Edendale: Chapter 8

The Eighth Chapter of “Edendale,” Chicken Corner, by Phyl M. Noir

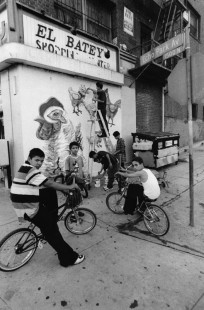

Photograph is by Gary Leonard, courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library

By Phyl M. Noir

The members of the dissertation committee at Columbia in New York City sat at a long table. Behind them was a tall window. Opaque light came through the window, and Celia imagined there was no outside but only a larger room encapsulating the smaller.

“I have some concerns,” the white woman professor complained. “One of my concerns is that you failed utterly to show the Marxist perspective in public housing activism during the 1930s.”

The clock on the wall clicked and new numbers slid into place next to the date. 9.30 a.m. May 14 1973.

“I hear you,” Celia said nodding. “My research shows no one had a Marxist perspective that supported public housing during the 1930s. American Marxists today have no interest in public housing. Richard Nixon and the real estate lobby in Los Angeles discredited socially owned housing during the Chavez Ravine farrago in 1952.”

“You reviewed, I should hope, the wealth of New York Times articles on the Unemployment Councils. I clearly advised you to review them and you appear not to have done so.” The professor said, thinking that Celia looked very like the Teddy Bear she had as a child and that her small tongue was so pink it looked as if it might be made of felt.

Celia had spent two weeks sitting at the microfilm machine in the central library reviewing articles on the Unemployment Councils. Statutes of two lions crouched at the entrance to the library. Inside, forest green glass shades on the lamps sat comfortingly on the mahogany tables. She had gone to the microfilm room and spooled every newspaper from the 1930s into a machine and read them on the screen.

“The Unemployment Councils, organized by the American Communist Party, did not advocate public housing. In my bibliography you will find my authorities included the Councils’ housing platform. The Communist Party called for reform of the mortgage industry to prevent foreclosures, and it called for legislation continuing rent control in New York City.” Celia said, her pink tongue shooting out with each word.

“The closest to a leftist position on any form of communally owned housing was reflected in the Jewish United Needle workers’ cooperative near Van Cortland Park in the Bronx and that was built with union, not government, financing. The New Deal sponsored utopian communities with cooperatively owned factories, but that’s a different story.”

Celia pointed out the passages in her dissertation on American economic philosophy with her brown forefinger. The members of the committee thumbed their copies of her work. Pages rustled. The clock clicked. If there is a hell, Celia thought, it would have a clicking clock.

The white woman’s face showed discomfort as she read the pages she should have read before coming into the room. “I see you made some effort but it’s inadequate and confusing.”

The Black professor spoke in a plum and chocolate voice. “It was a seamless web.” The woman professor imagined what she would look like if she were to writhe from her toes to the top of her head. Years of work, however, would go down the toilet unless he stayed on her side until she got tenure.

“You make a good point,” Celia responded as if he had made one. “Blacks had pressing legal problems: lynching, segregation, denial of the franchise and exclusion from unions among them. Black lawyers had so little influence they were excluded from membership in the American Bar Association.

“When Catherine Bauer lobbied for the Wagner-Steagall Act in Washington, D.C., a Southern Congressman informed her there were no slums to eradicate in the South. Bauer showed him photographs of shacks people wouldn’t put their chickens in. He said, “˜Why, honey, that’s just where the Nigras live.’

“A world of bigotry was in front of the Negroes in the 1930s. They didn’t have luxuries of time or wealth to argue for public housing. Middle class educated white people — so few, a member of the Labor Housing Conference joked, they could fit together in a telephone booth — urged public housing.”

“My point exactly,” the male professor mysteriously concurred.

“If you don’t see I must explain everything that led to the Act and then everything that led to public housing’s becoming relegated to housing the poorest one percent of the country, many of them people of color, then there’s no point in my being here.” Celia said.

She left them and walked out of the building into the street toward the stairs that led down to the subway tunnel. The tall buildings in New York cast shadows on the streets below them and Celia walked through the shadows. She had to look up to see the sky. She missed the real sky, the sky that was back home seen through the window of her old apartment in Chicken Corner in Los Angeles.

A white man in a suit stood on the corner next to a lamppost. Celia brushed against him. “Excuse me,” she said and he nodded.

A car pulled up next to the curb. Someone inside the car lowered the window on the passenger side of the front seat. The white man in the suit leaned towards the window as if responding to a question about directions. The car drove away.

The man staggered. He looked surprised, and he put his hands on his chest. Lilies of red blood flowed from him. A knife was stuck in his chest. He grabbed the lamppost and held himself upright by it.

She stood transfixed. It seemed to her that hours passed. Two white policemen ran towards her .

She joined the people descending the subway stairs, inserted her token in the slot and went through the turnstile. She went down the metal stairs and looked at her feet so she wouldn’t trip and saw the eyes of men standing under the stairs up-skirting through the holes in the metal steps.

Celia wore ankle-length dresses from Bloomingdale’s — bright floral prints made of rayon, pleated over her breasts ““ and platform shoes. The shoes made her four inches taller and looked like the shoes people who had had poliomyelitis as children wore on one foot to even their gait only she wore two of them. Hundreds of women sprained their ankles wearing platforms in New York City that year.

She boarded the Lexington Uptown to The Bronx, named after Jonas Bronck, an early settler from SmÃ¥land in Sweden whose land bordered the river on the east. After 1643, the Dutch displaced the Lenape people who had lived there for twenty-five thousand years. Celia’s people, today called the Tongva, came from Central Asia across the land bridge to Los Angeles 15,000 years ago.

The other trains smelled like children’s lunch boxes on a hot day; the Lexington smelled like coconut cookies. Two men talked at each over the roar of the trains. One yelled, “My prematurely graying pallet….” The other yelled back, “So I made myself a samich…”

The subway riders were all ugly. Some had gaping mouths. Some had bad complexions. An aging rhinoceros-skinned black giantess had upper arms dewlapped beyond belief. Her arms stuck out of her short sleeves, hanging as if dead.

The train rumbled through the charcoal tunnel: the dirty, confining and evil tunnel. She heard a sound like the creaking of an ironing board and thought they iron out our differences and then she thought something must have happened to her to think such a thing. Perhaps she was asleep.

She woke with a start. A red-eyed white man read a copy of the Daily News . He shook the paper violently and made it taut between his filthy hands. He pulled the paper to the left twice and down twice. “QUEEN ISABELLA!” He cried. “˜QUEEN ISABELLA DID THIS TO US!”

Celia admitted to herself that Isabella, Queen of Castile and Leon, had indeed done this to us. Isabella expelled the Muslims who had created the wonderful architecture and the Jews who made the jewelry and whose money financed the Empire. She paid for Christopher Columbus to discover a faster route to the Indies. At first, Isabella wanted the Indians — whom Columbus called La Gente en Dios — treated with respect but then changed her mind and allowed their enslavement ““ our enslavement, she thought, and with it the loss of what we should have taught the world.

A young woman rose from her seat in disgust and went into the next car and the door slid shut behind her. After she left, there was a mood of irritation and repulsion in the car as if phlegm covered the floor but it was only because of the tunnel, the dank Bronx tunnel.

Morning light ennobled the subway car as it emerged from the tunnel and daylight touched the worn faces with sweet rose color. The passengers stirred slightly. They no longer looked ugly.

A policeman walked through the car looking cruel under the fierce brim of his cap. He pushed it back and revealed a gentle young face.

The car ticked along the tracks around Yankee Stadium, around El-bordered brick apartments with photographs of Hong Kong movie stars and green walls or with plastic ivy surrounding portraits of flirtatious Puerto Rican women in low cut dresses. The car clicked past the hags hunting dimes and quarters from religious Jews near Yeshiva University. It passed vegetable stands containing Chinese cabbage, bok choy, bean sprouts, okra, dill weed and collard greens. The car passed the paper-littered corners and the bleak windows. Not far away, at the end of a strip of grass, stood the cottage of Edgar Allen Poe. He lived there when that part of the Bronx was wilderness over a hundred years earlier.

Celia got off the train. The trees in Van Cortland Park were in bloom. Blossomed boughs hung over the grass and paths. She walked to her apartment, which was really an entire floor in a house near the park.

Her landlords lived on the first floor. They were from one of the Baltic countries and drank vodka with no apparent effect when they ate pancakes with a Latvian name that means, “Come back tomorrow.” Sometimes, the pancakes contained zucchini, carrots and mushrooms that were roasted and added soft; other times they held cooked potatoes and cheese, and once in a while they were made of cottage cheese. Sour cream bound the ingredients.

The landlord’s daughter came out of the front door and stopped Celia from going upstairs. Celia hoped she was going to invite her to eat pancakes.

“I have an offer to work as a call girl,” she told Celia. “I’m not going to take it but you could. I could say I know someone. They’re looking for intelligent, educated women. They pay two thousand dollars a night.”

“I’m married,” Celia said.

“Your husband’s not much, is he? ”

Celia said, “No.”

The landlord’s daughter slammed the door to their floor.

Celia walked up the stairs into her apartment. It was empty except for a card table; two folding chairs, a bed, and a black and white television set and Champ, a Chihuahua. She fed Champ and took him for a walk and returned to the flat.

She took off her jacket and turned the television on and sat up in bed and turned on a program about Iceland. Champ shivered next to her.

The camera on the television program scanned fields of beautiful ice and green water. “Iceland,” the narrator said, “There are no Puerto Ricans there.”

Towards morning, she heard her husband downstairs bang on the front door. She went downstairs and opened the door.

He looked white as if held in a jar full of water for some hours. He said, “Is this the Woodlawn Station?”

“You’re home,” Celia told him.

“Is this the Woodlawn Station?” he said again.

“Yes.” She said.

He fell down. She helped him to his feet and pulled him upstairs and pushed him into bed.

Her husband took the dog in his hands and strangled him. Champ’s eyes bulged even bigger.

Celia removed Champ from her husband’s hands and comforted him. She went into the bathroom and took down the plastic shower curtain. She removed the towels.

She edged the plastic shower curtain under her husband and surrounded his head with towels. She went into the kitchen and took the jar of iced water from the refrigerator. She went back to the bedroom and turned her husband’s head and poured the ice water into his ear. She slid the shower curtain out from under his body and removed the towels. She hung the shower curtain back in the shower stall. She dried her husband’s head with the towels and then arranged the towels on the rack in the bathroom to dry.

She watched him sleep. He shouldn’t have married anyone. His mind was spoons of gold honey hidden within segments of waxy comb or red seeds spilling through their surround of fiber in a pomegranate. He didn’t look like Bruno but the insides of their minds were the same. Both men spun false personae to conceal their emptiness. She thought she attracted schizoid people ““ men and women because nothing else explained the woman with the German Shepherds — because schizoids came from families with schizophrenics. Her brother Malcolm was schizophrenic so the schizoids rushed to meet her because of genetic pull as strong as the moon and the tides and that she wore an invisible sign that read “I am one of you.”

When it was fully morning light came through the shades on the windows. Her husband woke with a start. He patted the pillows. He patted his ears. He looked first at Celia and then at Champ.

The next day she took a cab to her doctor across the County line in Yonkers.

In the late 1640s, Adriaen van der Donck received grant of land from the Dutch East India Company. His timber mill workers called van der Donck “Jonk Herr,” young gentleman. The area became “The Younckers.”

Her doctor’s waiting room was full of white people. Celia picked up a True Romance magazine from the coffee table in front of her couch. The cover promised a story: “I married a Negro And Had His Baby!”

The doctor was a white man with tired gray eyes behind bifocal lenses.

“I saw a man stabbed. I didn’t do anything. I just stood there. I couldn’t move.” Cyd said.

“You were in shock. You’re probably still in shock. You just need a little time to get over it. You shouldn’t feel bad.” He spoke Mid-Atlantic English that reflected both Dutch and Cockney phonologies.

“My husband strangled our Chihuahua. I have to look up between very tall buildings to see the sky.” She said in rhotic Californian.

She took a cab to the Woodlawn Station to Manhattan and sat in the subway car opposite and down from a white woman and her daughter. The daughter’s words had too many vowels. She pronounced “bottle” with a glottal stop. They said their names were Sally and Dot.

The car filled with young black boys, their Afros shining in the light like piles of tangled autumn weeds. They had inked the words “Black Devils” on their blue jeans. They sat next to Sally and Dot and the women got up and went through the door between the cars. The young men turned to Celia and stared at her.

How hard her life was. Only the year before she crossed the street and a car hit her when she was in the crosswalk and threw her fifteen feet. She saw herself as a stick figure thrown up in the air by a car and later knocked across the room by her husband. It was too much.

“Hey!” One of the Black Devils said. “She’s a-scared of us!”

She smiled at them — they weren’t much older than children.

One of the Devils got up and brought his face close to hers and stared unblinking into her eyes. The others laughed at her just as a middle aged black woman in a long Crayola-blue skirt and carrying a patent leather purse boarded the train. She wore a shiny rayon red blouse and had fastened a white carnation to it. At her neck was a pin like a cameo but modern. She looked like the American flag unfurling on a tall brown pole.

“What’s the matter with you!” The woman said to the Black Devils. They stood and offered her their seats. She ignored them and sat on another bench. They turned their heads back to Celia.

“I think she gonna cry-y-y.” Said a Black Devil.

“Hey brothers, leave her be,” sighed the woman.

The train reached Fordham Road. The Black Devils held the door open and looked at Celia.

“Off!” Ordered the woman.

Each one hit Celia on the head as he passed through the door. They didn’t hit hard.

“She’s embarrassed,” the woman said and crossed the aisle and sat next to Celia. “Don’t cry, Sister. They want to hit Johnson or Rocker-fellow and they can’t so they hit us.”

Celia laughed in surprise.

“That’s it. Laugh. They do it “˜cause you pretty and don’t be scared.”

“I wasn’t scared.”

“Sure you scared! We scared all the time.”

Celia nodded. She pointed to the pin on the woman’s red shirt. “Who’s that?”

“Why that’s Mao-Tse-Tung. He did a beautiful thing for his country. He’s a socialist! No hunger, no addiction, no filth anymore in his country.

“What we gotta do,” the woman continued, “is to have socialism in this country. Every neighborhood takes care of its own.” Her voice rose and fell as if she were singing in church. “Each day, I gotta educate myself not to want things — not to imprison myself with the goods and promises of capitalist society.”

“I don’t know that I could learn to live that way.”

“We have to, Sister! It’s all we got!”

Does a fish understand it’s wet? Does it wonder if it could learn to crawl out of water to reach air? Does it ask, “What is air?” Celia was like a fish in the ocean.

“We gotta kill everybody in power so they don’t come back, so they don’t make us slaves no more. This is where it ends, Sister — we got to be free!” She drew an American flag from her purse.

Kill? Celia thought. If she could kill she would kill her husband.

“You see this flag? It writes “˜MURDER’ on it, see? I’m going to a demonstration at the UN against the war. Our boys are dying in their war.”

“I know.”

“Take this,” the woman said and pulled a plastic bracelet of black, brown, and white beads from her wrist. “Remember: it’s all of us against those in power.” She took Celia’s hand in hers and slipped the bracelet on it.

Celia emerged from the subway station and her one thought was to reach the open air. Two women walked behind her. When they came up the stairs and into the fresh day one of them said, “Isn’t it a beautiful day?” and it seemed to Celia what she meant was, “Isn’t it life? Isn’t it love?” for it was a beautiful day.

A good-looking white man wearing an expensive pearl gray suit with a white linen shirt and who smelled of Aramis eau de toilette stopped her and asked if she wanted a date. She had read in the paper that prostitutes in New York were wearing eyeglasses and carrying books to look like students. She said, no, that she was married. She did not want to insult him by accusing him of looking for a prostitute although he probably was because why would he ask a stranger for a date.

The sympathy she once had for her husband was gone. They were enemies. She knew that he would be horribly injured if he left her because he was dependent on her and that meant he was going to come after her and kill her.

That evening Celia tied a bouncy ribbon around Champ’s neck and she put him in a baby blue plastic carrying case and boarded a plane from Kennedy Airport to Los Angeles.

A baby cried during the flight because the change in air pressure hurt his ears. Celia slept and dreamed she was in a subway under Los Angeles and that when she got off the subway she saw men with their shirtsleeves rolled up.

The plane flew over Los Angeles and Celia woke and looked through the window and saw illuminated lawns and swimming pools like blue candies in backyards. Car headlights moved along the dark streets. They circled and she saw the Elysian Park hills. The plane hit the runway and motored over to a terminal and Celia got up and went down the plane stairs.

The airline had lost her suitcase and in it was her underwear. She stood in front of the airport office and saw a casket covered with a flag loaded onto a conveyor belt. It disappeared into a cavity in the wall.

The dawn sun contracted cool shadows in the airport. She stood on the curb in a queue with Champ in his plastic case and a taxi stopped for her.

“Edendale,” she said.

They drove through burned-out streets.

“No one’s rebuilding after the riots,” the driver said.

He stopped at Chicken Corner but she saw the chicken seller wasn’t there anymore. She paid the taxi driver and got out of the cab.

A For Rent sign hung from the window of her old apartment. She rang the manager’s bell.

Ralph poked his head through the window of his apartment and saw Celia standing outside on the street.

“Celia!” Ralph said. “You came back.”

Celia saw the tender green leaves on the street trees. She smelled coffee and oil.

“My husband strangled Champ,” Celia said. “I saw a stabbed man and did nothing. I had to look up between tall buildings to see the sky in Manhattan. A car hit me. The members of my dissertation committee did not accept my dissertation. A crazy man knew about Queen Isabella. Black Devils hit me on the head. The airline lost my underwear. I saw a casket draped with a flag.”

“It’s okay,” Ralph said and took Champ out of the plastic case. “You’re young. I’m young. Start over. Start over again and again.” Champ trembled with joy in his arms.

Rent was cheap everywhere in Los Angeles and the poor still survived in the city’s interstices picking oranges and avocados hanging over backyard fences in Edendale’s alleys becoming movie stars and rock singers or caterers at banquets or runners for the movie studios or they moved out to the San Fernando Valley and bought houses with lawns in front and swimming pools in back for a song and rode horses dappled with sunlight like shining dimes on flesh as they passed through the shadows cast by eucalyptus trees.

Ralph found Celia a job as a warehouse worker in a collective that promoted organic fruits and vegetables organized by his friend Jade in the basement of an office building on Santa Monica Boulevard that was owned by Anarchists although one of the workers Cyd was a Marxist and the others called her The Marxist. The Marxist was a vegetarian and she sometimes drove the truck to the food co-ops and brought meat in an ice chest and said, “Here is your carcinogenic putrefaction.” When the Marxist saw the Angel of Death on a long drive through the Central Valley, the others in the collective agreed she could do something else so she drove the electric pallet jack until they had to make her stop because she was unintentionally knocking the warehouse walls down.

Jade kept the business records in file cabinets — all of them filed under M for miscellaneous — and she spent all day and most of the night in the basement. Nights she Celia and The Marxist carried a large defrosting fish from freezer to freezer because none of the freezers worked properly. By morning the warehouse floor was slimed with ice and workers from the food co-ops came through the door and slid on the floor and crashed into crates of brown rice and bottles of organic apple juice.

At the end of one night spent carrying the defrosting fish between them the women went outside to Santa Monica Boulevard and saw dawn break. A radio inside an office with a light on for the janitor played Louis Armstrong singing, “I see skies of blue “¦ clouds of white .. bright blessed days”¦dark sacred nights, and I think to myself what a wonderful world.” Armstrong sang it as if he wanted us to go outside and look around.

Above the women were the hoary heads of palm trees with bronze light behind them. Rats ran along telephone wires into the palm fronds.

The women linked arms and showed the soles of their shoes with each foot like the characters in one of the Robert Crumb cartoons and they said, “Keep on. Keep on. Keep on truckin’.”