme form this became Communism and Nazism, which disdained all previous culture and viewpoints and imposed their own views by force. In its “gentle” form, he proposed, it led to a generic social engineering without roots in real culture that produced a moral relativism, aimless and hedonistic, predominant in the Western democracies. A conservative interpretation of his doctrines encouraged a strong commitment to inherited values while opposing destructive authoritarian governments and movements.

Albert Wohlstetter was a very opposite personality. As an analyst at the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica in the 1950s he emerged as the principal architect of America’s nuclear defense policy vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. He was appalled at the idea that the government had no plan to deter or to respond to a Soviet nuclear attack except to throw everything it owned at the Russians. He worked to have the government have several alternate plans that would give it the most flexible chance to deter or avoid a nuclear exchange. He opposed U.S. targeting of civilian centers in the Soviet Union, and worked to establish a credible second strike capacity as a deterrent to any Soviet thought of launching a first strike. He advised Kennedy during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, and was a principal adviser to Democratic and Republican administrations for decades afterwards, becoming particularly concerned to halt the spread of nuclear technology that had the capacity to be weaponized. His conservatism consisted mainly in a concern that the United States be vigilant toward its enemies abroad and proactive to head off future dangers. He taught at the University of Chicago from 1964 to 1980, where he chaired Paul Wolfowitz’s dissertation committee.

By one of those curious chances I came to know Albert fairly well, in the fall of 1961 in Los Angeles when I was nineteen and he forty-seven. This occurred through a neighbor and family friend who was a technical writer at the RAND Corporation where Albert and his wife Roberta, a distinguished military intelligence analyst, both worked. I had recently joined the Young Socialist Alliance, the youth group of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party, and Albert and I would often argue about Marxism. I dated his daughter Joan, who also, after they had moved to Chicago, dated the young Richard Perle, later Wolfowitz’s partner in convincing the White House to undertake the Iraq invasion.

In November and December 1961 I lived in Albert and Roberta’s home while they were on an extended trip. I found them to be humane and liberal-minded people.

From their origins in the Democratic Party and the moderate social democracy the neocons were liberal on the social issues where the paleocons were reactionary. They were generally antiracist, supporters of Martin Luther King (but not of black nationalism), of women’s rights, tolerant of immigration and multiculturalism. By the time Wolfowitz and Perle joined, whatever was leftist in the neocon movement lay in the past except for their social liberalism. After the collapse of Soviet Communism they shared in the belief that the future lay with Western style parliamentary democracy. In contrast to paleocon isolationism the neocons were avid interventionists, energetic Wilsonian promoters of political democracy as a kind of cure-all for the world’s ills. They did this, not, as they saw it, for the predatory reasons of the old imperialisms or the greedy corporations, but to advance what many of them called democratic globalism, the shining future that would free peoples from authoritarian dictatorships.

Like most liberals and Marxists, in the unexamined traditions of Enlightenment social engineering and rationalism, they vastly underestimated the power of religion, imagining that it was a superficial matter behind which always lay more weighty economic and political interests. This was least of all true in the Muslim Middle East, where national identity is recent and weak while tribal and Islamic ties are the basic core of civic life. The underestimation of Islam was a major reason why, whatever good came out of the neocons’ Iraq adventure, and I believe some did, it did not and could not achieve the utopian vision they began with.

This brings us to what they thought they were doing in the Iraq invasion of 2003. They did not view the invasion as a humanitarian action, as, for example, a crisis intervention to save the victims in Rwanda would have been if any Western power would have done such a thing, or Bill Clinton’s Bosnian intervention in 1995 following the Srebrenica massacre. It rested instead on a concern at the growth of radical Islamist currents throughout the Muslim world. This had really been going on since the end of World War II, and had accelerated after the Pan-Arab nationalist efforts of Nasser collapsed – first with failure of the short-lived United Arab Republic of 1958-61, then the two disastrous defeats of the secular Arab regimes in the wars in which they attempted to destroy the Jewish state in Israel.

A slowly building turn to Islam as an alternative ideology to failed nationalism ultimately swept the Muslim world, first in its Shia section with the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and then as a score of violent Sunni insurrections from sub-Saharan Africa to the Philippines, but most prominently in the Arab Middle East. The neocons were intent on constructing an alternative model in the region, not on acquiring an American colony.

Whatever Bush and Cheney claimed – and they said many untrue and stupid things, such as that Saddam Hussein was involved in 9/11, and had the mythical weapons of mass destruction – the neocon choice of Iraq was because it looked to be the country most likely to embrace radical change. It had the most hated government and there was a large enough section of the population that could be expected to support overthrowing the Baathists that it was hoped that a new regime could showcase Western democracy to act as an alternative regional pole to radical Islam and Baathism. For such an effort it was probably better to choose a regime that was not explicitly Islamic, as that might blunt the reaction that the U.S., already deep in the war in Afghanistan, was embarked on a war against Islam as a whole.

While they were not entirely wrong, the neocons underestimated the tenacity of the Baathists, as well as the extent to which the widespread Islamic radicalism had coalesced around the traditional Quranic injunction to spread Islam by force throughout the world. This had already acquired thousands of battle hardened fighters ready to swing into action on any front that provided them an opportunity to further their cause. The neocons overestimated the organizational capacities of the atomized Shia population, the inevitable hatreds they harbored toward their long-time oppressors that would make it difficult for them to act inclusively toward the Sunnis while there was still a considerable Sunni force engaged in killing Shiites, and the general absence of a democratic political tradition in the country. And above all, as with most Western liberals, they could not believe that Islam in its mutually hostile camps could be a more powerful force than the promise of political liberty.

What About the Oil?

It is an article of liberal faith that the U.S. invasion of Iraq was to seize the country’s oil. And not only liberals say this. Many leading Republicans do as well. Alan Greenspan, a long-time Republican and chairman of the Federal Reserve (1987-2006), in a much quoted comment in his 2007 memoir, The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World, said, “I am saddened that it is politically inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil.”

Current U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, Republican Senator from Nebraska, 1997-2009, and an untypical Republican critic of the war, in 2007 declaimed:

“People say we’re not fighting for oil. Of course we are. They talk about America’s national interest. What the hell do you think they’re talking about? We’re not there for figs.”

And there is considerable truth to this opinion. Under Saddam, oil, as in other major producers Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Mexico, was nationalized. Venezuela has state dominance with minority shares for private companies. Russia privatized after the fall of the Soviet Union but the state has reabsorbed a large part of the oil industry. In the United States, Libya, and Nigeria oil is owned by private companies. The U.S. did in fact successfully pressure the Maliki government to privatize Iraqi oil.

The first contract bidding by private companies took place in 2009; Exxon and Occidental were among the bidders. The final arrangement specified that the Iraqi state retained a permanent 25% interest in all of its oil properties. The sections that were leased to private companies that year were valued at $5.86 billion. Of that, two contracts out of 23 went to U.S. firms: Exxon and Occidental, for a combined total of $1.17 billion, or 20%. China secured contracts worth $1.12 billion, and Russia $669 million. Contracts worth more than $100 million also went to Shell (Netherlands), BP (mostly British), ENI (Italy), and Angola, South Korea, and Malaysia.

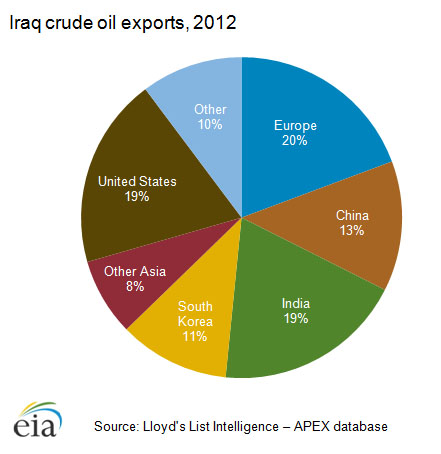

Sales of the oil itself, as with the contracts to produce it, revealed the same pattern (see pie chart). Only 19% in 2012 went to the United States, while 51% of Iraqi oil was sold to China, India, and other Asian countries, 20% to Europe, and 10% to others. (U.S. Energy Information Administration data, 2012)

One reason the U.S. came in so far behind the Asian and Russian bidders was because the terms Iraq offered were well below what other oil producing countries offered. Privately owned oil companies like Exxon have to sell their oil at the world market price. Iraq, instead of offering its contract bidders a steep discount from the world price offered a take-it-or-leave it $1.40 a barrel. That simply wasn’t enough for privately owned companies to show a profit, pay dividends, high salaries, and contribute to their recently skyrocketing R&D costs. State-owned companies had no such problems. Their governments paid separately for R&D and all they expected from Iraq was oil at world market prices. This put all countries without state-owned oil monopolies at an insurmountable obstacle, the United States included. The New York Times commented:

“Before the invasion, Iraq’s oil industry was sputtering, largely walled off from world markets by international sanctions against the government of Saddam Hussein, so his overthrow always carried the promise of renewed access to the country’s immense reserves. Chinese state-owned companies seized the opportunity, pouring more than $2 billion a year and hundreds of workers into Iraq, and just as important, showing a willingness to play by the new Iraqi government’s rules and to accept lower profits to win contracts. ‘We lost out,’ said Michael Makovsky, a former Defense Department official in the Bush administration who worked on Iraq oil policy (June 2, 2013).

This came to a head four years after Iraq’s first open bidding. The Financial Times reported:

“When Iraq held its first postwar oil licensing round in June 2009, groups like ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell and BP flocked to Baghdad for what was one of the most eagerly anticipated events in the oil industry calendar. At the fourth round last May, none of them bid” (March 17, 2013).

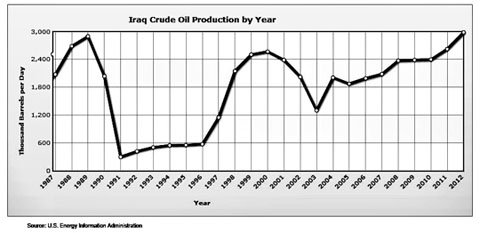

Interestingly for the notion that Iraq simply fell apart during the long years of war after 2003, Iraq’s oil production fell far lower as a result of the First Gulf War following Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait. And by 2012, output was higher than it had ever been under the Baathists.

Lucrative contracts for drilling and maintenance did go to Dick Cheney’s old firm, Halliburton, and to Baker Hughes, another American company, as well as to Weatherford International (Switzerland) and Schlumberger (Paris). These services will be paid many billions for their work, but will not take away any oil. Halliburton will become richer but it won’t power any American cars.

So the U.S. has settled for second best: keeping Iraqi oil as part of the global supply so that prices don’t go up the $30 to $50 a barrel they might rise if no oil was produced there. Andrei Kuzyaev, president of Lukoil Overseas, in a 2011 interview, said, “The strategic interest of the United States is in new oil supplies arriving on the world market, to lower prices” (New York Times, June 14, 2011). Recall that the huge subsidies to Saddam from both communist and capitalist countries while he was gassing Iranian troops in the 1980s was in important part because it was thought he was less likely to withhold oil from the world market than the Islamic Republic. After his invasion of Kuwait, Saddam looked equally dangerous as the Iranian mullahs.

This brings us to the role of oil in today’s world.

Criticisms of the American government’s fixation on securing supplies of oil are peculiarly otherworldly unless they are tied to a call to retrofit the economy to run on alternative sources of energy. The reality, and this is an unpleasant topic for many people, is that our world society has been built on a historically brief use of a once-in-a-lifetime nonrenewable energy bonanza. And at this time no country can do without it, or even suffer any significant diminution of its supply, without facing a crisis and potential social collapse.

From the coal that fueled Britain’s industrial revolution that began around 1760 to the kerosene that replaced whale oil in our lamps at the end of the nineteenth century to the gasoline that ran our cars and aeroplanes in the twentieth, these are the rapidly depleting remains of plants and animals that died many tens of millions of years ago and represent a one-time gift of a huge energy boost compared to all other currently available energy sources.

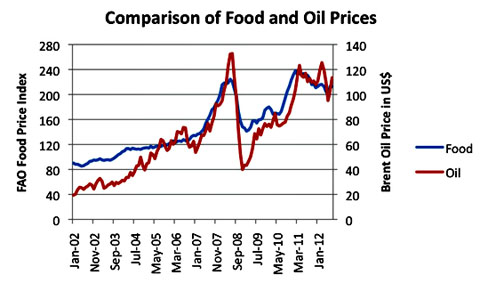

The turmoil now roiling Iraq and Syria is part of the crisis that began in 2010 with the Arab Spring. Dictators that had been tolerated for generations became unbearable when food prices, which closely track oil, began to rise in 2002, had almost tripled at the time of the oil price spike in 2008, and did triple the 2002 rate in 2010. Oil for transportation, powering farm equipment, and fertilizers is so central to food production that their prices move in lockstep, and oil prices increased drastically when conventional crude topped out in 2005 and prices began to be set by fracked oil and Canadian tar sands.

This has had a disastrous effect on the stability of poor nations, most particularly in the Mid East, even among large oil producers except places like Saudi Arabia that provide large popular subsidies to defuse discontent. The eastern Mediterranean and North Africa are particularly vulnerable to the global ecological downward spiral of rising oil and food prices, combined with limited water and arable land, in a part of the planet with some of the highest birth rates. This is a situation that induces desperation far deeper than politics or religion, but which impels people to seek salvation in the faith they know, in this region, Islam. And some of those religious leaders are fanatics who promise prosperity in a new holy war.

More broadly for all of our futures, the greatest, and potentially fatal, dereliction of our governments, Democratic and Republican alike in the United States, but of every other significant government in the world, capitalist or communist, has been to imagine that they can just go on indefinitely with perpetual geometric growth – of population, in the consumption of mineral and oil resources, of supplies of ocean fish, of arable farmland, of potable water – without encountering the collapse of populations that every other species has met when its expanding numbers outran its food resources. The persistent efforts to manipulate the governments of the Middle East, sometimes to the benefit of their peoples and more often merely an accommodation with their dictators, has been little more than buying time, time that has been wasted looking to protect sources of liquid hydrocarbons that will become more and more scarce instead of making massive investments in alternative energy sources. This threatens the viability of economies throughout the planet.

Though peak oil, predicted for shortly after the turn of the millennium, has been late arriving, there are a growing number of ominous signs. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s data, world oil production grew from 66.44 million barrels a day (mb/d) in 1990 to 83.16 mb/d in 2004, an annual growth rate of 1.62%. In the eight years since, the rate has been halved, to .82%, and that includes the much vaunted boost from fracked oil in North Dakota and Texas. BP, in its authoritative Statistical Review of World Energy 2014 issued this June, reported that world production in 2013 increased by a mere 560,000 mb/d while consumption grew by almost three times that amount, at 1.4 mb/d. Oil was selling for $12 a barrel in 1998 ($17 allowing for inflation) and has been $100 or better for several years. On June 24, West Texas Intermediate, used in the U.S. Midwest, was selling for $106, with the European Brent price, which is also used on the American coasts, at $114. A major cause was the peaking of conventional crude in 2005, which has since been supplemented by far more expensive unconventional sources, including fracking, deep sea, and Canadian tar sends. These high energy prices were a major contributor to the deep world recession that began in 2008 and is not fully over yet.

Conventional oil worldwide is depleting at 3-4% a year. The privately owned international oil companies in the last 10 years spent $3.5 trillion trying to increase the flow of conventional oil They failed utterly and got nothing for their money. They spent an additional $500 million on unconventional sources. Pretty much all of them are cutting back drastically on conventional investments. But fracked wells, which are now just able to make up for conventional oil depletion, themselves have a far more rapid depletion rate than conventional wells: for each new well some 85% of its lifetime output is exhausted by the end of the second year.

This explains why governments worldwide are more and more concerned to locate and put a lock on the oil needed to keep their economies running. In the United States the Republicans, heavily compromised by campaign financing from the big oil companies, are doing everything they can to thwart investment in alternative energies.

Even if that were not so, while electricity can be produced by wind, solar, and natural gas, electricity can’t fuel airplanes, or, at this stage, cross country trucking or automobiles that must cover many miles. Without a massive reorientation to produce as much energy as possible from sources other than fossil fuels all countries except those few with very large oil reserves are headed toward resource wars that will threaten the fabric of our civilization.

ISIS and the Islamic World Revolution

ISIS, more properly the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, is one of scores of Sunni Islamic organizations that, in many countries, have taken up the banner of jihad, to, as they see it, resume the military expansion of Islam that began under Muhammad in the seventh century. Those in the Middle East and North Africa – their cothinkers exist and have led bloody struggles, in Nigeria, the Philippines, Thailand, Chechnya, and other places outside of the Arab-Persian region – fight in the name of Allah to wrest power from Shias and Sunnis alike who do not profess their own severe and intolerant brand of Islam. Their tactic, evolved over many years, is extreme terror: the slaughter of civilians, beheadings, crucifixions, suicide bombings in markets and hotels, mass executions.

ISIS and its similars are masters of terror, but it is a mistake to call them mere terrorists. Genghis Khan left piles of skulls wherever his horsemen rode as they thundered out of Mongolia, subjugating an empire that ranged from Peking and Lhasa in the east to Moscow and Baghdad in the west. Three of the khanates Genghis’s armies established embraced Islam. Modern day Islamists have adopted his ruthless methods of battle. Unlike the Mongols, who after winning were tolerant of all religions, the Islamicist radicals are intolerant in the extreme.

The Islamic radicals view Western secularism and democracy as repugnant godless paganism, and Muslim collaborators with the West, such as the corrupt Saudis, despite their Wahhabi pretensions, as traitors to the faith. All are rejected as jahiliyyah, literally the state of chaos in Arabia before the coming of Islam, but in practice meaning degenerate barbarism. Their most essential belief is that all valid law is the law dictated by Allah in the Quran and all human-made laws that conflict with God’s law are an abomination to be abolished.

The most insightful short piece I have seen on ISIS is an interview with Olivier Roy in the June 16, 2014, New Republic. Roy is a well-known French authority on Islam who now teaches at the European University Institute of Florence, Italy. Roy is anything but an Islamophobe. He has written widely on the ways in which orthodox Muslim believers can coexist in Western secular societies and sharply criticized those who regard Islam as inassimilable in Europe.

The main points Roy makes about ISIS, after establishing that its origins are in Al Qaeda, is that it is a “globalized international movement which is lacking deep roots in the local society and which does not have a ‘national’ project (contrary to Hamas, Hezbollah, Palestinian Jihad, or the Shia radical movements).” It draws on an international radical Islamic movement that has grown up over many years and in many countries, beginning shortly after World War II. Roy says that many of its foreign volunteers don’t speak Arabic and have little interest in local Iraqi society apart from imposing Sharia law.

The London Daily Mail online website on June 14 offered its estimate that ISIS had about 12,000 fighters in Iraq and Syria of whom 3,000 were from others areas, 500 from Europe and 2,500 from Pakistan, Chechnya and other places relatively distant.

Paul Berman, in the June 16, New Republic, wrote of ISIS that its “universal goals confer on it the ability to summon supporters from around the world. This we have seen before. During the last few decades, the perfect society of the seventh century has repeatedly gone into bloom, whenever some part of the Muslim world has fallen into chaos: in post-Soviet Afghanistan; in Sudan; in parts of Iraq after the overthrow of Saddam; in Yemen during a period of turmoil; in northern Mali during a civil war; and in parts of Syria. To watch it sprouting up yet again ought not to shock us. . . . And, in each case, the seventh century has blossomed because, no matter how few and marginal may be its champions in any given country, their comrades in other parts of the world, the knights of jihad, can be counted on to volunteer their services. They rush to enlist because they are waging a sort of world war on a protracted basis, and they know they are doing so – and their lucidity on this point gives them an advantage over some of their foggy-headed enemies.”

In Olivier Roy’s view, ISIS is neither a political party nor a social movement and is ill-fitted to transform its army of militants into such things. Its ideology is of global conquest for Islam. He predicts, as have many others since, that while ISIS may hold the Sunni areas of the two countries it spans, it will not penetrate further into Iraq but will be stopped by the Kurdish Peshmerga in the north and by the Shia under the leadership of the clergy, quite independent of what Maliki’s formal army is able to do. He also predicted that “tensions between Jihadis, Baathists and tribal leaders will erupt among Sunnis.” He believes the result will be a weak central government with three autonomous regions or a splintering of Iraq into its three component parts.

The Sunni-Shia division, he says, was not sharp in the twentieth century until the Islamic Revolution in Iran, which provoked a counter movement by the Sunni powers, led by Saudi Arabia. While the Shia have a clear bloc, led by Iran, that includes Assad in Syria and Hezbollah in Lebanon, plus a weaker link to Maliki in Iraq, “the Sunni front is utterly divided and has no common objectives.” Apart from opening the road to Kurdish independence, the main effect of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, he said, was the destruction of “the main Sunni bulwark against Iran.” So what was good for the Kurds was bad for the Saudis.

Roy also agrees with many other observers, including an op-ed in the June 24 Los Angeles Times by Dennis Ross, a Middle East advisor to both presidents Clinton and Obama, that Obama’s failure to act early in the Syrian civil war to bolster more moderate rebels makes any intervention now, after ISIS has established itself over a wide swath of both countries, more than difficult.

Islam began as a religion of conquest and the jihadis of today regard themselves as the continuators of that glorious heritage, first and foremost to recover all of the territories once ruled by Islam and since lost. The armies of Muhammad and his successors swept out of Arabia in the seventh century and rapidly took all of the Middle East and North Africa. Muslims ruled Spain from 711 to 1492. The Muslim Ottoman Turks laid siege to Vienna twice, in 1485 and 1683, ruled Greece from the mid-15th century until 1821, controlled central and southern Hungary, 1546-1699; Bulgaria, mid-1300s to 1878; and Albania, 1385-1912. Today’s Islamists openly declare that they want all of that back. They also often cite a Quranic prophecy that Islam will conquer and rule in Rome.

So what are the limits of ISIS’s territorial ambitions? The name it has chosen, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, suggests its regional reach. It is sometimes rendered in English as the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria. Al-Sham does mean Greater Syria, but it was a designation under the Ottoman Empire before the current states of Syria and Iraq existed. Greater Syria, or al-Sham, under the Ottomans was a synonym for the Syrian vilayet. It included what are now Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, and Israel, and encompassed a piece of southern Turkey and Alexandria in Egypt.

At this time ISIS is the most successful Sunni jihadi organization in the last hundred years. The mainstream press, in a sign that they have not quite caught up to the reality, continue to describe it as an Al Qaeda splinter group. This is a bit like calling Lenin’s Bolsheviks a Social Democratic splinter group. Like the Bolsheviks, the Islamic revolutionary movement in its Middle Eastern and North African theatre, seem to have a minimum and maximum program. Its first objective is its own reconquista, of all of the territories once occupied in the first wave of Islamic expansion. This is often expressed in jihadi writings and videos as “Not one inch that was once Muslim shall remain in infidel hands.”

Several websites of ISIS supporters have posted maps that they claim are ISIS’s five-year goal. I don’t know if this should be taken seriously, but they show ISIS’s black banner over the whole of the Middle East as far east as Kazakhstan, sweeping all of North Africa as far west as Morocco, and swallowing up India and Indonesia. A few even include Spain, once a Muslim colony. Grandiose fantasies indeed, unless ISIS’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, should prove to be a new Genghis Khan. His ambitions are plain in this nomme de guerre he has chosen, calling himself by the name of the first Sunni caliph. Al Jazeera on June 29 reported the ISIS has declared the creation of its caliphate with its initial boundaries stretching from Diyala province in eastern Iraq to Aleppo in western Syria. Not unexpectedly, they named Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as caliph and demanded that all Muslims recognize him as their supreme leader. It has now changed its name to just the Islamic State, an entitle that in principle has no boundaries but aims to encompass all Muslims, and to spread Islam to the places where it is not now dominant.

Pledges to establish a caliphate that reconquers the whole of the Muslim Middle East and North Africa are common among Islamic radicals, though this is the first time that one has been created in a part of that vast land. Expanding that to Spain, or still further, Europe and the Americas, are not at all rare.

A video posted to the internet May 14, 2014, in which a Kosovo volunteer fighting with ISIS in Iraq harangues his comrades, gives a good flavor of the sentiments and thinking of this group:

“We bless Allah who has enabled us to pledge allegiance to the Emir of the Believers, Abu Bakr Al-Qurayshi Al-Baghdadi. Oh our Emir, we have pledged to obey you, we have pledged to die. Lead us to wherever Allah commands you. To the tyrants and infidels wherever they may be, we say the same thing that Abraham said to his father: ‘Indeed, we disassociate ourselves from you, and from whatever you worship other than Allah. We have renounced you, and between you and us, eternal animosity and hatred have appeared, until you believe in Allah alone.’ We say to you, as the Prophet Muhammad said: ‘We have brought slaughter upon you.’ Know this, oh infidels: By Allah, we shall cleanse the Arabian Peninsula of you, you filth. [waving a long knife] We shall conquer Jerusalem from you, oh Jews! We shall conquer Rome and Andalusia, Allah willing. – say ‘Allah Akbar!’ Allah Akbar! – say ‘Allah Akbar!’ Allah Akbar! These are your passports, oh tyrants all over the world. By Allah, we are Muslims! We are Muslims! We are Muslims!”

The video was translated by MEMRI, the Middle East Media Research Institute, and posted to YouTube. I have supplied the link for readers who want to watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zIxY8thehL8

Following are the text of two other YouTube videos from different parts of the region.

First, Sheik Ali Al-Faqir, formerly Minister of Religious Endowment in Jordon’s government, usually seen as a moderate Arab regime, in a May 1, 2008, broadcast on Al-Aqsa TV (Hamas-Gaza):

“We must proclaim that Palestine from the (Jordan) River to the (Mediterranean) Sea is an Islamic land, and that Spain – Andalusia – is also the land of Islam. Islamic lands that were occupied by their enemies will once again become Islamic. Furthermore, we will reach beyond these countries, which were lost at one point. We proclaim that we will conquer Rome, like Constantinople was conquered once, and as it will be conquered again. – Allah willing. We will rule the world, as has been said by the Prophet Muhammad.” (memritv.org https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aYDfACr-y4s )

The next one is from an April 11, 2008, sermon by Yunis Al Astal, a preacher and Hamas member of the Palestinian Legislative Council for the area of Khan Yunis. It is interesting because it puts in question the common perception that Hamas, radical as it may be, is concerned solely with eliminating the Israeli Jews and seizing the land that is now Israel. Al Astal declares to his audience:

“Allah has chosen you for Himself and for His religion, so that you will serve as the engine pulling this nation to the phase of succession, security, and consolidation of power, and even to conquests thorough da’wa [summoning to Islam, proselytizing] and military conquests of the capitals of the entire world. Very soon, Allah willing, Rome will be conquered, just like Constantinople was, as was prophesized by our Prophet Muhammad. Today, Rome is the capital of the Catholics, or the Crusader capital, which has declared its hostility to Islam, and has planted the brothers of apes and pigs in Palestine in order to prevent the reawakening of Islam – this capital of theirs will be an advanced post for the Islamic conquests, which will spread through Europe in its entirety, and then will turn to the two Americas, and even Eastern Europe. I believe that our children or our grandchildren will inherit our Jihad and our sacrifices, and Allah willing, the commanders of the conquest will come from among them.” Al-Aqsa TV (Hamas/Gaza). Watch at: http://www.memritv.org/clip/en/1739.htm

Though Islam, Christianity, and Judaism are all Abrahamic religions, deriving from ancient Judaism, Islam differs from its two collateral branches in important ways. Christianity had to abandon control of the state by religious authorities at the time of the Reformation and the Thirty Years War. Jews, after reestablishing their state in Israel in 1948, favor Judaism but include 20 percent of their population who are Muslims, others who are Christians, and a broad variety of Jewish denominations and sects. In contrast, Islam has never agreed to the separation of mosque and state, and views all non-Muslim regimes – and many ruled by Muslims who appear corrupt or heretical – as in violation of Allah’s laws. The Arab, Persian, and Turkish states purged virtually all of their Jews after 1945, while Saudi Arabia permits no churches or public worship of any religion but Islam. The Islamic Republic of Iran by its constitution does not permit non-Muslims to be elected to representative bodies. Algeria after their revolution against France adopted a constitution in which citizenship was restricted to Muslims.

Islam retains in Sharia law practices that are barbaric by the standards of most other nations but are widely believed by Muslims to be the required will of Allah. Some of these have their origin in ancient Jewish law as recorded in Deuteronomy, such as stoning to death adulterers (in today’s Islamic world this usually means only the women, including the victims of rape) and homosexuals. These practices were abandoned by the Jews thousands of years ago and were never revived by Christianity, despite the large numbers of Americans who proclaim themselves believers in biblical inerrancy.

Muhammad added other draconian punishments: chopping off of hands for theft, and the death penalty for renouncing Islam, even if you were merely born into it and were never a believer. Support for these laws remains extraordinarily widespread in Muslim countries, and as this is believed to be the will of Allah, the jihadi movement’s championing of Sharia finds broad, at least tacit, support, though its practitioners are often rejected because of other aspects of their brutal rule. Below are the results of a Pew Research survey of Muslim support for Sharia published in 2013. I have extracted only the countries close to Iraq. Because of the civil war in Syria the survey could not be taken there. Lebanon, with not only both Shiites and Sunnis but a large Christian minority, is the more tolerant outlier.

|

Muslim Beliefs About Sharia |

||||||

|

Extracted from Pew Research survey, April 30, 2013 |

||||||

|

Percent saying yes |

||||||

|

|

Iraq |

Afghanistan |

Jordan |

Egypt |

Palestinian |

Lebanon |

|

Sharia is the revealed word of God |

69 |

73 |

81 |

75 |

75 |

49 |

|

Sharia should be the law of the land* |

91 |

99 |

71 |

74 |

89 |

29 |

|

Apply to Muslims and non-Muslims |

38 |

61 |

58 |

74 |

44 |

48 |

|

Approve Sharia punishments for theft** |

56 |

81 |

57 |

70 |

76 |

50 |

|

Should stone to death for adultery*** |

58 |

85 |

67 |

81 |

84 |

46 |

|

Death penalty for leaving Islam |

42 |

79 |

82 |

86 |

66 |

46 |

|

*All questions after this are only asked to Muslims who said they wanted Sharia law. **Flogging and cutting off hands. ***Includes homosexuality |

||||||

The survey does not break down the Iraq respondents by ethnicity or confession. The Kurds in their autonomous region where they can act as they wish toward Sharia have not been known for extremism. Nor have the Shia majority in Iraq. This may be reflected in lower support for the more extreme punishments compared to Afghans, Jordanians, Egyptians, and Palestinians.

ISIS built its current forces in the hinterlands of Syria. It has had some militants in Iraq continuously since the early days of the U.S. invasion. Its principal founder, the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, went from Amman to Afghanistan in 1989 where he met Osama bin Laden just as the Soviets were withdrawing. He then went to Europe, where he founded an Islamic group dedicated to overthrowing the Jordanian monarchy. Returning to Jordan, he was arrested when guns and explosives were found in his house and spent six years in prison. Released in 1999, he masterminded a failed attempt to blow up the Radisson Hotel in Amman. He fled to Afghanistan, but after the U.S. overthrow of the Taliban in 2001 he went to Iran, and from there to Iraq. He organized the assassination of American diplomat Laurence Foley.

During 2003 Zarqawi’s group carried out bombings in Casablanca, Morocco, and Istanbul, Turkey. In 2004 he orchestrated an ambitious but intercepted attempt to use 20 tons of chemicals, including nerve gas, to attack Jordanian government officials and the U.S. embassy. His Al Qaeda in Iraq killed thousands. It released videos of Zarqawi personally beheading two American civilians. After Zarqawi was killed in 2006 the group was severely reduced in Iraq but always retained some strength there, while rebuilding its forces across the border in Syria after that civil war began.

Though Al Qaeda in Iraq appears to be its principal component, ISIS is actually a fusion of several jihadi organizations. This includes the Mujahideen Shura Council, the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), Jaysh al-Fatiheen, Jund al-Sahaba, and several others.

In January 2014, ISIS captured Fallujah, 43 miles west of Baghdad. By the time of its assault on Mosul in early June it had concluded alliances with former Baathist organizations and some Sunni tribal leaders. Just a few months back, the original Al Qaeda – headed after Osama’s death by Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Egyptian physician who long ago set aside his Hippocratic oath to “never do harm to anyone” – dissociated itself from ISIS. Its beheadings and mass killings were too much even for one of the world’s most notorious jihadi centers. When Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in Syria last fall announced that ISIS was merging with the official Al Qaeda Syrian affiliate, the al-Nusra Front, al-Zawahiri quickly denied it. Al-Nusra then even fought some pitched battles with ISIS. On June 25, 2014, however, a section of the al-Nusra Front announced that they had changed their minds and were joining ISIS. It reminds one a bit of Napoleon’s escape from Elba. The Paris papers proclaimed, “The Beast Has Landed!” By the time he reached the city the headlines were, “The Emperor Has Returned!”

Where Things Stand Now

On the government side, Maliki at this writing shows only minimal signs of heeding calls to broaden his government, though new emergency elections have taken place and a new government is about to be formed. The large Sunni forces that were key to routing the Baathist and Islamicist insurgency in the Sunni heartland of Anbar province during the surge in 2007 now are standing on the sidelines. Some are being hunted by ISIS, which carries a grudge from those old battles. A few have gone over to ISIS. But most, though they fear and hate ISIS, refuse to fight for Maliki, who has not only excluded these ex-Baathists who fought on the American side during the surge, but has jailed scores of them and held them for years without trial.

The old Iraq is dead. The question is whether it will split into two parts or three, with three more probable. The prison house gates were opened by the American invasion in 2003. The Kurds and Shias broke out. The Kurds have gone their own way, while the Shiites sought to build a new national regime, principally in their own hands. Despite the collapse of the national army when asked to fight a Sunni advance in a Sunni area, the story should be different in the Shiite heartland. It seems likely that ISIS will fail to take Baghdad and the Shiite south, especially as Iran already has advisers from their Revolutionary Guards on the scene.

Iraq’s Sunni tribes and even Saddam’s former Baathists will come to regret their devil’s bargain with ISIS. Under leaders who almost casually shoot a thousand prisoners at a time or behead their critics rather than argue with them, it will prove harder to get out than in. There is certainly a good chance that ISIS will succeed in establishing a new state spanning the borders of existing Iraq and Syria. Even their dream of a new warlike and totalitarian caliphate could spread further. A lot depends on the ties they are able build with the Sunni masses, most of whom share a belief in even the most brutal provisions of Sharia. There are already reports of demonstrations in support of ISIS in Britain, Australia, Jordan, Libya, and Pakistan, while in India a Shiite Muslim organization claims to have recruited 100,000 volunteers to fight on the other side. We will see how real old Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations thesis proves to be.

That leaves unanswered what the United States should do about Iraq now. The most important starting point is that, for all its superficial appearance as a mere continuance of the previous war, it is a different situation, one in which America has only the most limited options. It is reasonable to fear the establishment of a jihadi state, but only a massive intervention on the ground could head that off now, especially as ISIS can at will retreat into Syria. The U.S. has lived before with totalitarian enemies bent on its destruction without going to war with them. The situation has years to play out before America can fully take the measure of this opponent.

As the Kurds depart, and most of the Sunni territory falls under the control of ISIS, what remains is a Shiite state with a very reduced Sunni minority. Only a massive intervention by Iran would change that alignment and it is hard to see Iran’s interest in retaking the troublesome Sunni parts of Iraq. The U.S. should not take part in that battle. Even if the Baghdad government now invites Sunni participation at all levels that is not going to make ISIS go away or relinquish the territory it holds. At best the United States can provide minimal help to Baghdad if ISIS proves to be stronger than it looks and drives deep into the Shiite lands. That seems an unlikely variant, and America should not take part in a confessional civil war if Baghdad tries to retake Anbar province.

This has become a regional battle by proxy between the Shia and Sunni powers, Iran and Saudi Arabia, with ISIS as an uncontrollable force in its own right nominally on the Sunni side. Any significant intervention now becomes taking sides in a regional battle far beyond America’s capacity to resolve and where identification with either side will have unwanted consequences for relations with the other side.