A SOUTHERN VOICE FOR THE AGES

By Bob Vickrey

When his literary agent once asked best-selling writer Pat Conroy why there was not more sex included in his novels, he responded quickly, “Because my grandmother is still alive.”

When he tells that story at writing seminars and on the banquet circuit, there is always an eruption of laughter and applause in the room. Everyone in attendance fully understands the precarious minefield a writer navigates when it comes to family matters.

He has traditionally offered a serious challenge to young writers, however, as he encourages them to “be bold” and tell their stories courageously without worrying about who is in the audience.

After more than four decades of writing, there are legions of Conroy’s loyal fans who would attest to the boldness of his work—not to mention his passionate style and his consummate storytelling skills.

Pat Conroy’s interest in writing started early in life as his mom read stories to him and his siblings when they were growing up. He inherited his gift naturally as he followed in the great Southern storytelling tradition of Faulkner, Wolfe, Fitzgerald, and Welty. He is one in a long line of second generation writers to carry on the Southern style. Walker Percy, Dorothy Allison, Reynolds Price, Anne Rivers Siddons, and Ferrol Sams have all made their mark in continuing that long tradition of storytelling about a region that has produced writers as one of its most precious exportable commodities.

His lyrical and descriptive writing style is indeed a throw-back to the fashion of that earlier era which had provided him with his strongest influences. The vivid word-portraits he paints in his imaginatively evocative passages are truly rare in contemporary literature. In fact, Eugene Norris, his high school English teacher and influential early mentor, worried about Pat’s obsession with the works of Thomas Wolfe. Norris thought Conroy should find his own voice and not be seduced by the singular style of Wolfe. Conroy once said, “For many of those early years, I could likely have been sued by the estate of Thomas Wolfe for plagiarism.”

Conroy’s first foray into writing started when he was a student at The Citadel where he completed a book entitled, The Boo, about his commanding officer, Colonel Thomas Nugent Corvoisie, whom he had greatly admired while serving as a cadet. When he presented his finished offering to the cigar-chomping, brusque Colonel, they both decided the book needed a good publisher. Therefore, with their limited knowledge of all things regarding book publishing, they consulted, what else?—the Yellow Pages. Flipping quickly through the pages, the Colonel found listings under the heading of printing for business cards, invitations, and finally, there it was—books.

They made the call to the local printer and discovered that for $2,000, they could have 500 copies printed of The Boo. Pat told the Colonel that he knew a Citadel graduate named Willie Sheppard who worked at the Bank of Beaufort in his hometown in South Carolina , and was quite sure that Willie would loan him the money. They were both suddenly thrilled at the prospect of seeing the finished book. Thus—the rather inauspicious, but nevertheless, creative entrepreneurial genesis of Conroy’s first book.

After he had completed The Water is Wide, Conroy hired a literary agent named Julian Bach in New York , whom he always referred to as “my pretentiously named agent.” His new book was about his year spent teaching impoverished black students on Daufuskie Island , just off the South Carolina coast. Julian called one day and excitedly told Pat, “Houghton Mifflin wants to publish the book. That’s not all! Are you ready for this? Seventy-five hundred dollars!” Pat mulled over the amount for a moment and finally told Bach, “I don’t think Willie Sheppard is going to lend me that much money.”

Conroy may have confused his facts about publishing that day, but he was certainly off to a good start in his long writing career. The Water is Wide was published in 1972, and had modest, but respectable sales. A short time later, a Hollywood producer called and wanted to make a movie out of the book and had already tentatively cast actor Jon Voight to play the role of Pat.

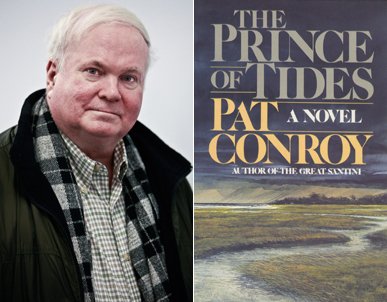

The Great Santini, a not-so-flattering portrayal of his Marine fighter pilot father, was published in 1976, and was greeted by positive reviews and followed by considerably better sales than the previous book. Santini was a fictionalized chronicle of the tumultuous Conroy family household as it endured the tyrannical behavior of a father who ran his home life in the same military style he was accustomed to living at his air base.

Before the book had been published, Pat had anxiously returned home the previous year to present the finished manuscript to his father. After his dad had read only a few pages of his unflattering portrayal in the book, he threw the pages of the manuscript wildly across the room, declaring it “total and utter garbage.”

A turbulent period ensued as members of the family each had qualms about their private lives becoming public with the forthcoming publication of the book. However, when Pat broke the news to them that the screenplay had been sold and a Hollywood film would be made about their story, the atmosphere changed drastically. Every member of the family suddenly became totally enamored with the casting of the movie version and which actor should be chosen to play each one of them.

Suddenly, the mood changed, and there was excitement throughout the entire Conroy family in South Carolina . Pat’s father, Donald, was already thinking of actors who might be perfect to play his role as “The Great Santini.” Pat called him a few weeks later, knowing that Robert Duvall had already landed the role, and said, “Dad, you’re going to be thrilled at the casting. They’ve selected Don Knotts for your part in the movie.”

While Conroy had enjoyed a fleeting “honeymoon” relationship with Hollywood life, his real love had always been writing, and the entertainment business occasionally sidetracked him in that mission. He wasn’t the first Southern writer to have fallen under the spell of the lights of Tinsel Town . He had good company in earlier years when his same heroes, Faulkner, Wolfe, and Fitzgerald had spent an inordinate amount of time eating and drinking at the Musso and Frank Grill in Hollywood while discussing their next movie project.

Pat and I were introduced in Boston when I first joined the publishing firm of Houghton Mifflin. The Water is Wide had just been published and he was visiting his editor and publicist. We went to dinner that evening and talked about how we both had landed in our various roles with Houghton—he, as a struggling writer, and I, as a fledgling publisher’s representative who would be promoting his book in my Southwestern territory.

Our bond was formed of both a new friendship, as well as a total naïveté at what lay ahead of us in our futures. We somehow knew instinctively, even then, how little we understood about the larger world. I made the observation that evening that this represented the first time someone had paid him to write and someone had paid me to read. He responded quickly, “Yea, but not very much!”

The first book tour that brought him to Texas was when he was promoting The Great Santini. I picked him up at the Dallas /Ft. Worth airport and we headed off to do numerous interviews with newspapers and local afternoon talk shows in the Metroplex area. He was well prepared for the shows, even if his interviewers and television hosts were not. He often put the ill-prepared hosts at ease and offered them easy questions that would expedite and ease the interview process.

We spent a lot of “car time” on our first book tour together as we traveled across the wide open spaces of Texas . I think Pat would agree that we did a pretty feeble job of harmonizing on Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys’ tunes. When we arrived at the local CBS affiliate in Dallas, Pat had been booked on the same afternoon talk show with—none other than—“Brother” Al Richmond—the original pianist for Bob Wills and his famous Texas Playboys. We tried to explain to him how we had traveled for days singing his tunes, but somehow we realized that Brother Al never truly understood the significance of our spontaneous rendezvous on that lucky day.

When the manuscript of The Prince of Tides first arrived on my doorstep in California in 1986, it was so heavy that I thought I’d need the postman’s help in transporting it into my house. I knew that Pat had been busy working on the novel that would ultimately transform him into the publishing star he was destined to become, but I wasn’t quite ready for the force and power that his new work would deliver for me on such a personal level. I read that night into the early morning hours and reluctantly put the rest of the bulking stack of pages aside until the following day.

The story had mesmerized me like few other books had, and I knew at once that Pat had written his definitive work, and had also successfully exorcised many of the demons of his youth in writing this brilliant ode to family. But perhaps even more importantly, it likely had provided his ultimate liberation from a tumultuous family history.

The company’s initial launch for The Prince of Tides was planned for the annual American Booksellers Association meeting in New Orleans that same spring. With an October publication date set, Houghton Mifflin distributed more than 1,000 copies of the advance readers editions at the downtown Convention Center. The inevitable “buzz” of the 25,000 booksellers, authors, and publishers assembled there was in strong evidence by the end of the second day. Conroy was suddenly the man of the hour.

The weekend culminated during a huge breakfast gathering, featuring guest speakers: legendary newsman Walter Cronkite, comedienne Carol Burnett, and Conroy. Tickets had been at a premium for the event. Cronkite spoke about his new book, North by Northeast, (co-authored with Ray Ellis) during the opening portion of the program, and also served as master of ceremonies.

His eloquent and adoring introduction of Conroy left the author a bit dazed by the time he took center stage. Cronkite said, “It must be a good feeling to be able to string together those beautiful lovely words in a necklace of incomparable prose.” He declared his envy of Conroy’s gift of storytelling, but suggested that Pat had been born with a distinctive advantage of “having been blessed with an Irish muse.”

Of course, Cronkite’s rich, mellifluous voice added to the dramatic introduction as well. When Pat began, he looked out at the crowded room and simply said, “After being forced to follow Walter Cronkite on the program, my voice must sound like that of a parakeet in comparison.”

Pat proceeded to deliver a speech that booksellers talked about for years in the future. He had his audience laughing after he told them the story of the ill-conceived publishing plan of The Boo, and then regaled them with the tale about agent Julian Bach’s misunderstood phone call about the $7,500 advance from Houghton Mifflin for The Water is Wide.

Pat told about his mother’s infinite influence on his career and how her ongoing encouragement had led him to become that “Southern writer” she had always wanted him to be. He said, “It is my mother’s voice that I speak in today. It is the power of her voice that moves me to write. My mother taught me what we all look for as writers. It is the moment when language and passion and the beauty of writing all come together.”

He told of his mother’s final bout with cancer that would ultimately take her life and of reading to her from her favorite books as she lay on her deathbed—just as she had read to him when he was a young boy.

Conroy’s speech had helped successfully launch his most important book to date, and sent booksellers home spreading the word about his book like new-born messengers who had just discovered religion. The Prince of Tides became the most talked about novel in America later that year and eventually spent 51 weeks on the New York Times Bestseller list.

Conroy is an author who has been privileged to have had three talented editors during his writing career. His arrival at Houghton Mifflin initially paired him with the respected Anne Barrett. Among her many lifetime accomplishments, she played a role in helping bring The Fellowship of the Ring to American audiences—which subsequently landed the J.R.R.Tolkien “mother lode” into Houghton’s lap.

Jonathan Galassi also served as Pat’s editor in the 1970s before he left and eventually succeeded Roger Straus as Publisher and Editor-in-Chief at Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Nan Talese became Pat’s editor upon Jonathan’s departure, and her style has worked well with Conroy ever since. Nan was offered her own signature “imprint” at Doubleday, and when she left Houghton, Conroy followed her to her new publishing home.

Pat had formed strong personal and professional ties with members of our publishing staff, and I remembered many of us having felt like jilted lovers the day he announced that he was leaving. Despite some futile attempts to make him rethink his decision, he was adamant that staying with his editor was the right thing to do. He explained that he had experienced an author’s dream of having had three sensational editors. He told me at the time, “My first editor retired and broke my heart; the second was so talented that he left to eventually run his own company, and this time I want to maintain some continuity with Nan Talese.”

His decision was based primarily on the strong and trusted symbiotic relationship that an author and editor often share. Nan has been one of the most respected editors in publishing for many years and has continued to produce books of literary excellence.

Pat Conroy summed up his writing life and career in rather dramatic fashion in his inspiring speech at that memorable Sunday morning breakfast in New Orleans :

“In those last few days of her life, my mother, Peg Conroy, the prettiest woman I had ever seen, was reduced to 80 pounds, and was suffering from vomiting and diarrhea.

She looked up from her bed and said to me, ‘Don’t make me like this. Promise to make me beautiful again.”

“From that moment on, I loved being a Southern writer.

I said, ‘Momma, I’m going to make you so beautiful.

And because you taught me how to be a writer,

I can lift you off that bed,

And I can set you singing,

I can set you dancing,

And I can make you beautiful again for everyone to see.”

The mood was broken abruptly when my mother interrupted,

“I’d like Meryl Streep to play the role!”

“Just before my mother slipped into a coma, my brothers and sisters sat around her bedside and read her poetry throughout the night. We sent her off that evening in a ‘wave of language,’ and it is that very ‘wave of language’ which brings us all here and binds us together. I’m here today because I love the language—and also because my mother wanted me to write it.”

*

Bob Vickrey is a freelance writer whose columns frequently appear in several Southwestern newspapers including the Houston Chronicle and the Ft. Worth Star-Telegram. He is a member of the Board of Contributors at the Waco Tribune-Herald. He lives in Pacific Palisades , California .